by Brian Clegg

Getting to the Moon

As soon as it was realized that the Moon was more than a light in the sky, the idea of journeying to it became appealing, though early narratives of lunar travel now seem quaint in the extreme. Writers had no idea of the kind of distances involved. For that matter, they had no reason to think that air would not be readily available.

The earliest known example of a trip to the Moon stretches back 1900 years to Lucian of Samosata, a Roman living in Syria. His aim seems to have been to take a sneaky satirical poke at the Odyssey and other works of fantasy, presented as a kind of reality at the time. Lucian’s book True History was the equivalent of the Harvard Lampoon Tolkien parody, Bored of the Rings. Despite this, True History contains many features that would become prime themes of science fiction. After the first part of their journey, Lucian and his companions are lifted into the sky by a whirlwind which carries them to the surface of the Moon. Once there, the adventurers are caught up in a war between the kings of the Moon and the Sun over who should have the right to colonize Venus.

Image is in the public domain via Check this for reference

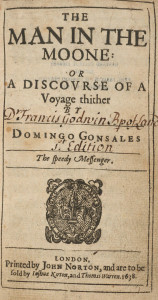

True History is unusual in surviving literature for the next 1500 years. But a whole list of fantastical journeys were made to the Moon in fiction from the seventeenth century onward. One of the first to write such a book was English bishop Francis Godwin who penned The Man in the Moone in the 1620s, though it wasn’t published until after his death in 1638. This was when Galileo was getting into trouble over his support for putting the Sun at the center of the universe. While Galileo was facing the Inquisition, Godwin wrote a story that went against the Aristotelian cosmology of the day. His Moon was very different from Aristotle’s perfect sphere: an inhabited world not unlike the Earth, with seas in the dark areas that we still give the name “mare” (sea in Latin). Godwin put the transport in the hand of gansas, an imaginary breed of swan that migrated to the Moon each year. On the other hand, he did describe the way his hero lost weight as he flew away from the Earth.

Image is in the public domain via Check this for reference

If hitching a ride with a flock of migrating birds seems unlikely, it is as nothing compared with Somnium, written by astronomer Johannes Kepler in 1634. In this, Kepler has his fictional hero cross a bridge of darkness, used by lunar demons to make the journey to Earth during eclipses. Despite this, Kepler too threw in some interesting thinking about the experience of being on the Moon. He realized that when looking back at the Earth he would see it in the lunar sky like a huge, dramatic moon. And, aware of the thinning of the atmosphere at high altitudes, he noted that the space travelers needed to have damp sponges pushed into their nostrils to breathe.

Surprisingly, though, the most scientific means of transport used to reach the Moon in this period came from Cyrano de Bergerac. We think of Cyrano as a fictional character because of the eponymous play from the end of the nineteenth century by French writer Edmond Rostand, but de Bergerac was a real seventeenth century playwright.

Image is in the public domain via Check this for reference

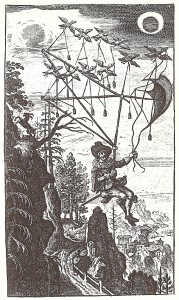

In his first person novel L’Autre Monde: ou les États et Empires de la Lune (The Other World: or the States and Empires of the Moon), Cyrano’s initial attempt at getting off the Earth involved flawed scientific thinking. He noted that the Sun made dew disappear, “drawing the fluid” off the surface. So, he surmised, a collection of bottles containing dew, attached to the astronaut with strings, should lift him into space. When the bottles didn’t work, a group of soldiers attached fireworks to Cyrano’s contraption, blasting him off using rocket power. Admittedly by luck, Cyrano had hit on the first vaguely realistic technological approach.

Plenty of other stories written over the next couple of centuries made use of the Moon as a backdrop to play with the possibilities of new social orders (or to mock existing ones), but the turning point from fantasy to science fiction was the arrival of the twin titans Jules Verne and H. G. Wells. Neither made use of realistic science in their respective books – but they brought the theme into the front rank of popular fiction. Within another 30 years, the science in space travel fiction was converging on reality.

Since our first true voyage to the Moon it has become a less popular destination in fiction. Yet that’s a shame. Every moonlit night we are presented with a reminder that we still haven’t truly conquered our nearest neighbor. The Moon has allure still as a destination for fiction and reality alike.

BRIAN CLEGG is the author of Ten Billion Tomorrows: How Science Fiction Technology Became Reality and Shapes the Future. He holds a physics degree from Cambridge and has written regular columns, features, and reviews for numerous magazines. He lives in Wiltshire, England, with his wife and two children.