By Stephen Dando-Collins

Down through the centuries, millions of men served with the army of imperial Rome; half a million during the reign of Augustus alone. The history of the legions is the collective story of those individuals, not just of Rome’s famous generals. Men such as Titus Flavius Virilis, still serving as a centurion at the age of 70. And Titus Calidius, a cavalry decurion who missed military life so much after retiring he re-enlisted, at the reduced rank of optio. And Novantius, the British auxiliary from today’s city of Leicester, who was granted his discharge thirteen years early for valiant service in the second century conquest of Dacia. Any analysis of the legions must begin with the men, their organization, their equipment, and their service conditions.

I. WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

The origins of the legions of Pompey, Caesar, Augustus, Vespasian, Trajan and Marcus Aurelius go back to the Roman Republic of the fifth century BC. Originally, there were just four Roman legions – Legios I to IIII (the legion number 4 was written as IIII, not IV). Each of the two consuls, ‘who were charged both singly and jointly to take care to preserve the Republic from danger’, commanded two of these legions. [Vege., III]

All legionaries were then property-owning citizens of Rome, conscripted in the spring of each year into the armies of the two consuls. Legio, the origin of the word ‘legion’, meant ‘levy’, or draft. Service ordinarily ended with the Festival of the October Horse on 19 October, which signalled the termination of the campaigning season.

Men of ‘military age’ – 16 to 46 – were selected by ballot for each legion, with the 1st Legion considered to be the most prestigious. Rome’s field army was bolstered by legions from allied Italian tribes. Legionaries of the early Republic were appointed to one of four divisions within their legion, based on age and property qualifications. The youngest men were assigned to the velites, the next oldest to the hastati, men in the prime of life to theprincipes and the oldest to the triarii, with the role and equipment of each group differing. By Julius Caesar’s day, the conscripted infantry soldier of the Republic was required to serve in the legions for up to sixteen years, and could be recalled in emergencies for a further four years.

Originally, republican legions had a strength of 4,200 men, which in times of special danger could be brought up to 5,000. [Poly., VI, 21] By 218 BC and the war between Rome and Carthage, the consuls’ legions consisted of 5,200 infantry and 300 cavalry, which approached the form they would take in imperial times. From 104 BC, the Roman army of the Republic underwent a major overhaul by the consuls Publius Rutilius Rufus and Gaius Marius. Rutilius introduced arms drill and reformed the process of appointment for senior officers. Marius simplified the requirements for enrolment, so that it was not only property owners who were required to serve. Failure to report for military service would result in the conscript being declared a deserter, a crime subject to the death penalty.

A legionary would be paid for the days he served – for many years, this amounted to ten asses a day. He was also entitled to the proceeds from any arms, equipment or clothing he stripped from the enemy dead, and was entitled to a share of the booty acquired by his legion. If a legion stormed a town, its legionaries received the proceeds from its contents – human and otherwise – which were sold to traders who trailed the legions. If a town surrendered, however, the Roman army’s commander could elect to spare it. Consequently, legionaries had no interest in encouraging besieged cities to surrender.

Marius focused on making the legions independent mobile units of heavy infantry. Supporting roles were left to allied forces. To increase mobility, Marius took most of the legionaries’ personal equipment off the huge baggage trains which until then had trailed the legions, and put it on the backs of the soldiers, greatly reducing the size of the baggage train. With the items hanging from their baggage poles weighing up to 100 pounds (45 kilos), legionaries of the era were nicknamed ‘Marius’ mules’. Until that time, the maniple of 160 – 200 men had been the principal tactical unit of the legion, but under Marius’ influence the 600-man cohort became the new tactical unit of the Roman army, so that the legion of the first century BC comprised ten cohorts, with a total of 6,000 men.

Half a century later, Julius Caesar fashioned his legions around his own personality and dynamic style. Of the twenty-eight legions of Augustus’ new standing army in 30 BC, some had been founded by Caesar, others moulded by him. The civil war, between the rebel Caesar and the forces of the republican Senate led by their commander Pompey the Great, created an insatiable demand for military manpower. At the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC, Caesar led elements of nine legions; Pompey, twelve. For the 42 BC Battle of Philippi, two years after Caesar’s murder, when Mark Antony, Marcus Lepidus and Octavian took on the so-called Liberators, Brutus and Cassius, more than forty legions were involved.

II. SOLDIERING FOR AUGUSTUS

The emperor Augustus, as Octavian became known from 27 BC, totally reformed the Roman army after he finally defeated Antony and Cleopatra in 30 BC.

In the professional army of Augustus, the legionary was a full-time soldier, sometimes a volunteer but more often a conscript, who signed on, initially for sixteen and later twenty years. Towards the end of his forty-three-year reign, Augustus was to boast: ‘The number of Roman citizens who bound themselves to me by military oath was about 500,000. Of these I settled in colonies or sent back into their own towns more than 300,000, and to all I assigned lands or gave money as a reward for military service.’ [Res Gest., I, 3] That retirement payment was standardized by Augustus at 12,000 sesterces for legionaries, 20,000 for men of the Praetorian Guard. After the completion of his enlistment, an imperial legionary could be recalled in an emergency to the Evocati, a militia of retired legionaries.

On Antony’s death, Augustus controlled approximately sixty legions. Many of these were promptly disbanded. ‘Others,’ said Cassius Dio, ‘were merged with various legions by Augustus’, and as a result ‘such legions have come to bear the name Gemina’, meaning ‘twin’. [Dio, LV, 23] By this process, Augustus created a standing army of 150,000 legionaries in twenty-eight legions, supported by 180,000 auxiliary infantry and cavalry, stationed throughout the empire. He also created a navy with two main battle fleets equipped with marines, and several smaller fleets. In addition, Augustus employed specialist troops at Rome – the elite Praetorian Guard, theCity Guard, the Vigiles or Night Watch, and the imperial bodyguard, the German Guard.

In AD 6, Augustus set up a military treasury in Rome, initially using his own funds, which were given in his name and that of Tiberius, his ultimate successor. To administer the military treasury he appointed three former praetors, allocating two secretaries to each. The ongoing shortfall in the military treasury’s funds was covered by a death duty of 5 per cent on all inheritances, except where the recipient was immediate family or demonstrably poor.

III. ENLISTING AND RETIRING

Some volunteers served in Rome’s imperial legions – ‘the needy and the homeless, who adopt by their own choice a soldier’s life’, according to Tacitus. [Tac., A, IV, 4] But most legionaries were conscripted. The selection criteria established by Augustus required men in their physical prime. A recruit’s civilian skills would be put to use by the legion, so that blacksmiths became armourers, and tailors and cobblers made and repaired legionaries’ uniforms and footwear. Unskilled recruits found themselves assigned to duties such as the surveyor’s party or the artillery. When it was time for battle, however, all took their places in the ranks.

A slave attempting to join the legions could expect to be executed if discovered, as happened in a case raised with the emperor Trajan by Pliny the Younger when he was governor of Bithynia-Pontus. Conversely, during the early part of Augustus’ reign it was not uncommon for free men to pose as slaves to avoid being drafted into the legions or the Praetorian Guard when the conquisitors, or recruitment officers, periodically did the rounds of the recruitment grounds. This became such a problem that Augustus’ stepson Tiberius was given the task of conducting an inquiry into slave barracks throughout Italy, whose owners were accepting bribes from free men to harbour them in the barracks when the conquisitors sought to fill their quotas. [Suet., III, 8]

Once Tiberius became emperor the task of filling empty places in the legions became even more difficult. Velleius Paterculus, who served under Tiberius, made a sycophantic yet revealing statement about legion recruitment in around AD 30: ‘As for the recruiting of the army, a thing ordinarily looked upon with great and constant dread, with what calm on the part of the people does he [Tiberius] provide for it, without any of the usual panic attending conscription!’ [Velle., II, CXXX] Tiberius, who followed Augustus’ policy of recruiting no legionaries in Italy south of the River Po, broadly extended the draft throughout the provinces.

Legionaries were not permitted to marry. Recruits who were married at the time of enrolment had their marriages annulled and had to wait until their enlistment expired to take a wife officially, although in practice there were many camp followers and many de facto relationships. The emperor Septimius Severus repealed the marriage regulation, so that from AD 197 serving legionaries could marry.

For many decades, each imperial legion had its own dedicated recruitment ground. The 3rd Gallica Legion, for example, was for many years recruited in Syria, despite its name, while both 7th legions were recruited in eastern Spain. By the second half of the first century, for the sake of expediency, recruiting grounds began to shift; the 20th Legion, for instance, which had up to that time been recruited in northern Italy, received an increasing number of its men from the East.

When a legion was initially raised, its enlistment took place en masse, which meant that a legion’s men who survived battle wounds and sickness were later discharged together. As a result, as Scottish historian Dr Ross Cowan has observed, Rome ‘had to replenish much of a legion’s strength at a single stroke’. [Cow., RL 58 – 69] When a legion’s discharge and re-enlistment fell due, all its recruits were enrolled at the same time. Although the official minimum age was 17, the average age of recruits tended to be around 20.

Some old hands stayed on with the legions after their discharge was due, and were often promoted to optio or centurion. There are numerous gravestone examples of soldiers who served well past their original twenty-year enlistment. Based on such gravestone evidence, many historians believe that all legionaries’ enlistments were universally extended from twenty to twenty-five years in the second half of the first century, although there is no firm evidence of this.

Legions rarely received replacements to fill declining ranks as the enlistments of their men neared the end of their twenty years. Tacitus records replacements being brought into legions on only two occasions, in AD 54 and AD 61, in both cases in exceptional circumstances. Accordingly, legions frequently operated well under optimum strength. [Ibid.]

By AD 218, mass discharges would be almost a thing of the past. The heavy losses suffered by the legions during the wars of Marcus Aurelius, Septimius Severus and Caracalla meant that the legions needed to be regularly brought up to strength again or they would have ceased to be effective fighting units. The short-lived emperor Macrinus (AD 217 – 218) deliberately staggered legion recruitment, for ‘he hoped that these new recruits, entering the army a few at a time, would refrain from rebellion’. [Dio, LXXIX, 30]

In 216 BC, two previous oaths of allegiance were combined into one, the ius iurandum, administered to legion recruits by their tribunes. From the reign of Augustus, initially on 1 January, later on 3 January, the men of every legion annually renewed the oath of allegiance at mass assemblies: ‘The soldiers swear that they will obey the emperor willingly and implicitly in all his commands, that they will never desert, and will always be ready to sacrifice their lives for the Roman Empire.’ [Vege., II]

On joining his legion, the legionary was exempt from taxes and was no longer subject to civil law. Once in the military, his life was governed by military law, which in many ways was more severe than the civil code.

IV. SPECIAL DUTIES

Legions’ headquarters staff included an adjutant, clerks and orderlies who were members of the legion. The latter, called benificiari, were excused normal legion duties and were frequently older men who had served their full enlistment but who had stayed on in the army.

V. DISCIPLINE AND PUNISHMENT

‘I want obedience and self-restraint from my soldiers just as much as courage in the face of the enemy.’

JULIUS CAESAR, The Gallic War, VII, 52

Tight discipline, unquestioning obedience and rigid training made the Roman legionary a formidable soldier. Roman military training aimed not only to teach men how to use their weapons, it quite deliberately set out to make legionaries physically and mentally tough fighting machines who would obey commands without hesitation.

As one of the indications of his rank, every centurion carried a vine stick, the forerunner of the swagger stick of some modern armies. Centurions were at liberty to use their sticks to thrash any legionary mercilessly for minor infringements. A centurion named Lucilius, who was killed in the AD 14 Pannonian mutiny, had a habit of brutally breaking a vine stick across the back of a legionary, then calling ‘Bring another!’, a phrase that became his nickname. [Tac., A, I, 23]

For more serious infringements, legionaries found guilty by a court martial conducted by the legion’s tribunes could be sentenced to death. Polybius described the crimes for which the death penalty was prescribed in 150 BC – stealing goods incamp, giving false evidence, homosexual offences committed by those in full manhood, and for lesser crimes where the offender had previously been punished for the same offence three times. The death penalty was later additionally prescribed for falling asleep while on sentry duty. Execution also awaited men who made a false report to their commanding officer about their courage in the field in order to gain a distinction, men who deserted their post in a covering force, and those who through fear threw away weapons on the battlefield. [Poly., VI, 37]

If whole units were involved in desertion or cowardice, they could be sentenced to decimation: literally, reduction by one tenth. Guilty legionaries had to draw lots. One in ten would die, with the other nine having to perform the execution. Decimation sentences were carried out with clubs or swords or by flogging, depending on the whim of the commanding officer. Survivors of a decimated unit could be put on barley rations and made to sleep outside the legion camp’s walls, where there was no protection against attack. Although both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony decimated their legions, this form of punishment was rarely applied during the imperial era.

First-century general Corbulo had one soldier brought out of the trench he was digging and executed on the spot for failing to wear a sword on duty. After this, Corbulo’s centurions reminded their men that they must be armed at all times, so one cheeky legionary went naked while digging, except for a dagger on his belt. Not famed for his sense of humour, Corbulo had this man, too, pulled out and put to death. [Tac., XI, 18]

VI. LEGIONARY PAY

Julius Caesar doubled the legionary’s basic pay from 450 to 900 sesterces a year, which was what an Augustan recruit could expect. This was increased to 1,200 by Domitian in AD 89. [Dio, LXVII, 3] Before this, Roman soldiers were paid 300 sesterces three times a year, instalments which Domitian raised to 400 sesterces each. [Ibid.]

The legionary’s annual salary was infinitesimal compared to the 100,000 sesterces a year earned by a primus pilus, the most senior centurion of a legion, and the 400,000 a year salary of the legate commanding the legion. Deductions were made from the legionary’s salary to cover certain expenses, including contributions to a funeral fund for each man. Conversely, he also received small allowances for items such as boot nails and salt.

Another source of legionary income was the donative, the bonus habitually paid to the legions by each new emperor when he took the throne – 300 sesterces per man was common. The legionaries normally received another, smaller, bonus on each subsequent anniversary of the emperor’s accession to the throne. In addition, emperors frequently left several thousand sesterces per man to their legionaries in their wills. Profits from war booty could also be substantial. After Titus completed the Siege of Jerusalem in AD 70, so much looted Jewish gold was traded in Syria that the price of gold in that province halved overnight.

A legionary could lodge his savings in a bank maintained at his permanent winter base; his standard-bearer was the unit’s banker. In AD 89, Domitian limited the amount each man could keep in his legion bank to 1,000 sesterces, after a rebel governor used funds from his legions’ banks in an abortive rebellion against him. [Suet., XII, 7]

A soldier who fought bravely could have his pay increased by 50 per cent or doubled for the rest of his career, and accordingly gained the titles of sesquipliciarus or duplicarius. Men with these awards were represented separately from the other rank and file when units submitted their strength reports to area headquarters, immediately following the optios and centurions on the lists. Men of duplicarius status proudly made reference to it on their tombstones.

To gain popularity with the legions, the emperor Caracalla (AD 211 – 217), ‘who was fond of spending money on the soldiers’, increased legionary pay and introduced various exemptions from duty for legionaries. [Dio, LXXVIII, 9] Cassius Dio, a senator at the time, complained that the salary increase would add 280 million sesterces to the cost of maintaining the legions. [Dio, LXXIX, 36] In AD 218, Caracalla’s successor Macrinus announced that the pay increase would only apply to serving legionaries and that new recruits would from that time forward be paid at the same rate as had applied during the reign of Caracalla’s father, Septimius Severus. This only hastened Macrinus’ overthrow that same year. [Ibid.]

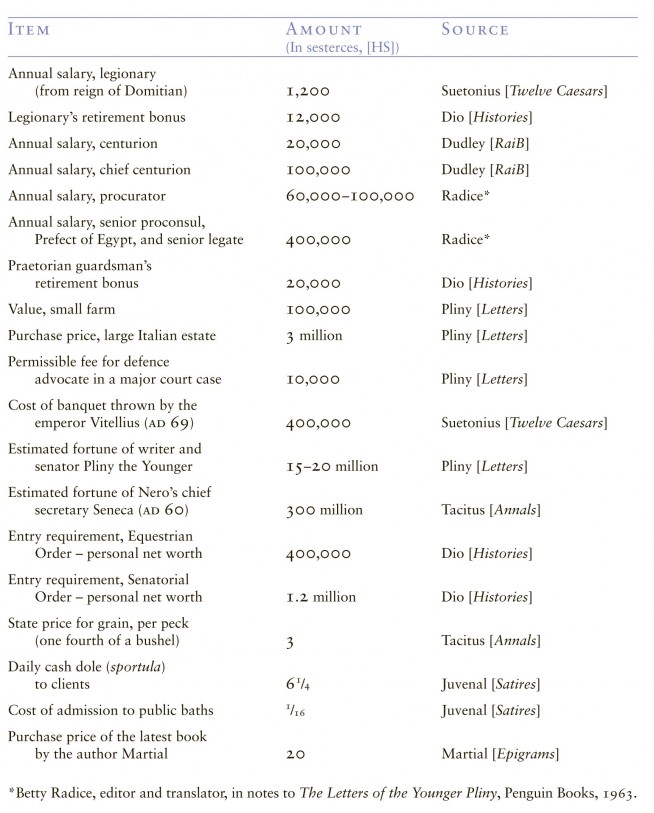

VII. COMPARATIVE BUYING POWER OF A LEGIONARY ‘S INCOME (First – Second Centuries AD)

VIII. MILITARY DECORATIONS AND AWARDS

Legionaries who distinguished themselves in battle could expect not only monetary rewards. At an assembly following a victorious battle, soldiers would be called forward by their general. A thorough written record was maintained on every man in every unit, with promotions, transfers, citations, reprimands and punishments all studiously noted down by the man’s optio, the second-in-command of his century. The general would read the legionary’s previous citations aloud, then praise the soldier publicly for his latest act of gallantry, promoting him and often giving him a lump sum cash award or putting him on double pay, before presenting him with decorations for valour, to the applause of the men of his legion. Polybius recorded these awards, which continued to be presented for hundreds of years: [Poly., VI, 39]

THE SPEAR: for wounding an enemy in a skirmish or other action where it was not necessary to engage in single combat and therefore expose himself to danger. Literally ‘the Ancient Unadorned Spear’, a silver, later golden, token. No award was made if the wound was inflicted in the course of a pitched battle, as the soldier was then acting under orders to expose himself to danger. The emperor Trajan appears to be presenting a spear to a soldier in a scene on Trajan’s Column.

THE SILVER CUP: for killing and stripping an enemy in a skirmish or other action where it was not necessary to engage in single combat. For the same deed, a cavalryman received a decoration to place on his horse’s harness.

THE SILVER STANDARD: for valour in battle. First awarded in the first century AD.

THE TORQUE AND AMULAE: for valour in battle. A golden necklace and wrist bracelets. Frequently won by centurions and cavalrymen.

THE GOLD CROWN: for outstanding bravery in battle.

THE MURAL CROWN: awarded to the first Roman soldier over an enemy city wall in an assault. Crenallated, and of gold.

THE NAVAL CROWN: for outstanding bravery in a sea battle. A golden crown decorated with ships’ beaks.

THE CROWN OF VALOUR: awarded to the first Roman soldier to cross the ramparts of an enemy camp in an assault.

THE CIVIC CROWN: awarded to the first man to scale an enemy wall. Made from oak leaves, the Civic Crown was also awarded for saving the life of a fellow soldier, or shielding him from danger. The man whose life was saved was required to present his saviour with a golden crown, and to honour him as if he were his father for the rest of his days. It was considered to be Rome’s highest military decoration, and the holder of the Civic Crown was venerated by Romans and given pride of place in civic parades. Julius Caesar was awarded the Civic Crown when serving as a young tribune in the assault on Mytilene, capital of the Greek island of Lesbos.

Entire units could also receive citations, and these were displayed on their standards.

IX. LEGIONARY UNIFORMS AND EQUIPMENT

In early republican days, each legionary was expected to provide his own uniform, equipment and personal weapons, and to replace them when they were worn out, damaged or lost. After the consul Marius’ reforms, the State provided uniforms, arms and equipment to conscripts.

The tunic and personal legionary equipment remained basically unchanged for hundreds of years. By Augustan times, the legionary wore a woollen tunic made of two pieces of cloth sewn together, with openings for the head and arms, and with short sleeves. It came to just above the knees at the front, a little lower at the back. The military tunic was shorter than that worn by civilians. In cold weather, it was not unusual for two tunics to be worn, one over the other. Sometimes more than two were worn – Augustus wore up to four tunics at a time in winter months. [Suet., II, 82]

With no examples surviving to the present day, the colour of the legionary tunic has always been hotly debated. Many historians believe that it was a red berry colour and that this was common to legions and guard units. Some authors argue that legionary tunics were white. Vitruvius, Rome’s chief architect during the early decades of the empire, wrote that, of all the natural colours used in dying fabrics and for painting, red and yellow were by far the easiest and cheapest to obtain. [Vitr., OA, VII, 1 – 2]

Second-century Roman general Arrian described the tunics worn by cavalry during exercises as predominantly a red berry colour, or, in some cases, an orange-brown colour – a product of red. He also described multicoloured cavalry exercise tunics. [Arrian, TH, 34] But no tunic described by Arrian was white or natural in colour. Red was also the colour of unit banners, and of legates’ ensigns and cloaks.

Tacitus, in describing Vitellius’ entry into Rome in July AD 69, noted that marching ahead of the standards in Vitellius’ procession were ‘the camp-prefects, the tribunes, and the highest-ranked centurions, in white robes’. [Tac., H, II, 89] These were the loose ceremonial robes worn by officers when they took part in religious processions. That Tacitus specifically notes they were white indicates that he was differentiating these garments from the non-white tunics worn by the military.

The one colour that legionaries and auxiliaries were least likely to wear was blue. This colour, not unnaturally, was associated by Romans with the sea. Pompey the Great’s son Sextus Pompeius believed he had a special association with Neptune, god of the sea, and in the 40s to 30s BC, when admiral of Rome’s fleets in the western Mediterranean, he wore a blue cloak to honour Neptune. After Sextus rebelled and was defeated by Marcus Agrippa’s fleets, Octavian granted Agrippa the right to use a blue banner. Apart from the men of the 30th Ulpia Legion, whose emblems related to Neptune, if any of Rome’s military wore blue in the imperial era, it would have been her sailors and/or marines.

Whatever the weather, and irrespective of the fact that auxiliaries in the Roman army, both infantry and cavalry, wore breeches, Roman legionaries did not begin wearing trousers, which were for centuries considered foreign, until the second century. Some scholars suggest that legionaries wore nothing beneath their tunics, others suggest they wore a form of loin cloth, which was common among civilians.

Over his tunic the legionary could wear a subarmalis, a sleeveless padded vest, and over that a cuirass – an armoured vest. Because of their body armour, legionaries were classified as ‘heavy infantry’. Early legionary armour took the form of a sleeveless leather jerkin on to which were sown small ringlets of iron mail. Legionaries and most auxiliaries continued to wear the mail cuirass for many centuries; there was no concept of superseding military hardware as there is today.

Early in the first century a new form of armour began to enter service, the lorica segmentata, made up of solid metal segments joined by bronze hinges and held together by leather straps, covering torso and shoulders. This segmented legionary armour was the forerunner of the armour worn by mounted knights in the Middle Ages. By AD 75, a simplified version of the segmented infantry armour was in widespread use. Called today the Newstead type, because an example was found in modern times at Newstead in Scotland, it stayed in service for the next 300 years.

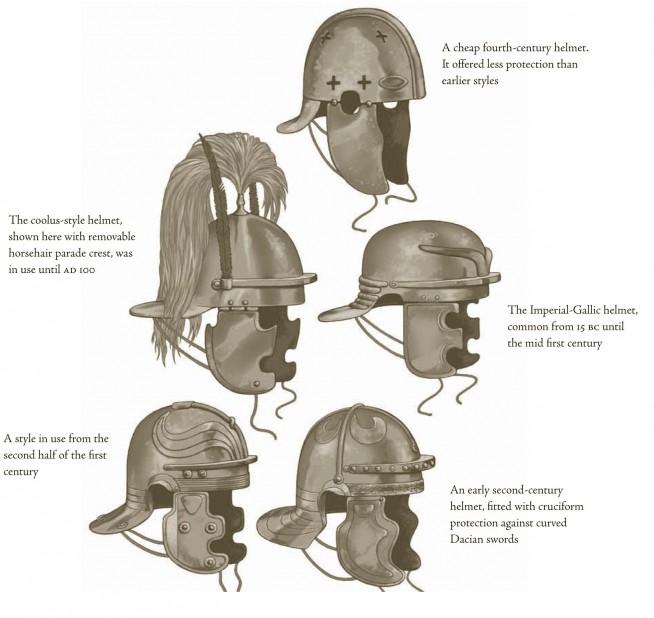

On his head, the legionary wore a conical helmet of bronze or iron. There were a number of variations on the evolving ‘jockey cap’ design, but most had the common features of hinged cheek flaps of metal, tied together under the chin, a horizontal projection at the rear to protect the back of the neck, like a fireman’s helmet, and a small brow ridge at the front.

First- and second-century legionary helmets unearthed in modern times have revealed occasional traces of felt inside, suggesting a lining. In the fourth century, the Roman officer Ammianus Marcellinus wrote of ‘the cap which one of us wore under his helmet’. This cap was probably made of felt, for Ammianus described how he and two rank and file soldiers with him used the cap ‘in the manner of a sponge’ to soak up water from a well to quench their thirst in the Mesopotamian desert. [Amm., XIX, 8, 8] By the end of the fourth century, legionaries were wearing ‘Pamonian leather caps’ beneath their helmets, which, said Vegetius, ‘were formerly introduced by the ancients to a different design’, indicating the caps beneath helmets had been in common use for a long time. [Vege., MIR, I0]

After a legion had been wiped out in AD 86 by the lethally efficient falx, the curved, double-handed Dacian sword, which had sliced through helmets of unfortunate Roman troops, legion helmets had cruciform reinforcing strips added over the crown to provide better protection. It was not uncommon for owners of helmets to inscribe their initials on the inside or on the cheek flap. A legionary helmet unearthed at Colchester in Britain had three sets of initials stamped inside it, indicating that helmets passed from owner to owner. [W&D, 4, n. 56] In Syria in AD 54, lax legionaries of the 6th Ferrata and 10th Fretensis legions sold their helmets while still in service. [Tac., A, XIII, 35]

During republican times, Rome’s heavy-armoured troops, the hastati, wore eagle feathers on their helmets to make themselves seem taller to their enemies. By the time of Julius Caesar, this had become a crest of horsehair on the top of legionary helmets. These crests were worn in battle until the early part of the first century, before being relegated to parade use. The colour of the crest is debatable. Some archaeological discoveries suggest they were dyed yellow. Arrian, governor of Cappadocia in the reignof Hadrian, described yellow helmet crests on the thousands of Roman cavalrymen under his command. [Arr., TH, 34] The feathers of the republican hastati were sometimes purple, sometimes black, which possibly evolved into purple or black legionary helmet crests. [Poly., VI, 23]

The helmet was the only item of equipment a legionary was permitted to remove while digging trenches and building fortifications. Helmets were slung around the neck while on the march. The legionary also wore a neck scarf, tied at the throat, originally to prevent his armour chafing his neck. The scarf became fashionable, with auxiliary units quickly adopting them, too. It is possible that different units used different coloured scarves. On his feet the legionary wore heavy-duty hobnailed leather sandals called caligulae, which left his toes exposed. At his waist he wore the cingulum, an apron of four to six metal strands which by the fourth century was no longer used.

X. THE LEGIONARY ‘S WEAPONS

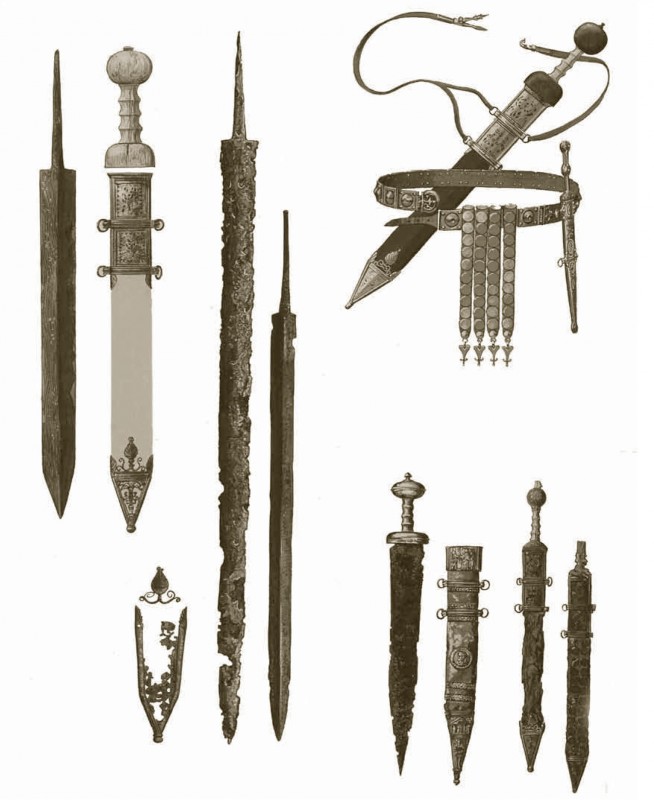

The imperial legionary’s first-use weapon was the javelin, the pilum, of which he would carry two or three, the shorter 5 feet (152 centimetres) in length, the longer, 7 feet (213 centimetres). Primarily thrown, javelins were weighted at the business end and, from Marius’ day, were designed to bend once they struck, to prevent the enemy from throwing them back. ‘At present they are seldom used by us,’ said Vegetius at the end of the fourth century, ‘but are the principal weapon of the barbarian heavy-armed foot.’ [Vege., MIR, I] By Vegetius’ day, a lighter spear, with less penetrating power, was used by Roman troops.

The legionary carried a short sword, the gladius, its blade 20 inches (50 centimetres) long, double-edged, and with a sharp point for effective jabbing. Spanish steel was preferred, leading to the gladius becoming known as ‘the Spanish sword’. It was kept in a scabbard, which was worn on the legionary’s right side, in contrast to officers, who wore it on the left.

By the fourth century, the gladius had been replaced by a longer sword similar to the spatha carried by auxiliary cavalry from Augustus’ time. The legionary was also equipped with a short dagger, the pugio, worn in a scabbard on the left hip, which was still being carried into the fifth century. Sword and dagger scabbards were frequently highly decorated with silver, gold, jet and ceramic inlay, even precious stones.

The legionary shield, the scutum, was curved and elongated. Polybius described the legionary shield as convex in shape, with straight sides, 4 feet (121 centimetres) long and 21/2 feet (75 centimetres) across. The thickness at the rim was a palm’s breadth. It consisted of two layers of wood fastened together with bull’s hide glue. The outer surface was covered with canvas and then with smooth calf-skin, glued in place. The edges of the shield were rimmed with iron strips, as a protection against sword blows and wear and tear. The centre of the shield was fixed with an iron or bronze boss, to which the handle was attached on the reverse side. The boss could deflect the blows of swords, javelins and stones. [Poly., VI, 23]

On to the leather surface of the shield was painted the emblem of the legion to which the owner belonged. Vegetius, writing at the end of the fourth century, said that ‘every cohort had its shields painted in a manner peculiar to itself’. [Vege., MIR, II] While Vegetius was talking in the past tense, several examples suggest that each cohort of the Praetorian Guard may have used different thunderbolt emblems on their shields. The shield was always carried on the left arm in battle, with a strap over the arm taking much of the weight. On the march, it was protected from the elements with a leather cover, and slung over the legionary’s left shoulder. By the third century, the legionary shield had become oval, and much less convex.

XI. LEGIONARY TRAINING

First-century Jewish general and historian Flavius Josephus described the training of Rome’s legions as bloodless battles, and their battles as bloody drills. ‘Every soldier is exercised every day,’ he said, ‘which is why they bear the fatigue of battles so easily.’ [Jos., JW, 3, 5, 1]

The legionary’s training officer was his optio, who ensured that his men trained and exercised. The Roman soldier’s sword training involved long hours at wooden posts. He was taught to thrust, not cut, using the sharp point of his sword. ‘A stab,’ said Vegetius, ‘although it penetrates just 2 inches [5 centimetres], is generally fatal.’ [Vege., MIR, I]

A legionary also learned to march in formation, and to deploy in various infantry manoeuvres. In standard battle formation soldiers would form up in ranks of eight men deep by ten wide, with a gap of 3 feet (1 metre) between each legionary, who, in the opening stage of a battle, would launch first his javelins then draw his sword. Withdrawing auxiliaries could pass through the gaps in the ranks, until, on command, the legionaries closed ranks. In close order, compacted against his nearest comrades, the legionary could link his shield with his neighbour’s for increased protection. His century might run to the attack, or steadily advance at the march.

In battle order, the century’s centurion was the first man on the left of the first rank. The century’s tesserarius was last on the left in the rear rank, while the optio stood at the extreme right in the rear rank, from where it was his task to keep the century in order and to prevent desertions. Basic battle formations included the straight line, oblique and crescent. For defence against cavalry, the wedge or a stationary hollow square would be employed, or a partial hollow square with the men on three sides facing outward while the tightly packed formation continued to shuffle forward. The orbis, or ring, was a formation of last resort for a surrounded force.

Apart from route marches, legionaries, from the time of the consul Marius, were also trained to run considerable distances carrying full equipment. In addition, the legionary learned defensive and offensive techniques, and to rally round his unit’s standard, or any standard in an emergency. The famous testudo, or tortoise, involved locked shields over heads and at sides, providing protection from a rain of spears, arrows, stones, etc. The testudo, ‘most often square but sometimes rounded or oblong’, was primarily used when legions were trying to undermine the walls of enemy fortresses, or to force a gate. [Arr., TH, 11] Double testudos are also known, with one group of men standing on the raised shields of a formation beneath them and in turn fixing their shields over their own heads.

XII. LEGIONARY RATIONS AND DIET

Cassius Dio wrote of the diet of legionaries: ‘They require kneaded bread and wine and oil.’ [Dio, LXII, 5] Legionaries were given a grain ration, which they were expected to grind into flour using each squad’s grinding stone. They cooked their own loaves, typically round and cut into eight slices, one for each member of the squad. Legionaries drizzled their bread with olive oil. They also ate meat, but thiswas considered supplementary to their bread ration. Coffee, tomatoes and bananas were unknown to the Romans, as was sugar; honey was their only sweetener.

The quantity of grain provided for the troops depended on the available supply and the generosity of commanders. In Polybius’ day it was half a bushel per legionary a month, and the cost was deducted from the soldier’s pay. In imperial times, the legionary’s grain ration was free. Much of the general population of Rome at that time was also provided with free grain by the government, although bakers, pastrycooks, and other commercial operators had to pay for it.

Like the upper class, Roman soldiers ate with their fingers. They used their dagger to cut bread and meat. The fork was unknown to all classes. Romans drank wine with their meals, but it was diluted with water; legionaries are rarely recorded drunk in camp. Breakfast for Romans was often just a cup of water. Lunch, prandium, was a cold snack at noon, or a piece of bread at the end of the day’s march. For legionaries, the day’s main meal was in the evening.

By late in the first century, with legions based in permanent winter camps, rations were being acquired from local merchants who themselves sourced food and wine from the far corners of the empire. Some of those foods could be quite exotic, and both legionaries and auxiliaries ate well. Parts of the handwritten labels on amphorae have been found on pottery shards discovered in a fort which housed the cavalry of the Ala Augusta at Carlisle, Roman Luguvalium, in Britain. One had contained the sweet fruit of the doum palm from Egypt. Another reads: ‘Old Tangiers tunny, provisions, quality, excellent, top-quality.’ Tunny fish (cordula) netted in the Straits of Hercules (off Gibraltar) was processed at Tingatitanum, today’s Tangiers, being chopped up and packed in its own juice into amphora for shipment. The resultant fish paste was a great delicacy; at the Carlisle base it was probably exclusively consumed by officers. [Tom., DRA]

Amphorae containing provisions were also marked with the age of the contents in years, the capacity of the container, and the name of the firm that had produced it – a label found at Colchester named the firm of Proculus and Urbicus. Another label from the very same firm was also found in the ruins of Pompeii in Italy. [Ibid.]

XIII. FURLOUGHS AND FURLOUGH FEES

During the first century, and probably for much of the imperial era, when a legion went into winter quarters each year one legionary in four could take leave. The job of recording leave details fell to each unit’s records clerk, who was ‘exact in entering the time and limitation of furloughs’. [Vege., DRM, III] To receive their leave pass, the enlisted men of each legion had to pay their centurion a furlough fee, which the centurions retained.

Until AD 69, centurions could set the fee at any amount they chose, and this became a source of great complaint from legionaries. Tacitus wrote, ‘A demand was then made [to new emperor Otho] that fees for furloughs usually paid to the centurions be abolished. These were paid by the common soldiers as a kind of annual tribute. A fourth part of every century could be scattered on furlough, or even loiter about the camp, provided they paid the fees to the centurions.’ The officers had not given any attention to these fees, said Tacitus, and the more money a soldier had, the more his centurion would demand to allow him to go on leave. [Tac., H, I, 46]

Otho did not want to alienate the centurions by abolishing furlough fees, a lucrative source of income for them, but at the same time wanted to ensure the loyalty of the enlisted men. So he promised in future to pay to centurions the furlough fees on all legionaries’ behalf from his own purse. [Ibid.] Within months, Otho was dead, but his successor as emperor, Vitellius, kept his promise to the rank and file: ‘He paid the furlough fees to the centurions from the imperial treasury.’ [Tac., H, I, 58] ‘This was without doubt a salutary reform,’ Tacitus observed, ‘and was afterwards under good emperors established as a permanent rule of the service.’ [Ibid., 46]

Men on furlough often went far afield, and could not easily be recalled in emergencies. [Tac., A, XV, 10] It seems that while the men left their helmets, shields, javelins and armour back at base when they went on furlough, they habitually continued to wear their military sandals and travelled armed with their swords on sword-belts wherever they went, even in towns, where civilians were forbidden to go armed. Petronius Arbiter, in hisSatyricon, written in the time of Nero, has his narrator strap on a sword-belt when staying in a seaside town in Greece. While walking through the town’s streets at night, illegally wearing his sword, he was challenged.

‘Halt! Who goes there?’ a guard demanded. Seeing the sword on his hip, the guard assumed the man must be a legionary on leave, and asked, ‘What legion are you from? Who is your centurion?’ The guard then noticed that the man waswearing Greek-style white shoes. ‘Since when have men in your unit gone on leave in white shoes?’ In response, Petronius’ narrator lied about both centurion and legion. ‘But my face and my confusion proved that I had been caught in a lie,’ he went on, ‘so he [the guard] ordered me to surrender my arms.’ [Petr., 82]

XIV. LEGION MUSICIANS

To relay orders in camp, on the march, and in battle, unarmed musicians were attached to all legions to play the lituus, a trumpet made of wood covered with leather, and the cornu and buccina, which were horns in the shape of a ‘C’. Legion musicians wore leather vests over their tunics, and bearskin capes over their helmets. There is no record of them playing music on the march. Their role was exclusively that of signallers.

XV. THE STANDARD-BEARER , TESSERARIUS AND OPTIO

Every legion, maniple and century had a standard behind which its men marched, and it was a great honour to be the official bearer of the sacred standard. It was the greatest honour of all to be the aquilifer, the man who carried the legion’s golden eagle standard, the aquila. Ranking above ordinary legionaries, the standard-bearer had much influence with the rank and file and was sometimes involved in councils of war by their generals. Standard-bearers also managed the legion banks.

The tesserarius was the man in each century whose task it was to circulate the tessera, a wax tablet containing the daily watchword, to sentries in camp, and to all ranks prior to battle.

In the infantry, the optio was the deputy to a century’s centurion. In the cavalry, he was deputy to a decurion. The equivalent of a sergeant-major today, the optio was responsible for the century’s records and training, and in battle was required to keep his century in order – several trumpet calls were directed specifically at optios for this purpose. An optio was a centurion-designate, and when a vacancy arose for a new centurion, an optio would be promoted to fill it.

XVI. THE DECURION

With his title literally and originally relating to the command of ten men, the decurio was a junior officer, subordinate to a centurion, who commanded a troop of cavalry in both the legions and auxiliary mounted units, which in turn was commanded by a squadron’s most senior decurion. Typically, decurions of auxiliary cavalry had previously served as legionaries and were transferred to the alae.

A second-century decurion, Titus Calidius, joined a legion at the age of 24 and rose to become a decurion with the cavalry squadron of the 15th Apollinaris Legion. He was subsequently transferred, as a senior decurion, to the 1st Alpinorum Cohort,an auxiliary equitata unit based at Carnuntum with the 15 th Apollinaris during the reign of Domitian. When Calidius completed his enlistment with the 1st Alpinorum he re-enlisted with the unit, which continued to be based at Carnuntum after the 15th Apollinaris Legion was transferred to the East in AD 113 for Trajan’s Parthian War. Calidius went back to the 1st Alpinorum Cohort at the reduced rank of optio of horse. He died at the age of 58, having served in the Roman military for thirty-four years, and was buried at Carnuntum. [Hold., DRA, ADRH]

XVII. THE CENTURION

The centurio was the key, middle-ranking officer of the Roman army. Julius Caesar considered the centurion the backbone of his army, and knew many of his centurions by name. Apart from some centurions of Equestrian rank during the reign of Augustus, the imperial centurion was an enlisted man like the legionary, promoted from the ranks. One centurion of Equestrian rank was Clivius Priscus, a native of Carecina in Italy, who ended his military career as a first-rank centurion. His son Helvidius Priscus, born around AD 20, became a quaestor, legion commander and praetor.

The centurion originally commanded a century of one hundred men. Centurions commanded the centuries, maniples and cohorts of the legion, with each imperial legion having a nominal complement of fifty-nine centurions, across a number of grades. Julius Caesar’s reward for one particular centurion who had pleased him was to promote him eight grades. The centurion could be identified – by friend and foe alike – by a transverse crest on his helmet, metal greaves on his shins, and the fact that, like all Roman officers, he wore his sword on the left, unlike legionaries, who wore their swords on the right.

The first-rank centurions, or primi ordines, of a legion’s 1st cohort, were the most senior in the legion. Promotion came with time and experience, but many centurions never made it to first-rank status. One first-rank centurion in each legion held the title of primus pilus – literally ‘first spear’. He was chief centurion of the legion, a highly prestigious and well-paid position for which there was always intense competition among centurions. The vastly experienced primi pili always received great respect and significant responsibility, not infrequently leading major army detachments.

Promotion up the various centurion grades involved transfer between various legions. One centurion typically served with twelve different legions during his forty-six-year career throughout the empire. Centurions were also detached from legions to serve as district officers in areas where no legions were based, and were also sent to other legions and auxiliary units as training officers. In AD 83, after a centurion and several legionaries were sent to train a new cohort of Usipi German auxiliaries in Britain, the trainees rebelled, killed their trainers, stole ships and sailed to Europe. The mutineers were subsequently apprehended.

Slaves were not permitted to become legionaries, let alone centurions. In AD 93, time-served centurion Claudius Pacatus was living in retirement when he was recognized as a slave who had escaped many years before. Because of Pacatus’ distinguished military service, the emperor Domitian spared his life, but he returned him to his original master, to live out the rest of his days as a slave.

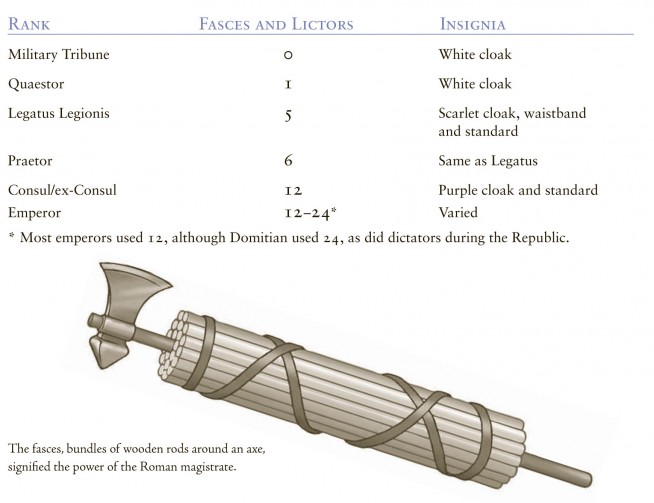

On their retirement, centurions were eligible for employment as lictors, the attendants of magistrates. This well-paid and prestigious post, renewed annually, involved walking ahead of the officials, and clearing the way, carrying one of their ceremonial fasces, the magistrates’ rods and axes of office.

Many centurions had long careers. Titus Flavius Virilis, a centurion with the 9th Hispana Legion, served for forty-five years before he died at Lambaesis in Africa early in the second century while on attachment to the 3rd Augusta Legion; he was 70 years of age. [ILS, 2653]

XVIII. THE CAMP-PREFECT

The third-in-command of each legion of the early empire was the praefectus cas-trorium, or camp-prefect. A mature former primus pilus, the camp-prefect was the legion’s quartermaster, and commanded major legion detachments. On occasion – inVarus’ army in the Battle of the Teutoburg in AD 9, and in the case of the 2nd Augusta Legion in Britain in AD 60, for example – camp-prefects commanded entire legions.

By the end of the fourth century, the camp-prefect had been abolished, being replaced by a junior tribune.

XIX. THE TRIBUNES

Young men of Equestrian rank ‘served as military tribune as a stepping stone to the Senate’, said Dio. [Dio, LXVII, 11] In the republican Roman army, a legion’s six tribunes had commanded the troops in battle – each one, on rotation, commanding the legion, the other five commanding two cohorts each. But over time this proved unsatisfactory, and in Augustus’ remodelled Roman army the command structure changed dramatically.

Each imperial legion still had six tribunes – one broad-stripe tribune or military tribune, five thin-stripe tribunes (the titles referring to the width of the purple stripes on their togas, and possibly also on their tunics). But the tribunes’ roles had altered.

From 23 BC, every well-to-do young Equestrian had to serve as a tribunus angus-ticlavius, tribune of the thin stripe. According to Seneca, the chief secretary to Nero, a thin-stripe tribune did ‘his military service as the first step on the road to a seat in the Senate’. [Sen., XLVII] The thin-stripe tribune was an officer cadet, serving a six-month military apprenticeship, the semestri tribunata, during the annual campaigning season from March to October. Once they turned 18, thin-stripe tribunes became eligible for the semestri tribunata and – provided their assets totalled the qualifying sum of 400,000 sesterces net – were granted membership of the Equestrian Order.

Gnaeus Agricola, for example, when he went to Britain as a thin-striper in AD 60, was 19. Most thin-stripe tribunes served on the staff of a legate, a legion commander. But some thin-stripers, like Agricola, were taken on to the staff of provincial governors, where they had more opportunity to shine. Appointment as a thin-striper under a legate of note, whose commendation would help later career prospects, did not come about by chance. Examples exist of senators writing to legion commander friends and provincial governors, putting forward their relatives or the sons of friends for appointment as thin-stripe tribunes. [Birl., DRA¸ TCEO]

Legates often took their own sons with them to the provinces to serve on their staff, apparently submitting lists of names of young men they would like to accompany them, or to fill vacancies in their province, for the emperor’s approval.

The legion in which Romans served out their semestri tribunata was never listed on memorials or in biographies when the careers of men of achievement were later recorded. It was, after all, nothing more than an internship. Conscientious thin-stripers wishing to make an impression on their sponsors and earn commendation would volunteer for special duty. Historian Tacitus’ father-in-law Agricola did not waste his time on the staff of the governor of Britain as a ‘loose young’ thin-stripe tribune enjoying a ‘life of gaiety’. Said Tacitus, Agricola did not ‘make his thin-stripe status or his inexperience an excuse for idly enjoying himself and continually going on leave’. Instead, ‘he acquainted himself with his province and made himself known to the troops. He learned from the experts and chose the best models to follow. He never sought a duty for self-advertisement, and never shirked one through cowardice. ‘ [Tac., Agr., 5] This suggests that many teenage thin-stripe tribunes wasted their semestri tribunata appointments living it up, leading the ‘life of gaiety’ that Agricola eschewed.

Thin-stripe tribunes had no authority. When Varus’ legions were wiped out at the Battle of the Teutoburg in AD 9, the units’ most senior officers were their camp-prefects. [Velle., II, CXX] The three legions involved all had junior tribunes serving with them, and these young men were burned to death by the Germans after their capture. [Tac.,A, I, 61] Apart from staff duties, thin-stripe tribunes could sit on court martials and shared watch command duties in camp, but in battle they held no power of command.

The sixth tribune in each imperial legion was the tribunus laticlavius, tribune of the broad stripe. Called a military tribune in official Roman records, to differentiate this position from the civil post of tribune of the plebeians, a broad-stripe tribune was second-in-command of his legion. Senior tribunes wore a richly decorated helmet, moulded armour and wore a white cloak. They were armed with a sword, worn on the left hip.

Broad-stripers frequently found themselves leading their unit. Some legions, such as those stationed in Egypt, and also in Judea for a time, were permanently commanded by their senior tribunes. This was because those provinces were governed by prefects, and as the legion commanders in their provinces had to take orders from the governors, they could not outrank them. There are numerous examples of legionselsewhere being led on the march and into battle by their broad-stripe tribunes.

To be promoted to the broad-stripe tribunate, an Equestrian officer had to serve out the first two steps of the three-step promotional ladder formalized by the emperor Claudius (AD 41 – 54), first as a prefect of auxiliary infantry, then as a more prestigious prefect of auxiliary cavalry, then as a broad-stripe tribune. [Suet., V, 25] A broad-stripe tribune was not yet a senator, but his appointment to the tribunate put him on the list for promotion to the senatorial order at the emperor’s pleasure. Broad-stripe tribunes usually served with a legion for three to five years, with passage through the entire three-step promotional process frequently taking nine or ten years, although an outstanding senatorial candidate could be appointed to the Senate at the age of 25.

Claudius realized that, with just twenty-seven legions in his day, there were only twenty-seven military tribunates to fill every three years or so, limiting the number of annual vacancies. With the military tribunate becoming a promotional bottleneck, Claudius introduced the annual appointment of supernumerary military tribunes, to push larger numbers of qualified young men through to the Senate. [Ibid.] These supernumerary tribunes did not serve with the legions, but were found other duties. In AD 68 – 69, Agricola fell into this category, serving out his military tribunate in Italy raising recruits. By AD 71 he had been promoted to a legion command.

Occasionally, broad-stripe tribunes of the early empire went from being second-in-command of legions to being in command of auxiliary cavalry units, an apparently backward step. These seem to have been special battlefield appointments, such as that of Gaius Minicius, who was transferred from the 6th Victrix Legion to command of the 1st Wing of the Singularian Horse in AD 70 during the Civilis Revolt. [See here.]

Promotion to legion command was neither automatic nor necessarily swift. The future emperor Hadrian, while he was building his military career between AD 95 and 105, spent ten years as a prefect and tribune, commanding various auxiliary units and then being promoted to second-in-command of a legion, the 5th Macedonica, before gaining command of the 1st Minervia Legion.

In around AD 85, Pliny the Younger served as a tribune with the 3rd Gallica Legion at Raphanaea on the Euphrates in southern Syria, where, on the orders of the province’s governor, he conducted an audit of the accounts of the cavalry and infantry cohorts attached to his legion (in several cases finding, ‘a great deal of shocking rapacity and deliberate inaccuracy’). [Pliny, VII, 31]

By the second half of the second century, military tribunes were increasingly appointed to the command of auxiliary units, probably because of the growing number of supernumerary tribune appointments. For instance, Pertinax, a future emperor, served as a tribune of cavalry on his way to becoming a successful general. [Dio, LXXIV, 3]

XX. THE PREFECT

After his junior tribuneship, a young Equestrian officer gained the rank of prefect and was appointed to command an auxiliary cohort – either an infantry unit or an equitatae unit which combined infantry and cavalry. After serving for several years, he would be transferred to the command of an equitatae unit or cavalry wing. He still held the rank of prefect, but a prefect of a mounted unit outranked an infantry prefect. A promising candidate could eventually be appointed a tribune of the broad stripe.

XXI. THE QUAESTOR

Every consul and every provincial governor had a quaestor appointed to his staff; Mark Antony initially served as quaestor to Julius Caesar during the Gallic War. The quaestor was a former broad-stripe tribune. In the provinces, a quaestor’s responsibilities included military recruitment in his province. He automatically entered the Senate on completion of his term as quaestor.

A junior magistrate, the quaestor was entitled to one fasces and one lictor. The fasces represented the magistrate’s power over life and death. Its symbol was an axehead projecting from a bundle of elm or birch rods tied with a red strap. Rods of birch were used to beat a condemned man; the axe was then used to behead him.

In 1919, the Fascist Party of Italy took the ancient Roman fasces as its symbol, a word from which the fascist name derived. Benito Mussolini’s Italian fascists adopted other imperial Roman symbols such as the eagle and military standards, hoping that some of the old glory would rub off. The fascist name, the eagle and the standards were in turn appropriated by Hitler’s National Socialist Party in Germany, the Nazis.

XXII. THE LEGATE

In Augustus’ military reforms, the legion commander was the legatus legionis, or legate of the legion. A member of the Senatorial order, he was typically in his thirties. The oldest legion legate on record is 62-year-old Manlius Valens, commander of the 1st Italica Legion in AD 68 – 69; his appointment was the result of a political favour from the emperor Galba.

Augustus set the maximum tour of duty of a legionary legate at two years. Under later emperors this stretched to an average four-year appointment. Tiberius was infamous for leaving men in appointments long term once he had found a place for them, and under him service was longer than usual.

The legate could be distinguished by his richly decorated helmet and body armour, his embroidered scarlet cloak, the paludamentum, and his cincticulus, a scarlet waistband tied in a bow at his waist. He was entitled to five fasces and five lictors.

By AD 268, the emperor Gallienus had decreed that senators could no longer hold legion commands, and by the end of the third century all legions were being commanded by Equestrian prefects, who then outranked tribunes. [Amm., v, 33]

XXIII. THE PRAETOR

The praetor was a senior Roman magistrate. From the middle of the first century, former praetors were increasingly given legion commands. Outranking legion legates, they were entitled to six fasces and lictors. Both Vespasian and his brother Sabinus held praetor rank when they commanded legions in the AD 43 invasion of Britain.

After AD 268, under the decree of Galienus, praetors no longer held commands.

Propraetor was the title given to governors of imperial Roman provinces – as opposed to proconsul, the title given to ‘unarmed’ senatorial provinces, whose governors were appointed by the Senate.

XXIV. SENIOR OFFICER RANK DISTINCTIONS

Early Imperial Roman Army

XXV. SENIOR OFFICERS OF THE LATE EMPIRE

Prefects, dukes and counts take command

During the reign of co-emperor Diocletian (AD 285 – 305), Rome’s original provinces were divided into more than a hundred smaller provinces, each with their own governor and military commander. Between AD 312 and 337 Constantine the Great took this reorganization further.

With prefects commanding legions, senior tribunes continued to be second-in-command of legions, on the emperor’s direct appointment. A ‘second tribune’ replaced the old enlisted rank of camp-prefect as third-in-command of a legion, and was given the appointment on merit after lengthy service. [Vege., II]

Thin-stripe tribunes were replaced as officer cadets by the candidati militares, the military candidates. Under Constantine, this officer training corps comprised two cohorts attached to the emperor’s bodyguard. Wearing white tunics and cloaks, candidatores, as they were called, were all young men chosen for their height and good looks. Candidati service prepared suitable trainee officers for promotion to tribune and unit commands. On several occasions in the fourth century, the candidates militares went into battle with their emperors, serving as independent fighting units within the imperial bodyguard.

The fourth-century provincial governor was a civilian. Separate provincial military commanders held the rank ofdux, or ‘leader’, the latter-day duke. The duke’s superior was a regional commander whose authority might extend across several provinces, or even in some cases the entire east or west of the empire, holding the rank of comes, literally meaning ‘companion’ of the emperor, the latter-day count. Counts also had charge of areas of civil administration. Military comites also commanded the household guard. In the late fourth century there were always two military counts and thirteen dukes in the west of the Roman Empire, while in the east there were four military counts and twelve dukes.

Both duke and count were distinguished when in armour by a golden cincticulus, the general’s waistband, as opposed to the scarlet cincticulus of legion legates of old. The duke and count received generous salaries as well as allowances that provided each with 190 personal servants and 158 personal horses. In place of the two praetorian prefects, Constantine introduced the posts of master ofinfantry and master of horse as the empire’s supreme military commanders. The post of praetorian prefect was retained, but in a civil administrative role, with several stationed throughout the empire as financial auditors reporting directly to their emperor. [Gibb., XVII]

Many fourth- and fifth-century Roman commanders had foreign blood, among them the counts Silvanus and Lutto, both Franks; Magnentius, a German; Ursicinus, who was probably an Alemanni German; and Stilicho, one of whose parents was a Vandal. The father of Count Bragatio, Master of Horse under Constantius II, was a Frank. Mallobaudes, who was a tribune with the armaturae, a heavy-armoured element of the Roman household cavalry in the fourth century, was a Frank by birth, and went on to become king of the Franks. Victor, Master of Horse under the emperor Valens, was a Sarmatian.

XXVI. AUXILIARIES

The auxiliary was a foreign soldier who did not originally hold Roman citizenship. Most provinces and a number of allied states supplied men to fill auxiliary units of the Roman army. Some auxiliary units lived and fought alongside particular legions; others operated independently. In the AD 60s, for example, eight cohorts of Batavian light infantry were partnered with the 14th Gemina Legion.

At least two wings of auxiliary cavalry would also march with a specific legion, so that a legion, with its auxiliary support, would typically take the field with around 5,200 legionaries and a similar number of auxiliaries, creating a fighting force of 10,000 men. In the first century, it was assumed that a legion would always march with its regular auxiliary support units – Tacitus, referring to reinforcements received by Domitius Corbulo in the East in AD 54, described the arrival of ‘a legion from Germany with its auxiliary cavalry and light infantry’. [Tac., A, XIII, 35]

Independent auxiliary units provided the only military presence in so-called ‘unarmed’ provinces – Mauretania in North Africa, for instance, was for many years only garrisoned by auxiliaries.

Although often armed in a similar manner to legionaries, auxiliaries wore breeches, sported light ringmail armour, and were referred to as ‘light infantry’. Specialist units such as archers, and slingers firing stones and lead shot, were always auxiliaries. Syria provided the best bowmen, while Crete and Spain’s Balearic Isles were famous for their slingers. Each legion had a small cavalry component of 128 men, as scouts and couriers, but auxiliaries made up all the Roman army’s independent cavalry units. Germans, and in particular Batavians, were the most valued cavalry.

The auxiliary was paid just one third of the salary of the legionary; 300 sesterces a year until the reign of Commodus, when it increased to 400 sesterces. [Starr, V. I] The auxiliary also served for longer – twenty-five years, as opposed to the legionary’s sixteen- and later twenty-year enlistment (plus Evocati service). Once discharged, auxiliaries could not be recalled. They did not receive a retirement bonus, but both auxiliaries and seamen received an enlistment bonus, the viaticum, on joining the service, of 300 sesterces. [Ibid.]

From Britain to Switzerland, and from the Balkans to North Africa, tribes were responsible for supplying recruits for their particular ethnic auxiliary units, although there were occasional exceptions. Tiberius decreed that new recruits to the Thracian Horse would come from outside Thrace, much to the aggravation of the proud men of the existing Thracian Horse.

Copies of every individual patent of citizenship issued to discharged auxiliary soldiers were kept at the Capitoline Hill complex at Rome in the Temple of the Good Faith of the Roman People to its Friends. The auxiliary prized his certificate of citizenship; some had themselves depicted on their tombstones holding it. In AD 212, Commodus made Roman citizenship universal, eliminating citizenship as an incentive for auxiliary service.

A typical auxiliary who served his twenty-five years and gained his citizenship was Gemellus from Pannonia, who joined up in AD 97 during the reign of Nerva, and was granted his citizenship on 17 July AD 122 in the reign of Hadrian. Just as a legionary could be transferred between the legions with promotion, auxiliaries moved between different units. When Gemellus received his honourable discharge, he was a decurion with the 1st Pannonian Cohort. His career had seen him work his way from 7th cohort to 1st, serving in units from the Balkans, France, Holland, Spain, Switzerland and Greece, including a stint with the 7th Thracian Cohort in Britain.

Even after they obtained their citizenship, auxiliaries frequently signed up for a new enlistment. Lucius Vitellius Tancinus, a cavalry trooper of the Vettonian Wing, born at Caurium in Spain, joined the army at the age of 20, served his twenty-five-year enlistment in Britain, obtained his citizenship, then signed on for another term. A year later, at the age of 46, he died, probably seeking a cure for whatever ailed him at the Temple of Aquae Sulis in Bath, the waters of which had legendary healing powers.

During most of the imperial era, auxiliary units were commanded by prefects, always members of the Equestrian Order, and frequently young gentlemen of Rome. But in some cases, auxiliary units were commanded by nobles from their own tribe. These ethnic prefects were rarely permitted to rise above prefect rank.

A BRITISH AUXILIARY EARNS EARLY RETIREMENT

The reward for brave service for Rome

On 10 August AD 110, Novanticus, a foot soldier born and raised in the town of Ratae, modern-day Leicester in England, was standing at assembly in a Roman army camp at Darnithethis in recently conquered Dacia. Novanticus was a Celtic Briton. He and some 1,000 other young Celts had joined the Roman army in the spring of AD 98, enrolled by the recently enthroned emperor Trajan in a new auxiliary light infantry unit honoured with the emperor’s family name: the Cohors I Brittonum Ulpia, or 1st Brittonum Ulpian Cohort.

Three years later, the 1st Brittonum had been one of many units in the 100,000 -man Roman army that had invaded Dacia. Novanticus and his British comrades had fought so fiercely and so bravely in the bitterly contested battles in the mountains and passes of Dacia, that, four years after the country had been conquered, the emperor granted all the surviving members of the unit honourable discharges, thirteen years before their twenty-five-year enlistments were due to expire.

At assembly, Novanticus presented himself before his commanding officer and was handed a set of bronze sheets just large enough to fit in one hand. This was the Briton’s discharge certificate, a copy of which would go to Rome to be displayed with hundreds of thousands of others. With discharge, Novanticus received the prize of Roman citizenship. With citizenship, he could take a multipart Roman name. Novanticus chose a name that honoured the emperor he had loyally served for the past twelve years.

‘To the foot soldier Marcus Ulpius Novanticus, son of Adcobrovatus, of Ratae,’ the commander read, ‘for loyal and faithful service in the Dacian campaigns, before the completion of military service.’ [Discharge certificate of Marcus Ulpius Novanticus, British Museum]

Marcus Ulpius Novanticus would return home to Britain to enjoy the fruits of his military service and raise a family. Nearly 2,000 years later, his bronze discharge certificate would emerge from the British earth to tell of his part in the Roman war machine.

XXVII. THE USE OF MULTIPART NAMES BY ROMAN AUXILIARIES AND SAILORS

Until AD 212, when Caracalla introduced universal Roman citizenship, auxiliaries, marines and seamen in the Roman navy were not Roman citizens. Non-citizens, so-called peregrines, traditionally only used a single name – Genialus, for example. A Latin multipart name such as Gaius Julius Genialus was the preserve of those with the Latin franchise. Accordingly, students of Roman history, from the famous nineteenth-century German scholar Theodor Mommsen onwards, came to assume that anyone recorded with a multipart name had to be a Roman citizen. But, as Professor Chester Starr and others point out, non-citizens serving in the Roman military not infrequently used Latin names, and consequently the legal status of a Roman soldier or sailor cannot always be ascertained from their name. [Starr, V. I]

Among other examples, Starr, quoting three other eminent scholars, cites the cases of Isidorus and Neon, two non-citizen Egyptian recruits to the 1st Cohort Lusitanorum Praetoria who immediately changed their names to Julius Martialis and Lucius Julius Apollinaris on enrolling. Octavius Valens, an Alexandrine recruit to the same unit, could not have possessed Latin rights either, despite using a Latin name. [Ibid.]

Claudius attempted to stamp out this practice, forbidding peregrines to adopt Roman family names. But under later emperors the practice revived, and, as Starr notes, auxiliaries came to take on Latin names ‘at their pleasure’. [Ibid.] Until the reign of Nero, auxiliaries recruited into the German Guard (the imperial bodyguard) took Greek or Latin names, or cobbled Latin names to their native names on joining. [Speid., 4] During Nero’s reign, numerous serving members of the German Guard bore tri-part names which included their native name and ‘Tiberius Claudius’. [Ibid.] This was in honour of Nero’s predecessor Claudius, in whose reign these men would have joined the unit.

In the reign of Trajan, auxiliary troopers of the Augustan Singularian Horse, the household cavalry, routinely added the names Marcus Ulpius to their own immediately on joining. This would always mark them as men who served the emperor. Likewise, in the reign of Hadrian, when recruits joined this same unit, many took the names of that emperor, Publius Aelius. [Ibid.]

By the second century, the practice of non-citizens using multi-part Latin names was not only commonplace but was accepted at the highest levels, as is made clear by a c. AD 106 letter of Pliny the Younger to Trajan, in which he wrote, ‘I pray you further to grant full Roman citizenship to Lucius Satrius Abascantus, Publius Caesius Phosphorus and Pancharia Soteris’. [Pliny, X, II]

Latin names were in extensive use by men serving in second-century auxiliary units despite the fact they had yet to gain Roman citizenship. This is plain to see in an AD 117 report from the 1st Lusitanorum Cohort in Egypt. The report details the receipt of new recruits from the province of Asia and their distribution to various centuries within this auxiliary cohort. The names of the standard-bearers of those auxiliary centuries are all either double- or triple-barrelled. [Tom., DRA]

The few surviving records of complete careers of centurions and decurions who served in auxiliary units reveal that those men were Roman citizens, having started out as legionaries before being promoted and transferred to auxiliary units. Yet a ration report from the cavalry wing stationed at Luguvalium in Britain, in the late first or early second century, refers to most of the decurions who commanded the sixteen troops of cavalry at the fort by single name. But all these were nicknames, among them: Agilis (Nimble), Docilis (Docile), Gentilis (Kinsman), Mansuetus (Gentle), Martialis (Warlike), Peculiaris (Special Friend), and Sollemnis (Solemn).

An example of a peregrine who adopted a multipart Latin name as soon as he joined the Roman navy is second-century Egyptian seaman Apion, who wrote hometo his family in Egypt to tell them that he had arrived safely at the fleet base at Misenum on Italy’s west coast and joined the crew of the warship Athenonike. Almost as an aside, he finished his letter with, ‘My name is now Antonius Maximus’. [Starr, V, I]

XXVIII. NUMERI

From the second century, units made up of foreign troops called numeri – literally ‘numbers’ – served with the Roman army as frontier guards, supplied by northern neighbours including the Sarmatians and Germans. Numeri was a generic title for a unit that was not of standard size or structure. No information exists about them. More than twenty numeri units served in Britain alone. [Hold., RAB, Indices]

XXIX. MARINES AND SAILORS

Marines served with the two principal Roman battle fleets, at Misenum near Naples, and at Ravenna on the northeast coast, on the Adriatic, as well as with the lesser fleets around the empire. Marine cohorts also acted as firefighters at major ports such as Ostia and Misenum.

Always non-citizens, and frequently former slaves, marines and sailors were considered inferior to both the legionary and the auxiliary. The marine, the miles classicus, was paid less than the legionary and served longer, for twenty-six years. Seamen operating the oars and sails of Rome’s warships served under identical conditions to marines, and also received weapons training, to allow them to repel boarders and to act as boarders. Both marines and seamen were organized into centuries, under centurions, aboard their vessels. A libernium, the smallest Roman war galley, typically had a crew of 160 seamen and forty marines.

Marines were trained to operate catapults that fired burning missiles from their ships. They were also involved in close-quarters combat, throwing javelins at enemy ships alongside, often from elevated wooden towers erected on deck. And they formed boarding parties to take enemy ships.

Excerpted from Legions of Rome: The Definitive History of Every Imperial Roman Legion by Stephen Dando-Collins.

Copyright © 2010 by Stephen Dando-Collins.

Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

STEPHEN DANDO-COLLINS is an award-winning historian and novelist. He is the author of several highly acclaimed works on ancient history, including Legions of Rome: The Definitive History of Every Imperial Roman Legion.