by Adam Nicolson

Chapter 1

One evening ten years ago I started to read Homer in English. With an old friend, George Fairhurst, I had just sailed from Falmouth to Baltimore in southwest Ireland, 250 miles across the Celtic Sea. We had set off three days earlier in our wooden ketch, the Auk, forty-two feet from stem to stern, a vessel which had felt big enough in Falmouth, not so big out in the Atlantic.

It had been a ruinous journey. A mile or so out from the shelter of Falmouth we realized our instruments were broken, but we had been preparing for too long, were hungry to go, and neither of us felt like turning back. A big storm came through that night, force 8 gusting 9 to 10, west of Scilly, and we sailed by the stars when it was clear, by the compass in the storm, four hours on, four hours off, for that night, the next day and the following night. The seas at times had been huge, the whole of the bow plunging into them, burying the bowsprit up to its socket, solid water coming over the foredeck and driving back toward the wheel, so that the side-decks were like mill-sluices, running with the Atlantic.

After forty hours we arrived. George’s face looked as if he had been in a fight, flushed and bruised, his eyes sunk and hollow in it. We dropped anchor in the middle of Baltimore harbor, it’s still water reflecting the quayside lights, only our small wake disturbing them, and I slept for sixteen hours straight. Now, the following evening, I was lying in my bunk, the Auk tied up alongside the Irish quay, with the Odyssey, translated by the great American poet-scholar Robert Fagles, in my hand.

I had never understood Homer as a boy. At school his poems were taught to us in Greek, as if they were a branch of math. The master drew the symbols on the green chalkboard, and we ferreted out the sense line by line, picking bones from fish. The archaic nature of Homer’s vocabulary, the pattern of long and short syllables in the verse, the remote and uninteresting nature of the gods, like someone else’s lunchtime account of a dream from the night before—what was that to any of us? Where was the life in it? How could this remoteness compare to the urgent realities of our own lives, our own lusts and anxieties? The difficulties and strangeness of the Greek were little more than a prison of obscurity to me, happily abandoned once the exam was done. Homer stayed irrelevant.

Now I had Fagles’s words in front of me. Half idly, I had brought his translation of the Odyssey with me on the Auk, as something I thought I might look at on my own sailing journey in the North Atlantic. But as I read, a man in the middle of his life, I suddenly saw that this is not a poem about then and there, but now and here. The poem describes the inner geography of those who hear it. Every aspect of it is grand metaphor. Odysseus is not sailing on the Mediterranean but through the fears and desires of a man’s life. The gods are not distant creators but elements within us: their careless pitilessness, their flaky and transient interests, their indifference, their casual selfishness, their deceit, their earth-shaking footfalls.

I read Fagles that evening, and again as we sailed up the west coast of Ireland. I began to see Homer as a guide to life, even as a kind of scripture. The sea in the Odyssey is out to kill you—at one point Hermes, the presiding genius of Odysseus’s life, says, “Who would want to cross the unspeakable vastness of the sea? There are not even any cities there”—but hidden within it are all kinds of delicious islands, filled with undreamed-of delights, lovely girls and beautiful fruits, beautiful landscapes where you don’t have to work, fantasy lands, each in their different way seducing and threatening the man who chances on them. But everyone is bad for him. Calypso, a goddess, unbelievably beautiful, makes him sleep with her night after night, for seven years; Circe feeds him delicious dinners for a whole year, until finally one of his men asks him what he thinks he is doing. If he goes on like this, none of them will ever see their homes again. And is that what he wants?

In part I saw the Odyssey as the story of a man who is sailing through his own death: the sea is deathly, the islands are deathly, he visits Hades at the very center of the poem and he is thought dead by the people who love him at home, a pile of white bones rotting on some distant shore. He longs for life, and yet he cannot find it. When he hears stories told of his own past, he cannot bear it, wraps his head in his “sea-blue” cloak and weeps for everything he has lost.

Image is in the public domain via Wikimedia.org

It was Odysseus I fell in love with that summer as we sailed north to the Hebrides, Orkney and the Faroes: the many-wayed, flickering, crafty man, “the man of twists and turns,” as Fagles calls him, translating the Greek word polytropos, the man driven off course, the man who suffers many pains, the man who is heartsick on the open sea. His life itself is a twisting, and maybe, I thought, that is his destiny: he can never emerge into the plain calm of a resolution. The islands in his journey are his own failings. Home, Ithaca, is the longed-for moment when those failings will at last be overcome. Odysseus’s muddle is his beauty.

He is no victim. He suffers, but he does not buckle. His virtue is his elasticity, his rubber vigor. If he is pushed, he bends, but he bends back, and that half-giving strength was to me a beautiful model for a man. He is all navigation, subtlety, invention, dodging the rocks, storytelling, cheating and survival. He can be resolute, fierce and destructive when need be, and clever, funny and loving when need be. There is no requirement to choose between these qualities; Odysseus makes them all available.

Like Shakespeare and the Bible, we all know his stories in advance, but one in particular struck me that summer sailing on the Auk. We had left the Arans late the evening before, and George had taken her all night up the dark of the Galway coast. We changed places at dawn, and in that early morning, with a cup of tea in my hand and the sun rising over the Irish mainland, I took her north, heading for the Inishkeas and the corner of County Mayo, before turning there and making for Scotland.

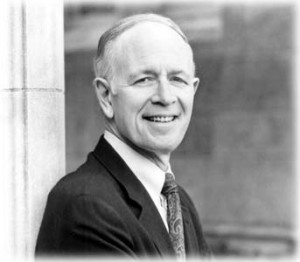

Adam Nicolson is the author of Why Homer Matters and the New York Times bestseller God’s Secretaries, Sea Room, Sissinghurst, and Seamanship. Among his honors are the Somerset Maugham Award, the W. H. Heinemann Prize, and the British Topography Prize; he lives on a farm in Sussex with his wife and their five grown children.