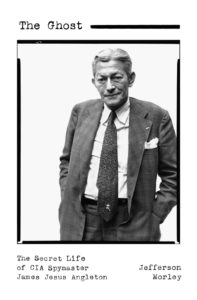

by Jefferson Morley

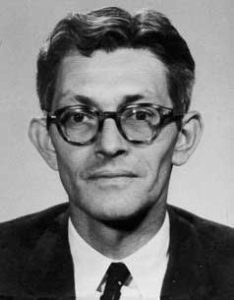

CIA spymaster James Angleton was one of the most powerful unelected officials in the United States government in the mid-20th century, a ghost of American power. From World War II to the Cold War, Angleton operated beyond the view of the public, Congress, and even the president. He unwittingly shared intelligence secrets with Soviet spy Kim Philby, a member of the notorious Cambridge spy ring. He launched mass surveillance by opening the mail of hundreds of thousands of Americans. He abetted a scheme to aid Israel’s own nuclear efforts, disregarding U.S. security. He committed perjury and obstructed the JFK assassination investigation. He oversaw a massive spying operation on the antiwar and black nationalist movements and he initiated an obsessive search for communist moles that nearly destroyed the Agency.

In The Ghost, investigative reporter Jefferson Morley tells Angleton’s dramatic story, from his friendship with the poet Ezra Pound through the underground gay milieu of mid-century Washington to the Kennedy assassination to the Watergate scandal. Read on for an excerpt of this revelatory new biography of the sinister, powerful, and paranoid man who was at the heart of the CIA for more than 30-years.

In The Ghost, investigative reporter Jefferson Morley tells Angleton’s dramatic story, from his friendship with the poet Ezra Pound through the underground gay milieu of mid-century Washington to the Kennedy assassination to the Watergate scandal. Read on for an excerpt of this revelatory new biography of the sinister, powerful, and paranoid man who was at the heart of the CIA for more than 30-years.

Secretary

THE HIDEOUS CRACK OF the missile blast jolted the floorboards, shattered the windows, buffeted the typewriters, and drove glass into every cranny of the cramped room at 14 Ryder Street in central London. Not long after, Angleton arrived for work at the OSS headquarters. It was raining hard and a brisk gale blew through the jagged panes as he went up to the second-floor office. Many nights, he slept on a cot by the desk. Luckily, Angleton had spent the previous night elsewhere, a twist of fate that might have saved his life.

It was March 1944. Angleton had gone through OSS training school in Bletchley Park, where he was reunited with Norman Pearson, who was responsible for the X-2 indoctrination training of the American arrivals. “X-2” served as shorthand for counterintelligence. Pearson also called on a British colleague, Harold Philby, an SIS section chief known to all as Kim, to explain the workings of a wartime intelligence station.

After completing his training, Angleton was assigned to the Ryder Street office. The city was under siege from long-range German rockets fired from Flanders across the English Channel. Every day and night, V-2 missiles slammed into apartment blocks, office buildings, pubs, churches, and schools around the city, killing randomly and terrorizing generally.

Angleton’s secretary, Perdita Macpherson, found him stamping around the drafty, shattered office in his overcoat. Angleton swept the glass off his chair and sat down to work.

JIM ANGLETON LEARNED THE craft of counterintelligence from two masters: Norman Pearson and Kim Philby.

Pearson was the more intellectual of two. Now living in England, he liked nothing more than to spend his Sundays sipping tea in the flat of his friend Hilda Doolittle, the poet known as H.D. The rest of the week, he taught the subtle arts of counterintelligence, defined as “information gathered and activities conducted to protect against espionage, sabotage or assassinations conducted for or on behalf of foreign powers, organizations, or persons.” Angleton would prove to be his most brilliant student.

Kim Philby was more of a rising civil servant. He had grown up in a well-to-do and well-traveled family. His father, Harry St. John Philby, had parlayed his livelihood as an Anglo-Indian tea planter into a career as a confidant to the royal family of Saudi Arabia. His son, Kim, was educated at Cambridge and dabbled in journalism before joining the Secret Service in 1940. From the start Philby distinguished himself from his more conventional colleagues with a casual wardrobe, incisive memoranda, and a mastery of Soviet intelligence operations in Spain and Portugal. He taught Angleton how to run double-agent operations, to intercept wireless and mail messages, and to feed false information to the enemy. Angleton would prove to be his most trusting friend.

Angleton had found a calling and a mentor.

Once he met Philby the world of intelligence that had once interested him consumed him. “He had taken on the Nazis and the Fascists head-on and penetrated their operations in Spain and Germany,” he said. “His sophistication and experience appealed to us. . . . Kim taught me a great deal.”

SO DID NORMAN PEARSON. He imparted to Angleton his knowledge about one of the most significant activities housed at Bletchley Park: ULTRA, the code-breaking operation that enabled the British to decipher all of Germany’s military communications and read them in real time. By May 1944, the British believed they had, for perhaps for the first time in modern military history, a complete understanding of the enemy’s intelligence resources.

Pearson also sat on the committee that decided how to use the ULTRA information. He was let in on another, even more closely held British secret: the practice of “doubling” certain German agents to feed disinformation back to Berlin so as to shape the thinking and the actions of Hitler’s generals.

It was a subtle, dirty game that Pearson shared with Angleton. The Germans had infiltrated dozens of spies into England with the mission of stealing information, identifying targets, and reporting back to listening posts on the Continent. When the British captured one of the German spies, they would “double” him—that is, compel him to send back a judicious mixture of false and accurate data, which would give the Germans a mistaken view of battlefield reality. In the run-up to the Normandy invasion of June 1944, the British had manipulated the Germans into massing their troops away from the selected landing point. The deception enabled the Allied armies to land at Normandy and start their drive toward Paris with the German resistance in disarray.

Angleton was learning how deception operations could shape the battlefield of powerful nations at war.

JEFFERSON MORLEY is a journalist and editor who has worked in Washington journalism for over thirty years, fifteen of which were spent as an editor and reporter at The Washington Post. The author of Our Man in Mexico, a biography of the CIA’s Mexico City station chief Winston Scott, Morley has written about intelligence, military, and political subjects for Salon, The Atlantic, and The Intercept, among others. He is the editor of JFK Facts, a blog. He lives in Washington, DC.