by Dr. Vincent DiMaio and Ron Franscell

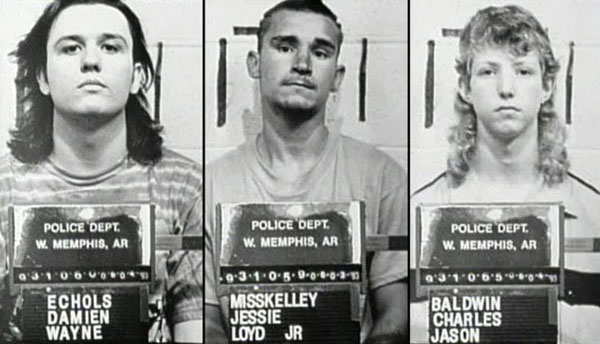

The West Memphis Three

In 1996, HBO aired a documentary called Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills. It made a vivid case that the three oddball teenagers (The West Memphis Three) had been wrongly convicted by shoddy police work in a small town gripped by “Satanic panic,” in farcical trials by country-bumpkin jurors. The film convinced many people, especially some vocal celebrities. Soon a website was launched, then sequels, and more celebrity voices. Some pointed at a different possible killer.

Then a 2003 book, Devils Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three, by Mara Leveritt, also argued that the 1994 trials were gravely flawed. (Later, a 2012 documentary financed by Oscar-winning director Peter Jackson and directed by Amy Berg, West of Memphis, added new fuel to the long- smoldering fire.)

Things got worse for the authorities when, in 2003, the waitress who claimed she’d attended an esbat with Misskelley and Echols admitted she lied.

What began as an indie-film exploration of a sensational murder case blossomed into a full-fledged movement to free the West Memphis Three. Celebrities such as actor Johnny Depp, Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder, pop philosopher Henry Rollins, and the Dixie Chicks’ Natalie Maines, among others, lent their voices, money, and moral support. High- dollar defense lawyers and legal experts galore also came to the party.

In time, even Chris Byers’s father and Stevie Branch’s mother were convinced the West Memphis Three had been wrongly accused. Then in 2007, a bombshell revelation: Preliminary tests indicated DNA found at the crime scene didn’t match Echols, Baldwin, or Misskelley—but a hair found in a knot that bound one of the boys was declared “not inconsistent with” hair from Terry Hobbs, Stevie Branch’s stepfather.

A hair found tangled in a knot tied by the killer that didn’t belong to one of the teenagers. At the very least, that single hair posed a huge obstacle for the prosecution.

While Damien Echols’s lawyers awaited final results, they contacted me. They wanted me to examine the boys’ wounds and Dr. Peretti’s autopsy for any details the forensic pathologists, cops, lawyers, and judges might have missed. I agreed.

Read more from Vincent DiMaio’s new book Morgue: A Life in Death here at CriminalElement.com

I was familiar with the case. As I’ve said before, the forensic community is small, and the news media is pervasive. I had recently retired after twenty-five years as the Bexar County medical examiner and now was consulting on a variety of forensic cases that needed a “second look.” I knew what a lot of people knew about this particular grisly crime, and I’d had a few casual conversations with other medical examiners about it. I knew Dr. Peretti well and thought he was a good pathologist. In one of the most scrutinized cases in modern history, I doubted that I’d find anything new, much less evidence that would change everything.

Within days, a package arrived at my house. It contained hundreds of pages of autopsy reports, testimony, other experts’ conclusions, and legal opinions. Most important, it contained a binder and compact disc with nearly two thousand high- resolution, full- color crime scene and autopsy photos.

Very quickly, just as in the Wyoming case, I saw a problem.

The horrific genital mutilation on Chris Byers was not in fact done by a human. It was caused by animals gnawing on the soft tissues after he died. Bruises and gashes in the boys’ mouths— first interpreted as evidence of forced oral sex were also caused by animals. Those strange punctures on the skin that looked like knife-inflicted torture? Animals nibbling and chewing. The huge bloodied patch on the left side of Stevie Branch’s face? Also animal damage.

Similarly, the knife wounds and scrapes Dr. Peretti saw on the bodies were not inflicted by a blade but were the tooth and claw marks of feeding animals.

What animals? Snapping turtles, possums, feral cats, foxes, raccoons, squirrels, stray dogs, and the occasional coyote inhabited the Robin Hood woods. Any or all of these predators could have been attracted by the scent of fresh blood, found the bodies very quickly, and nibbled on the softest parts, which were most easily chewed off. To me, they looked like turtle bites.

The makers of the 2012 documentary, West of Memphis, tested the theory. They released several snapping turtles, like those found in the West Memphis area, near a pig carcass. The wounds they inflicted in a very short time looked nearly identical to the wounds I saw in the autopsy photos, wounds that investigators and prosecutors attributed to a serrated- blade knife and occult rituals.

It’s an unsavory reality: At the moment of death, a human body becomes food. Bacteria, insects, and animals begin to recycle dead muscle, fat, fluids, and other tissues into their own life- sustaining nourishment. They don’t allow a proper interval for grief, meditation, or cooling. The bacteria are already inside, mostly in the intestines, and they don’t die when their host dies; insects and wild animals might take a little longer to find a dead body left in the open, but usually not more than a few minutes.

But there was more to suggest that the evidence jurors heard was not what it seemed.

The boys’ dilated anuses were interpreted by the original medical examiner as possible evidence of forcible sodomy, either by a penis or another object. In fact, a dilated anus is a normal postmortem artifact. After death, the body’s normal muscle tension relaxes. Sphincter muscles loosen, too, and if submerged in water for a time, can look misshapen and stretched. I saw no evidence of any anal trauma, and I don’t believe any of the boys was sodomized.

And Stevie Branch’s halfway discolored penis, which was interpreted as evidence of forcible oral sex, was simply caused by the positioning of his body after death, not by a sexual trauma. These boys were obviously murdered, but the evidence didn’t necessarily add up the way cops and prosecutors said.

At the time, I didn’t know that a single hair found in one of the shoelace knots matched the DNA of Stevie Branch’s stepfather, Terry Hobbs (plus about 1.5 percent of all humans). It generated an intriguing question: How could such a hair be tangled inside a knot that trussed up a little boy moments before he was murdered if his killer hadn’t tied the knot?

Hobbs, who had a history of domestic violence, has steadfastly denied all implications and accusations—and there have been many— that he killed the boys. He claims Stevie could have transported the hair on his clothing and it was caught up in the vicious assault. No charges have ever been brought against him, although the angry debate rages among the West Memphis Three partisans to this day.

Vincent J. M. DiMaio, MD, is a pathologist and internationally renowned expert on gunshot wounds. Now a private consultant who’s performed more than 9,000 autopsies, he’s played pivotal roles in some of the most provocative trials and death investigations of the past 40 years. He is the author of MORGUE: A Life in Death.

Ron Franscell has traversed the open range of journalism, fiction and nonfiction. His journalism has won several national awards, including the Associated Press Managing Editors’ national Freedom of Information Award. He is the co-author of MORGUE: A Life in Death.