by Peter Snow

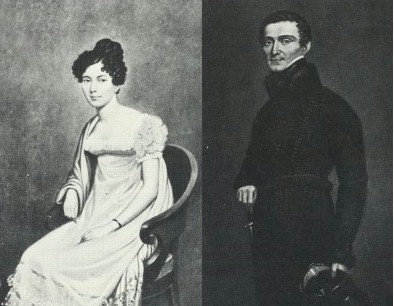

Harry and Juana Smith

Many a soldier has had an exciting life. It’s not often that a solider shares the excitement and danger with his wife. But it is true of one redoubtable young officer and his attractive Spanish wife two hundred years ago. Harry and Juana Smith. Harry Smith was an army Captain in the Napoleonic war between Britain and France. He met his wife in extraordinary circumstances. Juana Maria de los Dolores de Leon was a 14 year old member of a distinguished family from northern Spain living in the town of Badajoz near the Portuguese frontier. Its massive fortifications made it a natural stronghold for Napoleon’s forces to seize and garrison when the French Emperor occupied Spain and Portugal in 1807. Britain was locked in a struggle for survival with Napoleon and In 1808 Sir Arthur Wellesley – later the Duke Wellington – landed an army in Portugal intent on liberating the Peninsula and pushing the French back where they came from. Nearly every step Wellesley took brought success after success. Harry Smith, a young blade, 21 years old with a bit of a swagger, was a Lieutenant in the elite 95th Rifles: they were sharpshooters trained to fire the new rifle which had a range far in excess of the ordinary infantryman’s musket. Smith was from Whittlesey in the Isle of Ely. He was not tall; he was neat, and elegant with curly hair and an accomplished horse rider who loved the hunt. He spoke fluent Spanish, which served him and Wellesley’s army well as Spanish guerrillas resisting the French occupation worked closely with the British.

By 1812 Smith, now a seasoned company commander and Wellesley, now honoured with the title Lord Wellington, had pushed the French out of Portugal and were advancing into Spain. One formidable obstacle stood in their way – the fortress of Badajoz powerfully placed on the River Guadiana in south western Spain and commanding a major road to Madrid. It had to be suppressed and the 95th would be in the forefront of Wellington’s assault troops. Smith was in the thick of the dreadful carnage his regimental mates suffered as they attempted to storm the breach by the Santa Maria bastion. Badajoz was well defended by the French and its walls were high: even when they were breached by Wellington’s cannon, their defenders exacted a terrible toll. Wave after wave of British infantrymen was cut down and Wellington and his staff were near despair. ‘It was appalling. Heaps on heaps of slain – in one spot lay nine officers’, wrote Smith. Then when it was already deep into the night of 6 April, General Thomas Picton’s 3rd Division scaled the walls of the castle in the northeast corner of the city and the French collapsed. Badajoz fell and the road to Madrid was open.

But the price paid by Badajoz’s defenders and its innocent Spanish civilian population caught between the two protagonists was horrific. Harry Smith witnessed the enraged British soldiers brutally avenging their fallen comrades. ‘The atrocities committed by our soldiers on the poor innocent and defenceless inhabitants of the city no words suffice to depict.’ They raped, pillaged, and drank their way through the rest of the night and even the civilian population of Badajoz suffered. Harry Smith and a friend were out in the streets of the ravaged city when two young Spanish women came towards them with blood streaming down from their ears. The two officers horrified at the womens’ condition asked what had happened. ‘Your rampaging soldiers tore off our ear-rings,’ they replied. At which Smith and his friend immediately insisted on taking the two women under their care. The younger woman was, in the words of Harry Smith’s friend, ‘transcendingly lovely…with a face so irresistibly attractive…that to look at her was to love her.’ What left Smith’s friend stunned was that no sooner had he and Harry escorted the two women back to their camp than Harry had proposed to the younger one, Juana, and she had rapidly accepted him. Harry Smith left his friend flabbergasted and most of his mates in the regiment thought he’d taken leave of his senses. She was a Catholic, he was a Protestant, and he was approaching the peak of a very active career constantly campaigning: the last thing he should do was saddle himself with a fragile new wife who would now have to accompany the army through the Peninsula.

But Juana Smith turned out to be anything but fragile. She threw herself into the hardships of camp life and long distance marching as if she’d spent her short life preparing for it. What was more the Duke of Wellington, who had already taken Harry under his wing, agreed to give Juana away at her marriage to Harry 12 days later. She was utterly devoted to him, as he was to her. And soon won the admiration and affection of Harry Smith’s comrades. When he came to write his autobiography nearly half a century later when they were General Sir Harry and Lady Smith, he described her as his ‘guardian angel.’ For the next two years, through the searing summers and bitter winters of the Peninsula and the Pyrenees Juana followed Harry through the rigours of the campaign that eventually threw Napoleon’s armies out of Spain and across southern France.

Juana’s stamina and charm throughout this harrowing time delighted Harry and captivated the officer and men he campaigned with including Wellington himself. ‘There was not a man who would not have laid down his life to defend her,’ wrote Smith later. Smith’s first task was to find Juana a mount. She had only ridden a donkey before: she was given one of the more placid Portuguese horses in Smith’s hunting stable but she insisted on riding a large Spanish thoroughbred called Tiny. She was soon as agile in the saddle as a cavalry trooper. After each battle Juana, like other army wives, had the distressing job of searching the field for her husband. At the battle of Vitoria in the summer of 1813, Harry’s horse collapsed on top of him and the rumour went around that he was dead. Juana was desperately anxious and it was some time before she discovered that neither Harry nor the horse was hurt. He’d scrambled out from under and revived the horse with a kick on the nose.

Smith, with Juana never far behind, fought his way through the Peninsular campaign and played his part in Wellington’s string of victories. He was a staff officer much of the time, Brigade Major in one of the Light Division brigades, and although he was only officially a Captain, he was always close to those in command. He was often bluntly outspoken in his criticism of his superiors. But forthright and ambitious though he was, Smith commanded respect and when the Peninsular campaign wound up in the spring of 1814, he soon found himself in demand for an influential role in one of the most audacious military enterprises of all time. It was the only campaign on which Harry and Juana Smith would not accompany each other.

Wellington’s army had crossed the Pyrenees in the winter of 1813 after slowly but surely pushing Napoleon’s forces out of Spain after the Battle of Vitoria, and worsting Marshal Soult’s efforts to reverse his advance at the River Nive in December, at Orthez in February 1814 and finally at Toulouse in April. Shattered by this and – more importantly – by the overwhelming weight of his opponents in central and Eastern Europe who defeated him at the Battle of Leipzig, Napoleon abdicated and was exiled to Elba. Europe sighed with relief, and the victors made ready to go home. For the Smiths it would be the end of daily anxiety and the prospect of a carefree life in England. But, wrote Smith, ‘My happiness and of indolence and repose was doomed to be of short duration.’ His commanding officer summoned him and told him that he was off to America. The war of 1812, a tiresome conflict that the United States had begun when Britain interrupted American trade with France, suddenly loomed large. The Americans, furious that the Royal Navy was interfering with their ships, had invaded Canada. The order came from Whitehall: the Americans must be given ‘a good drubbing.’ One of Wellington’s respected Peninsular veterans, Major-General Robert Ross, was to command a task force that would invade the eastern seaboard of the USA, and Harry Smith was a natural choice for a senior role on Ross’s staff. Smith was desperately torn: as an aspiring officer he had no choice. ‘But I knew I must leave behind my young, fond and devoted wife, my heart was ready to burst, and all my visions of our mutual happiness were banished in search of the bubble reputation.’ Juana was distraught but recognized that Harry was determined not to miss such an opportunity.

The couple spent a few days drifting down the River Garonne in a small skiff. It was a delightful trip and the beauties of the scenery and the spring foliage did much to relieve Juana’s worry about her uncertain future in a strange country. But Harry’s brother Tom undertook to look after her, and the Smiths parted at the end of May. ‘I left her insensible and in a faint,’ recalled Harry, as he sailed off across the Atlantic in the 74 gun Royal Oak .

Juana was glad to have the company of Harry’s brother Tom, who’d served in the Peninsula, as she traveled to Britain for the first time. Tom found her accommodation in London and told her that her horse, Tiny, was happily lazing with all the other Smith horses and ponies at their place in Whittlesey. Wouldn’t Juana like to go there and meet the family? No, she said, she was too shy to confront them until Harry came home: she was happy to stay in London and study English with a tutor. It wasn’t till September – four months after she’d arrived in England that she got her first letter from Harry.

It had been written from Bermuda, where Harry’s ship had called on its way to the United States. He had written it before he and the army arrived in America. By September the astonishing military adventure in which Harry played a major role was over. On the 20th August, Maj Gen Ross – with Harry Smith a senior staffer – landed his force of 4,500 British troops, most of them grizzled veterans of the Napoleonic war in Europe, on a river bank 50 miles southeast of Washington DC. This city was the brand new capital of the 30 year old United States. It still had a tiny population of only 8500 people but boasted the two most precious buildings in the new nation – the Capitol that housed the two houses of Congress and the President’s House, already becoming known as the White House.

There was immediate pandemonium and panic in Washington as Ross marched his army briskly up to the crossing of the eastern branch of the Potomac at a small town called Bladensburg. Drawn up on the other side of the river was the 6500 strong US army, largely composed of poorly trained militiamen. And the battle that followed was one of the most shameful defeats in US history. Faced with the battle-worn redcoats the Americans fled, abandoning the field and the city of Washington to the enemy. Smith was one of the forty or so British officers who accompanied Ross into the empty White House and found it too abandoned by the President, James Madison, and his wife Dolley. In their rush to leave the President’s staff had left dinner on the table, with the meat still roasting in the spits. Harry and the others sat down and made short work of it and then piling the chairs on the table they set light to the great mansion. ‘I shall, never forget the majesty of the flames’, Harry remarked but at the same time he admitted that he personally regarded the burning of Washington as ‘barbaric.’ To complete the utter humiliation of Madison’s government, the British went on to burn Congress, the Treasury, the State Department and the War department.

Within days Harry was given the important mission of reporting what Ross could fairly claim to be a triumphant success to the government in London. He felt doubly blessed: he would be the bearer of great news and he would see Juana again soon after she received the letter he’d written weeks earlier. Washington was burned on 24 August: on 22 September his wife Juana stepped out of her house into Panton Square and saw a taxi draw to stop beside her. ‘Oh, Dios la mano de mi Enrique’ she cried ’Oh my God, my Enrique’s hand.’ ‘Never shall I forget that shriek..as we held each other in an embrace of love few can ever have known,’, recalled Harry.

The next day Smith was off to take the news to the Prince Regent. He was a bit nervous and the War Minister who accompanied him into the royal presence told him not to forget to remain with his face always turned to the Prince. Harry was pleased to sense that the Prince seemed to be as shocked as he had been that a British army had torched the shrines of democracy in the United States. As he carefully backed out of the room as instructed, Harry was delighted to hear the Prince say to the minister, ‘Don’t forget this officer’s promotion.’ Before he went back to join Juana that night, Smith was invited to dinner at the Minister’s house and he remarked to his next door neighbor at the tables how well he knew and admired the Duke of Wellington. ‘I am glad to hear it, said his neighbor, ‘he is my brother’.

Harry Smith had promised Maj Gen Ross that he would also visit the General’s wife, Elizabeth, and he and Juana set off to Bath the next day to visit her. They carried the heartening news of Ross’s success in Washington: the tragedy was that even as they chatted joyfully, Elizabeth’s husband was dead. As his army approached Baltimore, determined to deliver the same punishment he had inflicted on Washington, he was killed by an American sharpshooter’s rifle shot. Smith claims – with the hindsight of an autobiography writing several years later – that he had warned Ross not to attack Baltimore. Whether or not we believe him, the enterprise was a failure. The British were rebuffed by far stronger opposition than they’d encountered at Washington, and their lifting of the bombardment of Baltimore inspired the words of the US national anthem.

Smith now finally persuaded his young wife that she should meet his family and they all spent a very happy three weeks in Whittlesey with Juana’s English improving by the day. But it was short lived: a letter from Whitehall soon parted the couple again. After the failure of Baltimore and the death of Ross, a new effort was to be made to bludgeon the Americans in to agreeing an end to the war. Wellington’s brother in law, Maj Gen Edward ‘Ned’ Pakenham was to lead a reinforced army against the city of New Orleans in order to seize and control the mouth of the great Mississippi river. Once again Harry would be a senior staff officer. ‘It once more raised that blighted word ‘separation’ to be imparted to my faithful and adoring wife.’ This time Juana stayed on with the family in Whittlesey.

New Orleans was an even greater disaster than Baltimore. In a badly mismanaged attack on a well fortified US line on the banks of the river the British were soundly beaten and Andrew Jackson’s Americans triumphant. Smith was sent bearing a flag of truce to ask the Americans to allow the British to bury their dead. ‘They fired on me with cannon and musketry, which excited my choler somewhat’, but he finally won agreement from General Jackson. Smith then found himself shoveling 200 bodies into a specially dug hope in the ground. ‘A more appalling spectacle cannot well be conceived than this common grave, the bodies being hurled in as fast as we could bring them.’

There is a sad irony about the Battle of New Orleans celebrated in Lonny Donnegan’s well known song – ‘We fired once more and they began to runnin‘ down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico‘. A whole two weeks before the battle was fought , the British and Americans had signed up to peace in Ghent in Belgium. The news didnt reach the USA until February. Some 700 men had died in vain.

In March, with the US war over and the real prospect of a general peace, Harry Smith was on his way home again – once more aching to see his wife – but no sooner had his ship reached the western approaches to Britain than he heard the news – shouted across the water from a vessel going the opposite way – that Napoloen had escaped from Elba. ‘ Such a hurrah as I set up, tossing my hat over my head! I will be a Lieutenant Colonel before the year’s out‘, Harry recalls exclaiming at the time. Harry was not surprised when he was asked by a General he had impressed in the American campaign to accompany him as his brigade major to the new front against Napoleon in Belgium. But this time he was determined to take Juana with him. He had bought two horses at Newmarket, one for Juana ‚ ‘a mare of great celebrity‘, and one for himself and they were shipped with the Smiths to Ostend. Harry reports that, far from being apprehensive at the prospect of battle, Juana was thirsting for action. ‘My wife was delighted to be once more in campaigning trim.‘

Harry was with Wellington on the morning of 18 June on the ridge of Mont St Jean just south of the village of Waterloo. ‘It was delightful to see his Grace that morning on his noble horse Copenhagen – in high spirits and very animated but so cool and so clear on the issue of his orders..‘ Smith had told Juana to await him in Brussels a few miles to the north. Napoleon in a lightning campaign had marched from Paris with 130,000 men and crossed into Belgium intent on breaking through to Brussels. Two armies stood in his way, Marshal Blucher’s Prussians and Wellington’s army of mixed allies and British. In a brilliant stroke Napoleon had thrown his army against the Prussians and forced them from the field at the battle of Ligny on 16 June. Blucher, beaten but still defiant, retreated to a town named Wavre where he judged he could still march to Wellington’s aide if Napoleon attacked him. And he actually promised the Duke that he would do so.

On the morning and afternoon of the 18th, believing that the Prussians were safely out of reach Napoleon made a series of massive attacks on Wellington’s ridge. Smith was constantly racing to and fro carrying orders to the brigade he was attached to. The battle was as hard fought as any in history: Wellington described it as ‘hard pounding‘. His task was to hold the line of the ridge against repeated French infantry and cavalry attacks until Blucher could come to his aid. ‘Every moment,‘ wrote Smith, ‘was a crisis…Every staff officer had two or three (and one four) horses shot under him. I had one wounded in six, another in seven places, but not seriously injured.‘

But by the end of the day, with Blucher in the nick of time forcing back Napoleon’s right, the French Emperor was unable to press Wellington as hard as he would have liked, and the final climax, witnessed by Harry Smith from afar, came with the crushing of the French Imperial Guard’s assault at around 8pm. Utterly defeated the French fled from the field and Napoleon rode back to Paris and eventual exile on the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic. Blucher and Wellington shook hands and then took stock of the appalling aftermath of the battle. 45,000 dead and wounded lay on the field. ‘I had never seen anything to compare with what I saw,’ said Smith, ‘At Waterloo the whole field from right to left was a mass of dead bodies.’ He saw French horsemen in their metal breastplates literally piled on each other. Many unwounded men were still trapped under their horses, others fearfully wounded struggling to free themselves from the horses lying on top of them. ‘The sight was sickening, and I had no means or power to assist them.’

If it was a wretched experience for Harry Smith, it was a nightmare for Juana. She had ridden all the way to Antwerp on the advice of an officer who said she would be safe there, and when she heard of the British victory she raced back to Waterloo searching for her husband. Imagine her horror when she ran into a group of 95th riflemen and they told hern that Brigade-Major Smith had been killed. She was beside herself with distress and rode frantically around searching for his body. She herself wrote later: ‘I approached the awful field of Sunday’s carnage, in mad search for Enrique. I saw signs of newly dug graves and then I imagined to myself: ‘O God he has been buried and I shall never again behold him.‘ Then suddenly she ran into an old friend Charlie Gore and she asked desperately ‚Oh where is he, Where is my Enrique?‘ ‘Why , near Bavay by this time, as well as ever he was in his life; not wounded even..‘ ‘Oh dear Charlie Gore, why thus deceive me? The soldiers tell me Brigade–Major Smith is is killed‘. ‘Dear Juana, believe me; It is poor Charles Smyth‘, replied Gore, ‘Brigade-Major to Pack…Why should you doubt me?‘. ‘Then God has heard my prayer,‘ said Juana , with massive relief. She didn’t reach Bavay till the next morning. ‘Oh Gracious God I sank into his embrace, exhausted, fatigued, happy and grateful ..‘

It had been the most agonizing moment in one of history’s most striking relationships: from then on the Smiths were not often parted for long. Harry Smith went on to command – often with distinction – in a long career that took him to France , Canada, ,Jamaica, India and South Africa, where he was Governor and Commander in Chief in the Cape in the early 1850s. The South Africans named two cities after them: Harrismith and Ladysmith. Harry died at the age of 73 in 1860, and Juana died twelve years later in 1872. They were buried together in Whittlesey.

PETER SNOW is a highly respected journalist, author, and broadcaster. He was ITN’s Diplomatic and Defense Correspondent form 1966 to 1979 and presented Newsnight from 1980 to 1997. An indispensable part of election nights, he has also covered military matters on and off the world’s battlefields for forty years. Peter Snow is the author of When Britain Burned the White House.