dd

dd

dd

dd

By Fred Pushies

Marines are no strangers to the unconventional element of warfighting. The very nature of the Corps, the training and missions, elevates the Marines to the ranks of an elite. On occasion throughout the course of history, these select few have risen beyond the conventional warfighting role and prepared for and executed operations on par with any special operations unit past or present.

Less than twenty years after its war for independence, the fledgling United States of America would wage its first conflict on foreign soil at the beginning of the nineteenth century: the Barbary War (1801–1805). The North African Barbary coast was comprised of four states, nominally ruled by the Turkish Ottoman Empire but in practice given considerable autonomy in which to conduct their affairs: Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. Sailing in the region were the Barbary Pirates, also known as the Barbary Corsairs, who roamed the waters taxing vessels, attacking ships, and capturing their crews. These Muslim pirates operated much like the Somali pirates of today, but with the sponsorship and support of their Arab rulers.

In the years following American independence, the major European powers paid tribute to the Barbary States in return for their ships being left to ply the Mediterranean unmolested, and the United States did the same. By 1801, however, the United States was behind in its payments, and in that year the bey (ruler) of Tunis, Yusuf Caramanli, declared war in the hope of collecting his tribute by force from the American ships his pirates attacked.

In response, President Thomas Jefferson deployed an armada of frigates, including a Marine expeditionary force, into the Mediterranean in order to defend America’s interests in the region. By 1803 the Navy ships had established a blockade of all ports on the Barbary Coast, and its warships were attacking the Barbary Pirate vessels on a regular basis. As in all wars, there are times when the tides shift and the enemy goes on the offensive. Such was the case in October 1803, when the pirates captured the USS Philadelphia, which had gone aground while patrolling in Tripoli harbor. The pirates captured the ship, and her captain, William Bainbridge, along with all the officers and crew, was taken ashore and held hostage. The pirates then turned the guns of the frigate against the other U.S. ships. In February 1804, Navy lieutenant Stephen Decatur led a small contingent of eight U.S. Marines in a covert mission to attack the captured ship. Overpowering the guards the men set fire to the ship, denying its use as a gun battery to the enemy. British vice admiral Horatio Nelson reportedly stated, “[the raid] was the most bold and daring act of the age.”

During this same time, further acts of heroism occurred that would secure the Marines a place not only in military history, but also in the realm of unconventional warfare. On March 8, 1805, 1st Lt. Presley O’Bannon led the Marine detachment consisting of a sergeant and six privates in an unprecedented operation to attack the fortified Tripoli city of Derna and rescue Philadelphia’s crew. The Marines linked up with a diplomat turned Navy lieutenant, William Eaton, along with five hundred Greek, Arab, and Berber mercenaries. The coalition force began its mission in Alexandria, Egypt, and traversed six hundred miles of the Libyan desert to assure it the element of surprise.

On March 27 the force reached the city of Derna, where they proceeded to carry out a two-pronged attack; Eaton’s force attacked the governor’s castle, while O’Bannon led his Marines in a frontal assault on the harbor fort. Braving a hail of musket balls from the defenders, O’Bannon and his men managed to overrun the enemy positions, forcing them to leave with the fort’s cannons primed and unfired. The Marines took control of one of the batteries and turned the guns upon the enemy. It was then when O’Bannon placed the American flag upon the ramparts of the fort. After two hours of hand-to-hand fighting, the stronghold was occupied, and for the first time in history, the flag of the United States flew over a fortress of the Old World. The Tripolitans attempted to counterattack the fort several times, yet each time they were repelled, sustaining heavy losses in the process.

The Marines’ victory helped Hamet Caramanli, Yusuf’s deposed brother, reclaim his rightful throne as ruler of Tripoli. In gratitude, he presented his Mameluke sword to Lieutenant O’Bannon. This famous sword became part of the officer uniform in 1825, and remains the oldest ceremonial weapon in use by U.S. forces today. Derna was the Marines’ first battle on foreign soil. Lieutenant O’Bannon and his men are immortalized in the “Marines’ Hymn”: “From the Halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli, we fight our country’s battles in the air, on land and sea.”

By the late 1890s, Spain had lost much of its power in the world, with the exception of Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean, and the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific. The sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, Cuba, on February 15, 1898, triggered the start of the Spanish-American War. The Marines, through their actions at Guantanamo Bay and Guam, proved that a small team of men could be rapidly deployed and successfully conduct amphibious operations. By August 12, hostilities

had ceased. Though short in duration, the four-month war had transformed the United States into a major world power.

Throughout the late nineteenth century, though their numbers declined, the Marines did battle and protected American interests from Formosa and Korea to the Philippines and China, making use of their expertise in small-unit tactics against the enemy.

As the world entered the twentieth century, the Marines answered the call anew, projecting a U.S. sea-based power whenever the United States needed a rapid response force. The early years saw the Marines active in Central and South America, in what became known as the “Banana Wars.”

Their experiences in Central America and the Caribbean led the Marines to begin systematically analyzing the nature and requirements of operations short of war proper or “small wars.” Major Samuel M. Harrington of the Marine Corps Schools delivered a formal report, The Strategy and Tactics of Small Wars, in 1922. In addition, Major C. J. Miller wrote a 154-page report on the 2nd Marine Brigade’s operations in the Dominican Republic titled Diplomacy and Spurs in the Dominican Republic in 1923. These and similar Marine publications were inspirational in the first publication of Small Wars Operations in 1935. The 1940 version was renamed the Small Wars Manual, and remains relevant today as the foundation of a good deal of current thinking and doctrine.

As the twentieth century progressed, the Marines handled an assortment of missions that, by today’s standards, would be considered direct action (DA) operations. It would be during World War II, however, that the Corps would first create units specifically trained and equipped with the precise objective to carry out special operations.

Marine Raiders

With the United States fully committed to World War II following the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt became interested in the creation of a unit on par with the British Commandos. After some deliberation by Maj. Gen. Thomas Holcomb, commandant of the Marine Corps, he selected the term “Raiders” and created two battalions. The 1st Raider Battalion was activated on February 16, 1942, followed by the 2nd Raider Battalion on February 19, 1942. Lieutenant Colonel Merritt “Red Mike” Edson would command the 1st Raider Battalion and Lt. Col. Evans Carlson commanded the 2nd, thus earning them the names Edson’s Raiders and Carlson’s Raiders, respectively. Two months later, on April 12, 1942, the Raiders were deployed from the United States en route to American Samoa.

The Marine Raider battalions were designed on similar parameters to today’s special operations forces. Each consisted of lightly armed, intensely trained units established by the Marine Corps during World War II. This elite group of Marines would be tasked with three missions: spearhead larger amphibious landings on beaches thought to be inaccessible, conduct raids requiring surprise and high speed, and operate as guerrilla units for lengthy periods behind enemy lines. Having been given the directive from the president, the Raiders enjoyed wide latitude in the acquisitions of weapons and equipment. Whether it was part of the Corps standard issue or not, the Raiders got priority, no questions asked. This included manpower, as the battalions sought after and received the best of the Marine volunteers available.

Edson retained the traditional eight-man squad, made up of a squad leader, two Browning automatic rifle (BAR) men, four riflemen armed with M-1903 Springfield rifles, and a sniper. In contrast, Carlson departed from the norm, organizing his battalion into ten-man teams that included a squad leader and three fire teams of three Marines apiece. These Marines were armed with Thompson submachine guns, BARs, and M-1 semiautomatic rifles.

On August 7, 1942, in the first American offensive of World War II, the 1st Raider Battalion went ashore at Tulagi in the Solomon Islands. It would take three days of intense fighting before the Marines killed all of the Japanese on the island, where the enemy fought to the death. After three weeks, Edson’s Raiders were relocated to Guadalcanal to assist the Marines there in the defense of Henderson Field. At this time, the Raiders continued seek-and-destroy missions against the enemy in a bold raid against approximately one thousand Japanese troops located in the village of Tasimboko. The surprise attack caught the Japanese soldiers off guard, forcing them to abandon their weapons, communications, supplies, and a unit of artillery, all of which the Marines destroyed.

Colonel Edson believed the Japanese forces that had fled during his attack at Tasimboko would attempt to strike Henderson Field. He received the 1st Marine Division’s permission to occupy Lunga Ridge located south of Henderson Field in September 1942. The Raider Battalion was reinforced by two companies of the 1st Marine Parachute Battalion.

Edson’s Ridge

What was supposed to be a short rest for the Raiders would turn into a fight for their lives. On the evening of September 12, the Japanese unexpectedly attacked their position in an onslaught that included a naval bombardment by a cruiser and three destroyers. This heavy fire forced Edson’s force to withdraw to a reserve location. At first light on September 13, Allied aircraft and Marine artillery rained down on the Japanese, forcing them to withdraw from the ridge. Expecting the enemy to attack again, Colonel Edson repositioned his men and instructed them to improve their positions on the ridge.

By this time the Marines were low on ammunition and supplies, but their spirits were high, having been motivated by Colonel Edson, who reportedly told them, “You men have done a great job, and I have just one more thing to ask of you. Hold out just one more night.” And hold out they did, digging in and mustering up the courage, honor, and commitment to battle through the night. More than 2,500 Japanese soldiers repeatedly attacked Edson’s Raiders and the Paramarines, whose numbers totaled only eight hundred. When the battle was done, the ground was strewn with the bodies of Japanese soldiers. Colonel Edson and the Marines continued to hold the high ground. The battle that ensued became known as “Bloody Ridge” and eventually as “Edson’s Ridge,” and has become one of the legendary accounts of courage and tenacity in which

the U.S. Marines prevailed despite overwhelming odds during the Pacific Campaign.

Makin Island Raid

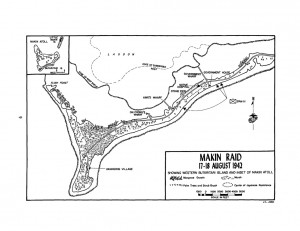

On August 17, 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Carlson led the 2nd Raider Battalion on a raid against Japanese forces on Makin in the Central Pacific. The island was triangular in shape and covered in dense coconut palms from the waterline inland. The objective of the mission was to destroy the enemy installation on the island, capture prisoners, and gather intelligence on the Gilbert Island region. The raid was also intended to divert Japanese attention and reinforcements from the Allied landing on Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

The Raiders consisted of two rifle companies and a contingent of the battalion command group. Battalion headquarters, Company A, and eighteen men from Company B (totaling 121 Marines) were embarked aboard the submarine Argonaut (APS-1), and the remainder of B Company (totaling ninety Marines) was embarked aboard the submarine Nautilus (SS-168). The raiding force was designated Task Group 7.15.

Upon reaching their insertion point at 3:00 a.m., the submarines surfaced, and the Raiders were transferred to rubber rafts. Heavy swells created problems for the Marines as they transitioned from the subs to the rafts, as well as swamping the outboard motors. For these reasons, the original plan of landing the Marines on two separate beachheads was abandoned, and Colonel Carlson ordered the Raiders to follow him to the landing zone, code-named “Z.” Fifteen of the eighteen rafts hit the beach along with Carlson, while two others landed approximately a mile north. The last of the rafts landed over a mile to the south, placing the Marines well behind Japanese lines.

Other than the environment obstacle, the Raiders landed unopposed by the occupying Japanese force. Colonel Carlson ordered Company A to head across the island and capture the lagoon road. By 6:00 a.m., the Marines had reached the Government Wharf and reported seizing the objective without enemy opposition. The smoothness of

the raid suddenly ended, however, as 1st Platoon, Company A, made contact with enemy forces and met heavy resistance. The Japanese infantry was armed with four machine guns, a flamethrower, grenade launchers, and automatic weapons, as well as snipers. The battle raged on for more than five hours, until another platoon from Company A broke through and flanked the enemy positions.

While Marines had been fighting, a Japanese transport ship and patrol boat had entered into the lagoon. These two ships would never pose a threat to the Raiders, however, as both enemy vessels were sunk by the deck guns of the American submarines on station. Two hours later a flight of twelve Japanese aircraft arrived, consisting of two Kawanishi H6K flying boats, four Nakajima A6M2-N fighters (Zeroes), four Kawanishi E7K2 Type 94 reconnaissance bombers, and two Nakajima E8N2 Type 95 recon planes. The flying boats landed to deliver reinforcing troops, only to be destroyed by gunfire from the Raiders. The other enemy planes flew over the island for more than an hour, sporadically dropping bombs and making strafing runs but failing to kill any Marines.

At 7:30 p.m., as scheduled, the Raiders began their withdrawal from the island, using the same eighteen rafts on which they had come. Though the Marines had practiced surf passages and raft operations extensively, the heavy sea conditions washed many of the rafts back to shore. Only seven of the rafts made it back to the submarines; the balance of the Raiders remained on the island.

On the morning of August 18, the submariners dispatched a rescue raft to deploy a rope that would allow the Marines to be pulled out through the rough surf. However, a group of Japanese aircraft arrived and began attacking the waterborne Americans, forcing the submarines to crash-dive and remain submerged for the balance of the day.

The Raiders were able to get a signal to the submarine and arrange a new rendezvous for 11:00 p.m. at the entrance of Makin Lagoon. The Marines did what Marines still do today: they adapt, improvise, and overcome. Using their four remaining rafts and two native outriggers, the Raiders headed out to sea at 8:30 p.m., arriving alongside the Nautilus at 11:08 p.m., just off the entrance to the lagoon, Flink Point. Seventeen of the Raiders were wounded and thirty-one others remained unaccounted for. It was later learned that nine of them were still alive on the island after the last evacuation, were captured by the Japanese and transported to Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands. There, Rear Admiral Koso Abe, commander of the 6th Base Force, ordered them beheaded.

Although the Raiders accomplished their mission of decimating the Japanese garrison on Makin Island—Japanese dead were estimated at anywhere between 83 and 160—the overall evaluation was that it had failed to meet the strategic goals of the operation. No enemy prisoners had been taken, and no workable intelligence collected. The raid did prove useful, however, in testing the Raiders’ tactics, techniques, and procedures.

Two additional Raider battalions would be created and serve operationally in the Pacific theater of operations. The Raiders would participate in twenty major campaigns and battles in the course of the war, bringing their fighting spirit and discipline to every engagement. Some Marines viewed the Raiders as an “elite within an elite,” which lead to some resentment in the Corps. As such, the majority of operations conducted by the Marine Raiders were seen as tactics that should be employed to all Marine infantry, and all of the Corps should be trained to carry out the same tactics. By February 1944, the Marine Raider battalions had been disbanded.

Paramarines

In May 1940 the commandant of the Marine Corps, General Holcomb, ordered plans for the creation of a Marine unit capable of deploying via parachute. This unit would consist of one battalion of infantry and a platoon of artillery consisting of two 75mm pack howitzers. The plan outlined three tactical mission parameters under which the Marines would be deployed: First, as a reconnaissance and raiding force that would operate under the assumption that it would potentially be unable to return to Allied lines. Second, the paratroopers could be deployed as a spearhead or vanguard to capture and hold strategic positions or terrain until relieved by larger follow-on forces. Third, the unit could act as an independent force functioning in a guerrilla warfare role behind enemy lines.

On October 26, 1940, the first group of two officers and thirty-eight enlisted men were sent to the Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, New Jersey. Here these forty Marines would begin their training, learning how to jump out of an airplane. Whether the motivation was patriotism or the lure of the extra jump pay—fifty dollars per month for enlisted and a hundred dollars per month for officers—there was no shortage of volunteers. Marines trying for a slot in the parachute skill were required to be between eighteen and twenty-two years old, single, athletic, and intelligent, with no physical or mental impairments.

The tempo of Marine training was beginning to feel the demands of the war effort. For this reason the secretary of the Navy, William Franklin Knox, approved the Marine commandant’s request to establish two Marine parachute schools. In May 1942 the Parachute School was created in San Diego, and in June the Parachute School opened at New River, North Carolina.

The 1st Parachute Battalion officially formed at Quantico on August 15, 1941, under the command of Capt. Marcellus Howard, and on July 23, 1941, the 2nd Parachute Battalion was organized at San Diego under the command of Capt. Charles Shepard Jr. The 3rd Battalion was formed on September 16, 1942, under the command of Maj. Robert Vance, and the 4th Parachute Battalion entered on April 2, 1943.

The 1st Parachute Battalion was attached to the 1st Raider Battalion, along with the 2nd Battalion/5th Marines, which made up the Marine forces landing on Guadalcanal. The 1st Parachute Battalion, which had suffered heavy casualties in the Battle of Tulagi and nearby Gavutu-Tanambogo in August, was placed under Colonel Edson’s command. The 2nd Parachute Battalion would be tasked with a diversionary raid on Choiseul Island in October 1943, and later joined the 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions on Bougainville.

In retrospect the tactical advantage of airborne troops cannot be discounted in either a full-scale war or low-intensity conflict. Nevertheless, the Paramarines were considered a luxury item the Marine Corps could neither fund or support logistically at that time in history. On February 29, 1944, the 1st Marine Parachute Regiment was disbanded.

Office of Strategic Services (OSS)

When one mentions the OSS, the average person may think of the historical link to the U.S. Army and Special Forces, which evolved from the Jedburgh teams and operations groups. The OSS, which was the forerunner of today’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), ran clandestine missions in both the European and Pacific theaters of operations. It was instrumental in gathering intelligence, conducting sabotage raids in occupied Europe, and working with French resistance fighting against the Nazis.

What may be surprising to some is that Marines were also active in this covert unit during the war. Assigned to the OSS was Marine lieutenant colonel William Eddy, who worked with the counterintelligence (CI) branch within the Office of Naval Intelligence prior to the outbreak of World War II. The head of the OSS, Army colonel William “Wild Bill” Donovan, assigned Eddy to head all undercover and subversive operations in French North Africa. Eddy coordinated efforts between the OSS, Special Operations Executive (British sabotage and subversion agency), and the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) for the Allied landings called Operation Torch. Starting on November 8, 1942, Torch would be the first military action in which the OSS provided direct support.

Another Leatherneck to operate with the OSS was Col. Peter Ortiz, then a captain, who served in both Europe and Africa. Ortiz was born in New York City on July 5, 1913, but was schooled in France, where he left prior to his graduation in order to join the French Foreign Legion. He was

wounded in action and captured by the Germans, but after fifteen months as a prisoner of war (POW), he managed to escape in October 1941. Making his way back to America, he joined the Marines on June 22, 1942, and was trained at Paris Island. In May 1943 he was attached to the OSS.

Having lived in France, Ortiz was fluent in that language as well as five others; he was also a graduate of the Marine parachute school. On January 6, 1944, he parachuted into France to assist the underground resistance forces known as the Maquis. While working with the Maquis, he also assisted in the rescue of four Royal Air Force pilots who had been shot down. In 1944, Ortiz was recaptured by the Germans and spent the remainder of the war as a POW.

Amphibious Reconnaissance Company

On January 7, 1943, the Observer Group, which had been created in 1942, was redesignated the Amphibious Reconnaissance Company under the command of Capt. James L. Jones. In the summer of 1943, the Amphibious Corps would be reorganized, and the ARC would become V Amphibious Corps, or VAC Amphib Recon Company. During operations on Apamama, Majuro, and Eniwetok, VAC Amphib Recon Company was assigned to pinpoint the location of the enemy throughout the atolls. The VAC Amphib Recon Battalion underwent further evolution on April 14, 1944, when it became the Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion with a complement of twenty officers, two hundred seventy enlisted Marines, and thirteen Navy corpsmen. Worth noting is that at the same time, Marines were attached to the “coast watcher” units, and recon teams from “Special Service Unit Number 1” served the forces in the Southwest Pacific.

A pivotal moment for the Reconnaissance Marines would come in July 1944 when Marine Lt. Gen. Holland Smith and Vice Adm. Kelly Turner disagreed on the proposed landing sites for the assault on Tinian Island. Armed with only Ka-Bar knives, the Marines of the Amphibious Reconnaissance Company, VAC, were tasked with surveying two beaches that Smith had chosen as possible locations for the landing.

Brigadier General Russell Corey (Ret.) relates: “There were two landings sites, White 2 and White 1. The beaches were about sixty yards and one hundred sixty yards respectively. [Corey] and Gunny Charles Patrick (Major, Ret.) led the two recon teams. The first night the current was so strong we could only conduct the recon on one of the beaches. The next night we returned and were able to do both landing sites.”

Based on VAC’s findings, the site choice went to General Smith, and beaches White 1 and White 2 were chosen for the landing of two Marine divisions on Tinian. General Corey adds: “Had the division gone ashore on the spot picked by Kelley, it would have been a slaughter. The Japs had gun emplacements and artillery all lined up in the Tinian Town location.” The Recon Marines had earned their pay and would see subsequent use in Iwo Jima and Okinawa, as well as other amphibious assaults in the Pacific.

Birth of Force Recon

Force Reconnaissance, as it is known today, was activated on June 19, 1957, with the creation of 1st Amphibious Reconnaissance Company, FMFPAC (Fleet Marine Force, Pacific), under the command of Maj. Bruce F. Meyers. Located out of Camp Pendleton, California, this newly organized company would be formed into three platoons: an amphibious reconnaissance platoon, a parachute reconnaissance platoon, and a pathfinder reconnaissance platoon. Subsequently, in 1958, half of the company was transferred from Camp Pendleton to Camp Lejeune, to form the 2nd Force Reconnaissance Company, FMFLANT, (Fleet Marine Force, Atlantic), under the command of Capt. Joe Taylor, and thus supported the 2nd Marine Division. Worth noting is the fact that it would be another four years before the Navy SEALs would come on the scene, and another eleven years before the Army would designate a counterpart to Force Recon with the creation of LRRPs (long-range recon patrols).

As the country progressed into a new decade, the Marines of Force Recon also advanced in their tactics, techniques, and procedures. These men, proficient in land navigations, small arms tactics, and patrolling, as well as having earned their wings, would now depart from terra firma to master the skills of attacking from the sea. Fast boats, rubber rafts, and submarines were not new to the Marines, who had used these craft as platforms during World War II and Korea. Methods of locking-in and –out of submarines and buoyant ascents all would serve the Force Recon Marines in performing their missions. While the men were honing their skills, the United States was becoming increasingly involved in the guerrilla war in the Republic of Vietnam. That conflict would prove to be a watershed for Marine Force Reconnaissance.

The Vietnam War

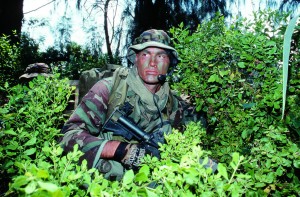

Members of 1st Force Reconnaissance Company were deployed to Vietnam in 1965, while 2nd Force had the assignment of training new Recon Marines to be sent to Southeast Asia. The Force Recon Marines at Lejeune would also serve as the primary unit should any other contingency arise elsewhere that required the attention of the Marine Corps. Sensing the need for additional reconnaissance capabilities in country, the Corps formed 3rd Force Company, per Lt. Col. Bill Floyd (Ret.): “We took the company over in September of 1965. First would make their home in Dong Ha, while 3rd was in Quang Tri.” When the Marines of Force Recon first deployed to Vietnam they were armed only with M3A1 “grease guns”; subsequently they would reequip with the M-14 and eventually with the M16 assault rifle.

Marines are taught to fight, to give no quarter, and to defeat the enemy at all costs. Conversely, reconnaissance work required stealth and patience, at times letting the enemy pass by so the team could report on their movements. The aggressiveness of the U.S. Marine was something that had to be “un-learned” in order for reconnaissance to be successful. To enhance these new skills of Force Reconnaissance companies, many of the Marines attended Recondo School taught by members of the U.S. Army 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne).

Force Recon and Battalion Recon Post Vietnam

Worth noting is that within the Marine Air-Ground Task Force there are two reconnaissance units: one of these is Force Reconnaissance Company, while the other is the Battalion Recon (sometimes referred to as Division Recon) platoon, which is under the commander of the combat element. The Force Recon Company works directly for the MEF commanding general, normally a three-star, or directly for the MEU (SOC) commander, providing tactical and strategic reconnaissance and limited scale raids (e.g., GOPLAT, VBSS, demolition raids, etc.) in the deep battlespace. Force Recon covers the commander’s area of interest: the edge of the artillery fan and beyond. The Battalion Recon covers the commander’s area of influence: within the artillery fan (approximately thirty kilometers from the forward line of troops).

The Force Reconnaissance Company will conduct operational-level reconnaissance in the deep battle areas. Conversely, Battalion Recon Marines are trained to operate just forward of the front lines, or directly in front of or alongside of the conventional Marine units. Not all Battalion Recon Marines are airborne and/or scuba qualified. While the training paths are similar for the Recon Marines, those assigned to Force Reconnaissance companies will receive more advanced skills and training, which more than match those of the special operations forces of SOCOM. This skill set allows the Force Recon Marines to excel in the area of deep reconnaissance and DA missions, well beyond the range of the Battalion Recon assets. The special skills of these Marines, from Lt. Presley O’Bannon to the Marines

of today, create a tight link between those historical units and the Marines of MARSOC.

Excerpted from MARSOC: U.S. Marine Corps Special Operations Command by Fred Pushies.

Copyright 2011 by Fred Pushies.

Reprinted with permission from Zenith Press.

FRED PUSHIES is a freelance photographer and author of more than a dozen books, including MARSOC: U.S. Marine Corps Special Operations Command, whose works focus on the elite units of the U.S. Special Operations Forces.