WCAG Heading

by Jack Kelly

WCAG Heading

WCAG Heading

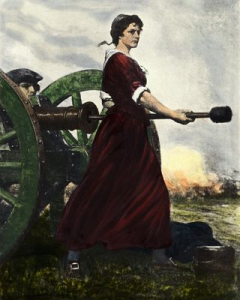

Margaret Corbin

Born on the Pennsylvania frontier, Margaret Cochran was orphaned when her parents were killed during the French and Indian war. The five-year-old was taken in by relatives and knew the pangs of poverty. She married John Corbin in 1772. When he joined the Continental Army to fight the British, Margaret went with him. Many soldiers’ wives followed the army to earn money cooking, mending, washing clothes and nursing the wounded.

In 1776, John Corbin’s artillery company was assigned to the defense of New York. The Americans tried to hold Fort Washington, which dominated the high ground at the northern tip of Manhattan Island. The enemy charged the fort from three directions. John Corbin was assisting the operation of a cannon in an outpost. When the gunner was killed, John took over. Margaret, who had watched endless gunnery drills, stepped in to help him.

John was killed by enemy bullets. Margaret continued to load and fire the big gun until she too was struck by lacerating grape shot. Wounded in the chest, shoulder and jaw, she lay bleeding as Hessian soldiers rushed by to attack the fort. The Americans lost the battle and surrendered Fort Washington. The British allowed the wounded to leave. Margaret was taken to Philadelphia for medical treatment. She lived but lost the use of her left arm.

Congress included her in the Continental Army rolls until the end of the war. She was the first woman to be granted a soldier’s pension. She lived for more than twenty years on the army post at West Point and died there around the age of fifty. A memorial stone marks her grave at the Military Academy.

Abigail Adams

Abigail married John Adams in 1864, when she was nineteen. They settled on a farm in Braintree, outside of Boston. When her husband went to Philadelphia in 1774 as a delegate to Congress, Abigail stayed behind to take care of the farm and their four children. During the war, she served on a commission to interrogate women who were suspected of Loyalist sympathies. She could hear the guns firing when the Americans drove the British from the Boston in 1776.

That same year, Abigail took a stand for women in the new nation when she wrote her husband that in making laws, “I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could.”

John was often away attending to business as a member of Congress or minister to France. The couple kept up a lively correspondence, which remains a vivid record of an eventful time and of two remarkable people. Abigail went on to become the nation’s second First Lady and mother of its sixth president, John Quincy Adams.

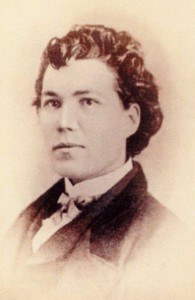

Deborah Sampson

Descended from old New England stock, Deborah was cast into poverty when her father deserted the family. She worked for years as an indentured servant, then briefly as a school teacher. Late in the war, at the age of twenty-one, she enlisted in the Continental Army, giving a man’s name. She was tall for a woman and was able to pass as a teenage boy.

Her regiment marched to West Point and was involved in a battle nearby. Deborah was wounded in the head and the leg. In order to prevent the discovery of her gender, she tried unsuccessfully to dig the bullet out of her thigh with a penknife. She became ill from the resulting infection and was sent to a hospital. A sympathetic doctor discovered her secret, but quietly passed on word that she should be honorably discharged when the war ended.

After the war, Massachusetts authorities awarded her a pension for her service. Deborah married, had three children, and returned to teaching. She organized a lecture tour to talk about her war experiences. She would put on her uniform and demonstrate the manual of arms with a musket, bringing cheers from the audience.

Sybil Ludington

In April 1777, sixteen-year-old Sybil was at her home in eastern New York when British soldiers raided Danbury, across the border in Connecticut. Sybil’s father was Colonel Henry Ludington, commander of the local militia. A messenger arrived at the Ludington home about 9 p.m. to alert the colonel to the raid.

Beside capturing or destroying a large amount of military supplies, the British were ranging the countryside, burning the homes of patriots. Col. Ludington began to organize the militia, but he needed to send word to scattered homesteads. The messenger who had arrived was unfamiliar with the territory, so Sybil volunteered. She rode more than forty miles through the dark and rain, dodging British patrols, avoiding known Loyalists, and spreading the alarm to her father’s men. The militiamen were able to mount an attack on the retreating enemy.

Sybil became known as the female Paul Revere and one of the most important women of the revolutionary war. She was honored by a postage stamp and a large bronze statue in Carmel, New York, near her childhood home.

Martha Washington

Martha is most often remembered as the original First Lady, but she played a part in the Revolutionary War as well. She was a beautiful, wealthy widow with four children when she married George in 1759. Her husband could rarely visit home after he took charge of the Continental Army, but she joined him at his headquarters whenever she could.

Martha traveled to Valley Forge in the awful winter of 1777-78, bringing supplies from Mount Vernon. She organized the wives of other officers to sew shirts and bandages for the suffering soldiers. She kept up morale by hosting modest parties and dinners.

Almost every winter during the war, Martha made the arduous journey to camp to provide support and companionship for her over-worked husband. One observer recorded of her activities: “I never in my life knew a woman so busy from early morning until late at night as was Lady Washington, providing comforts for the sick soldiers.”

Jack Kelly is the author of BAND OF GIANTS:The Amateur Soldiers Who Won America’s Independence, a journalist, novelist, and historian. He has contributed to American Heritage, American Legacy, Invention & Technology, among other national periodicals, is a New York Foundation for the Arts fellow in Nonfiction Literature, as well as author of Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive That Changed the World. He has appeared on The History Channel , been interviewed on National Public Radio , and conducted book signings across the country. He lives near Kingston in New York’s Hudson Valley, where much of the action of the Revolutionary War took place.