by Jack Kelly

In 1979, a young Vermont politician named Bernie Sanders made a short documentary film about Eugene Debs. He noted Debs’s accomplishments, he lamented the fact that Debs was largely a forgotten figure in history, and he reproduced excerpts from the speeches of a man he obviously very much admired. During his political career, Sanders has embraced many of Debs’s ideas. He even adopted Debs’s passionate, finger-pointing speaking style.

So who was Eugene Debs, and what was his role in the unions of that era, and why does his career seem so relevant today? Some remember him as the country’s first great socialist. Debs founded the Socialist Party in the 1890s and ran for president five times under that party’s banner. The last time he ran, in 1920, he was confined to a federal prison for speaking against the government—and he still got almost a million votes.

Debs helped make socialist ideas palatable to Americans. He’s the godfather of the democratic socialists who are jumping into today’s politics. Actually, many of his proposals, like publicly sponsored old-age pensions and subsidized medical care, were eventually enacted into law.

Debs saw labor and capital as equal partners who could work in harmony.

But before he was a socialist, Debs was an important nineteenth-century labor leader. When he was growing up in Terre Haute, Indiana, during the Civil War era, he loved trains. As a teenager, he found work shoveling coal into locomotive boilers. That led him to become an official in a fraternal organization for firemen, as they were called. Like many early craft unions, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen did not take aggressive steps to fight for members’ pay and working conditions. Instead, they promoted camaraderie and worked with the railroads to assure that those hired had the necessary skills.

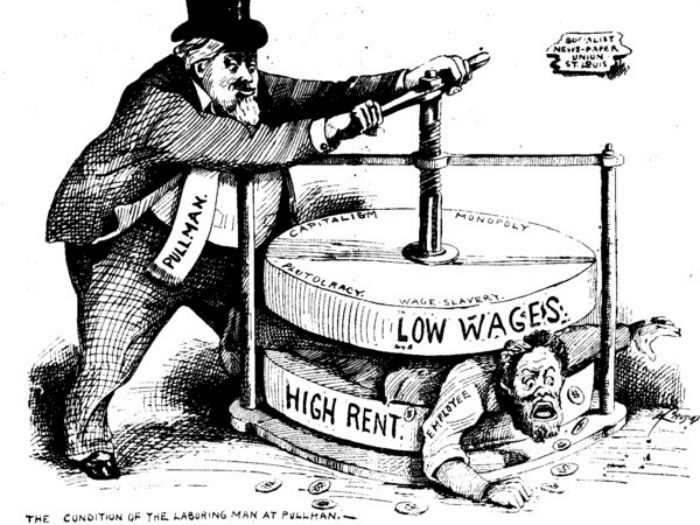

But the exploitation of workers in Gilded Age America, especially on the railroads, became more and more severe. During the 1880s, Debs rethought the whole question of labor. Low pay was an issue. Danger on the job was a particular concern for those who worked on locomotives. Brakemen had to leap from the top of one car to another in order to turn brake wheels—try that at night or in a sleet storm. An astonishing 230,000 railroad workers were killed on the job in the quarter century following 1890. That’s 23 people every day. It was clear that the railroad corporations were not going to improve the situation unless they were forced to.

Continue reading The Edge of Anarchy Part Four: The Rise of Unions on the Unknown History channel at Quick and Dirty Tips, or listen to the full episode below.