by Brin-Jonathan Butler

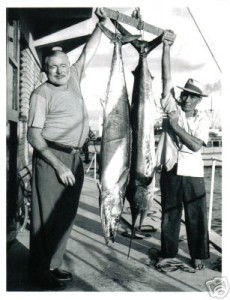

Gregorio Fuentes, the model for Hemingway’s humble Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea, survived until 104 and still never read a word of the thin, 127-page novel that brought his friend a Pulitzer and Noble Prize. Fuentes, born in the Canary Islands in 1897, had a fishing rod in his hands before he could walk. In 1919, while Hemingway was off in Italy working as ambulance driver during World War I, Fuentes permanently settled in Cuba. In 1938, Hemingway hired Fuentes to work as his beloved Pilar’s first mate. When news reached Fuentes of Hemingway’s suicide in 1961, he quietly abandoned fishing for the rest of his life. He spent his last years employed by the Cuban government to speak about his life and adventures with Hemingway for visitors who came from around the world that cared to knock on his door at his modest home on the corner of a drowsy street in Cojimar. I was one of those fortunate visitors in February of 2000 who was met with a smile after Gregorio eagerly noticed the bottle of rum and two Montecristo cigars I’d brought as presents. We only spent 20 minutes or so chatting about his life, but the experience of meeting him, hearing his voice and making him laugh, is one of my most treasured memories.

“Perhaps I should not have been a fisherman, he thought. But that was the thing that I was born for.”

Ernest Hemingway from The Old Man and the Sea

The Old Man and the Sea was the first novel I ever read. Santiago was my introduction to Cuba. After I discovered the real Santiago was still, at 102, puffing away on a cigar in his home in Cojimar, broke as I was, I had to go. I didn’t know the first thing about finding Fuentes but my Hungarian-Gypsy mother told me to look up her friends on the island for help. “Which Cuban friends?” I asked skeptically. “How should I know?” she smiled. “I haven’t met them yet. But they’re there.” And, somehow, just like she promised, they were. And these same Cuban friends did help me find him. “Of course we know Gregorio!” (“See!” my mother responded to this fact when I got back home and told her.) The following morning after a modest drive outside of Havana and a knock at the door later he appeared. One my favorite things about the island is the fact that none of the sites to see hold a candle to meeting the Cuban people themselves.

While Hemingway covered every major war during his lifetime, at first I couldn’t understand why he steered clear of the Cuban revolution on his doorstep. Maybe it wasn’t so much a question of what Hemingway would have done with Fidel Castro and the Revolution but what Fidel Castro and the Revolution would have done with Hemingway. Twelve American presidents and hundreds of assassination plots later, a Castro remains in power. On the other hand, maybe Santiago’s story going 84 days without catching a fish and finally catching the biggest of his life only to lose it on the way back to shore tells as much about the Revolution and Cuba’s history as anything that’s been written. From the arrival of Columbus in 1492 all the way to 1959, was certainly felt by most Cubans as a long enough losing streak not to have control of their own country that they overthrew a US-backed dictatorship and handed over the reins of power to a pack of kids. Yet the majority of the Cubans I dealt with over the 11 years I traveled to Havana certainly bore the scars of seeing much of the revolution’s prize chewed up and torn apart over the ensuing decades as Fidel tried to bring it to shore.

Gertrude Stein once mocked Hemingway in her Autobiography of Alice B Toklas that he had “passionately interested rather than interesting eyes.” While much of Hemingway’s acclaim is based on the allure of him having led one of the most interesting lives of the 20th Century, in Cuba at least, their appreciation stems more from the fact he led an even more interested life. Havana has taken full advantage of the fact that America’s if not the world’s most famous writer chose to spend the last two decades of his life in Cuba, the place he felt most at home in the world. He even bestowed the Nobel and Pulitzer prizes on the Cuban people after declaring himself a Cuban. Hemingway and Cuba are and always will be eternally linked.

Gregorio died two years after the only time I met him. His beloved boat Pilar was removed from the sea and deposited next to Hemingway’s swimming pool in San Francisco de Paula. A quaint pet cemetery of cats and dogs is nearby. The house a short path away is a national museum, virtually untouched from the day Hemingway painfully left in 1960. The caricature Hemingway of Woody Allen’s Midnight In Paris has tended to dominate Hemingway’s legacy a great deal in our country. Havana in turn has created a kind of gift shop legacy for Hemingway as well with the bars, hotel rooms, and the marina. As for the magic sprinkled between the pages of The Old Man and the Sea itself? I’m sure if you asked my mother she’d tell you to look up some more of her friends she hasn’t had the chance to meet yet in Havana and they’ll give you a hand finding it.

BRIN-JONATHAN BUTLER is the author of Domino Diaries: My Decade Boxing with Olympic Champions and Chasing Hemingway’s Ghost in the Last Days of Castro’s Cuba. As a writer and filmmaker, his work has appeared in ESPN Magazine, Vice, Deadspin, The Wall Street Journal, Salon, and The New York Times. Butler’s documentary, Split Decision, is Butler’s examination of Cuban-American relations and the economic and cultural paradoxes that have shaped them since Castro’s revolution, through the lens of elite Cuban boxers forced to choose between remaining in Cuba or defecting to America.