by John Suchet

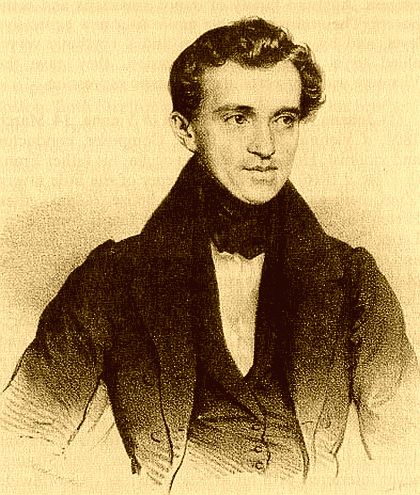

Johann Strauss Journeys to the United Kingdom

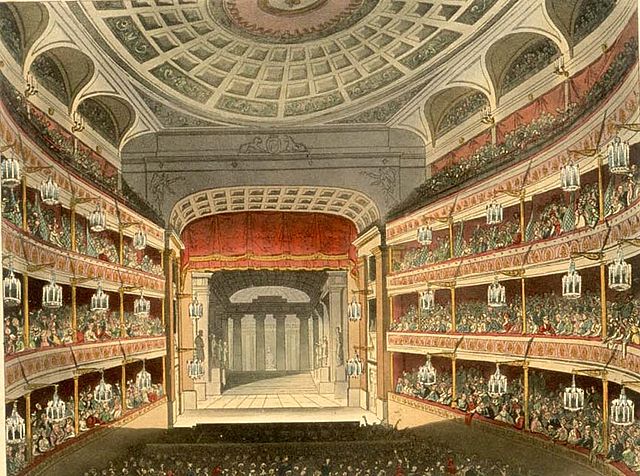

Between that first concert on 17 April 1838 and the end of July, Johann Strauss and his orchestra gave a total of seventy-nine performances in London alone, and the list of hosts for whom he performed reads like a Who’s Who of English aristocracy: the Duke of Wellington, the Duke of Devonshire, the Duke of Cambridge, the Duke of Buccleuch and Sutherland, the Countess of Cadogan and Mrs Lionel de Rothschild, as well as the ambassadors of Austria and France. There were also two public balls, two charity concerts, thirty-nine public concerts, and three large-scale concerts shared with other high-profile artists.

The ultimate accolade, though, came with the invitation to perform in the presence of the young Princess Victoria in Buckingham House, the building she was about to make her official royal palace. This took place on 10 May, and Johann Strauss followed his usual practice of performing a piece specially composed for the occasion. This was the waltz ‘Hommage à la Reine d’Angleterre’, which tactfully quoted from ‘Rule, Britannia’ in its introduction and ‘God Save the Queen’ in waltz tempo in its coda. The Times reported that Strauss’s new waltz was much admired by the future queen, and thereafter Johann Strauss made sure he included it in future performances following the coronation, both at the Palace and elsewhere on tour.

And what a tour he now embarked on. Even while resident in London, Johann Strauss and the orchestra made a five-day visit to Cheltenham and Bath, and on leaving London at the end of July they began a six-week tour of England, Scotland and Ireland. In all they would perform in thirty-one different towns and cities, making return visits by popular demand to several of them.

On many days they gave three performances in three different venues: matinee, late afternoon, and evening. It was reported Johann Strauss could now command fees of £200 or more for a performance – a substantial amount at that time. The constant travel was made easier by advances in modes of transport. Strauss himself wrote of the tour:

“I found myself in a different town almost daily, as one may travel here exceedingly quickly by virtue of the good horses and excellent roads … Of great advantage to the traveler are the railways, which I have used extensively, in Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, etc. …”

But there was one feature of life in the United Kingdom over which Johann Strauss could have no control: the weather. October in Scotland was cold and wet. There was a week of ceaseless rain, coaches had trouble making headway through the mud, and several members of the orchestra came down with colds or worse. A local doctor prescribed a concoction of claret, nutmeg and ginger, ‘hot enough to wake the dead’. Still they performed. It was thus a group of musicians of depleted strength that made the crossing to Ireland, and all the more so on their return.

It was inevitable that sooner or later a work schedule of this intensity would catch up with Johann Strauss and his men. It did so in the north of England. In November Strauss was reported to be suffering from ‘illness of a serious character’. He had severe shivering fits, a hacking cough and chest pains. Concerts in Derby and Leicester were postponed. A doctor in Derby did little to improve things, by prescribing Strauss a dangerously strong dose of opium that almost killed him. It is possible, even probable, that Strauss did not receive much sympathy from his men. This time they really had had enough. They had been away from home now for over a year, and they wanted to return to Vienna. A small but militant clique warned Strauss that if he did not promise that they would leave for home soon, they would refuse to play on.

There was another factor at work here, hidden not so far beneath the surface. The members of the orchestra were well aware of Johann Strauss’s domestic arrangements back home in Vienna. He had a wife and children in the family home on the edge of the Augarten. He also had a mistress and illegitimate children in the apartment he had set up for them near St Stephen’s Cathedral in the center of the city.

Life for Strauss in Vienna was complicated. Life on tour, on the road, was an escape from all that. What if it was his plan, they conjectured, never to return? To stay away on tour for year after year. And how could he achieve that? Simple. By putting into action a plan he had mentioned more than once: the ultimate ambition. Board a ship for the United States. Succeed there, and there would be no need ever to return to Vienna and all the complications it held for him. Had he not implied as much when they were on tour in Ireland? Look west, he had told them, there is nothing between here and America. That is where we must go.

Johann Strauss knew about the mutterings. He had a few faithful members of the orchestra who reported to him every nuance of what was being said. He also knew that, however much not returning to Vienna would solve domestic issues for him, he had no choice but to go back. He could not abrogate his responsibilities totally.

There was also the question of his health. He needed to consult with doctors who knew him and with whom he could at least converse in his own language. This latest bout of ill health had scared him. When the postponed concerts in Derby and Leicester had eventually taken place, he only had the strength to conduct the first half. That had not happened before. Something had to give.

It was therefore a relieved orchestra that was told by Johann Strauss that the tour was over and they would cross to Calais on the first leg of the return journey to Vienna. This they did on 2 December, almost eight months after arriving in England and fourteen months after leaving Vienna. Strauss was not finished yet, though. It must have taken some persuasion on his part, and probably promises of increased remuneration, but he somehow managed to secure his orchestra’s agreement to give a farewell concert in the rooms of the Philharmonic Society in Calais.

It did not go according to plan. In the third item on the program he collapsed and fell from the podium. There was no swift recovery this time. He was taken to Paris where doctors warned him he needed substantial rest before making another move. He retorted that he was suffering from nothing more than exhaustion, and that after a few weeks of rest and recuperation he would be well enough to resume concerts – right there in Paris.

Reality dawned when he was informed that his orchestra was miles away, well advanced on their return to Vienna. This time, for the first time, he was no longer in control. Nor was his health improving. He lapsed into delirium several more times but was able to make it clear that he wished to return to Vienna to see his own doctors. There was agreement over this, not least because the last thing that the Paris doctors wanted was to preside over the demise of possibly the most famous musician in Europe.

A coach was fitted out with a bed and Johann Strauss began the long journey home. The icy cold December air did nothing to improve his condition and, despite being piled high with blankets, he suffered a relapse in Strasbourg. Eventually the journey continued slowly, passing through Stuttgart, Ulm, Munich, and across the border into Austria. The one orchestral member who had stayed behind to accompany him reported an immediate improvement in his condition when he heard the Austrian accents in the town of Linz on the Danube. He arrived in Vienna three days before Christmas 1838, almost fifteen months since his departure. The Theaterzeitung reported, ‘Strauss has at last arrived in Vienna, but suffering so much that it will be a considerable time before he is fully recovered.’

With typical bravado, even foolhardiness, Johann Strauss was back on the podium two weeks later, on 13 January 1839, at a ball in the Sperl, the dance hall he knew so well. For the occasion – again deploying the tactic at which he was so adept – he performed a piece he had composed specially for the occasion, ‘Freuden-Grüsse (Motto: Überall gut – in der Heimath am besten)’, ‘Joyful Greetings (Motto: Everywhere is good – at home is best)’.

JOHN SUCHET is the author of THE LAST WALTZ:The Strauss Dynasty and Vienna, as well as a well-known journalist and radio presenter in the UK where he presents for Classic FM, the UK’s only 100 per cent classical music radio station. Before turning to classical music, he was one of the UK’s best-known television journalists. He has been named Television Journalist of the Year, Television Newscaster of the Year, and been awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Royal Television Society. He has also been honored by the Royal Academy of music for his work on Beethoven including the internationally bestselling Beethoven: The Man Revealed.