by Stephen Jarvis

Six months ago, if you had asked me about my novel Death and Mr Pickwick, I would probably have said: It is about the dawning of the age of global celebrity and its main characters are Charles Dickens and the artist Robert Seymour. I now believe I have created something else: what might be called ‘the trail novel’. Read it, and you may feel the urge to go to places connected to the novel, to eat and drink there, collect souvenirs, and take a picture.

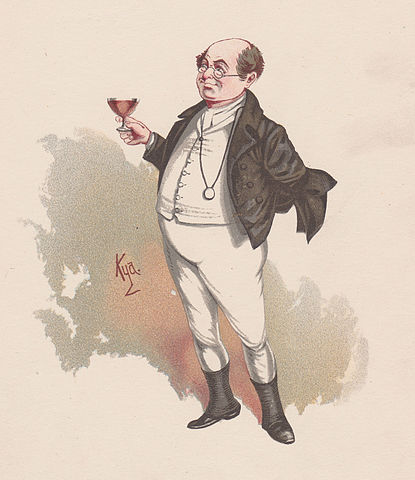

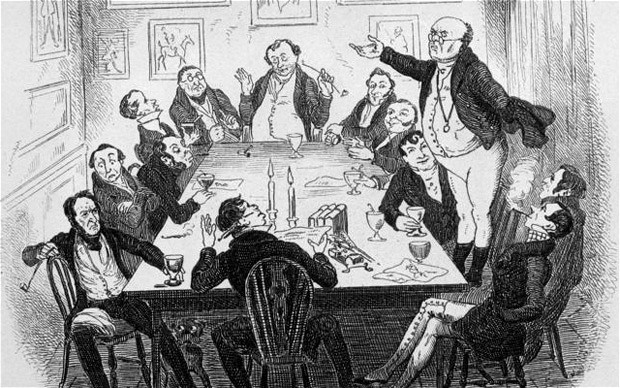

Let me give some background. Charles Dickens’s first novel The Pickwick Papers isn’t widely read these days, but things used to be very different: it was the first literary blockbuster and indeed for almost a century it was the most famous novel in the world. The Pickwick Papers also has, in my view, the greatest backstory of any work of fiction: a backstory of deep tragedy set against colossal triumph, with an extraordinary cast of characters – from a mad alcoholic clown to a wine-merchant with a pet vulture – whose lives are all linked to The Pickwick Papers. The backstory of Pickwick cried out to be turned into a novel itself – so that’s what I did! Do you need to have read The Pickwick Papers before reading Death and Mr Pickwick? No, not all. But if you read my novel, you will soon realize that the story of Pickwick’s creation says a great deal about the making of the modern world, and you may be led to read The Pickwick Papers afterwards. And if you do, that may well be the first stirrings of an urge that will eventually take you on the Death and Mr Pickwick trail. The pleasures of most books end when you reach the last page, but that is not so with Death and Mr Pickwick.

Excerpt from Death and Mr Pickwick – 1797

It was a cold spring Somerset day, shortly after dawn, when Henry Seymour, accompanied by a muscular, ragged-eared bulldog, closed the door of his cottage and proceeded down the path. He passed patches of parsnips, kale and carrots on his way to a wagon, where the horses were already in harness. At least a dozen chairs of diverse sorts were stacked on the vehicle, as well as tables and other items of furniture.

Seymour lifted the dog on to the driver’s seat, then lit his pipe and looked to the cottage once more. At the downstairs window, a trim woman in nightclothes stood between a small boy and a smaller girl, both similarly attired to herself, who had climbed upon the ledge. There were waves. Seymour put his boot upon the foot-board and took up the reins – but just then saw a magpie hopping across the road. The bird paused to stare. As was the tradition, he was about to take off his hat to the magpie, and had raised his hand to the brim, when the woman opened the door and asked Seymour to bring back a quarter of cheese from the market. ‘I was going to,’ he said. He turned back to see the bird fly away, without receiving his due respect.

‘I could have done without that,’ he said to the dog. He pulled down his hat, as if to protect himself from the bird’s omen. The dog suddenly sneezed. ‘Oh, you’re the one who’s cursed,’ he said. ‘Very grateful to you.

But who’ll take on the terriers if you’re sick?’ He flicked the reins, and the horses trotted down the dirt road to Yeovil. At Yeovil market, Henry Seymour’s stall lay between the cheesemonger and a maker of hempen sacks. Here, he folded his arms, and occupied one of the chairs that he had made for sale. Even if the wallet attached to his belt had not bulged, the satisfied expression as he smoked his pipe suggested the state of his finances. ‘Now, now,’ he whispered to the dog at his feet, who twitched an injured ear. ‘Could she be the next? Can we smoke the money out of her purse? What do you think, boy?’

The prospective customer was a middle-aged woman, smartly dressed, but with a badger-like aspect to her face and hair. She carried an edition of Gay’s Fables and a well-preserved copy of the Novelist’s Magazine, which she had just purchased from the second-hand bookstall – which she displayed, to their advantage, in her basket. Stopping at the cheesemonger, she sampled two cheddar-dice, before purchasing half a pound. Seymour puffed harder, and the cloud of his smoke enveloped the woman, and then she smiled at him, and he smiled back, and she ran her eyes over the furniture, fixing upon a chair upholstered in green morocco.

‘Did you upholster this?’ she said. Her accent was Somerset, but there was London in it too.

‘Every horsehair,’ said Seymour.

She sat, and tested the comfort and stood again. ‘Would you turn the seat upside down, please?’ He did so. She examined the webbing.

‘Did you do this as well?’

‘Every tack.’

‘I am tempted’. She stroked the leather once more. ‘It looks as good as anything made by Seddon’s.’

‘And who is he?’

‘Who is he? You have never heard of Seddon’s!’ She laughed, looking around with an air of great worldliness. ‘Well, I am in the country!’ She laughed some more, and away she walked, losing all interest in the furniture, vanishing into the regions devoted to colored threads, ladies’ gloves

and belts.

Henry Seymour continued sitting at his stall, mystified. There was also a lull in trade afterwards, with no further interest expressed in his wares, which was unusual. When his pipe went out – which it was never known to have done on a market day before, without being instantly refilled and re-lit – he said to his dog, ‘That’s it, boy, we ’re not going to sell any more today, I just know it.’ He packed the unsold furniture on to his cart, and set off. As soon as he hit the road, a hare ran in front of his horses, and he cursed it, saying that it was all he needed. Then he added: ‘Damn me, I forgot the cheese. She ’ll make me suffer, but I ain’t going back for it.’

A few miles from home, he stopped at a roadside inn, half hidden behind ivied oaks. He acknowledged the landlord – a man whose profusion of white eyebrows and staring eyes suggested that he had witnessed some terrible incident in the past, and occasionally recalled it – and after taking the first sip of porter, Seymour said: ‘You heard of Seddon’s, Bill?’

‘Seddon’s?’ He wrung out a cloth, till it would surely have screamed, had it been alive. ‘What’s that then?’

‘I’m thinking, to do with furniture.’

A handsome bagman at the end of the bar jutted an excellent chin forward. ‘Seddon’s is furniture – in e-very con-ceiv-able way.’ He lent on the bar, with the easy-going manner of one not being watched by his employer, which all successful commercial travelers can draw upon, as a resource.

‘Seddon’s is the grandest furniture maker in all London. Any sort of furniture, you go to Seddon’s.’ He drew his beer to his lips, and blew off froth, a little of which dripped down over the edge, towards his index finger, where there was a golden ring with a fox’s head.

‘So they make upholstered chairs?’ said Henry Seymour.

‘Anything upholstered. They’ve even got a department in the basement devoted entirely to upholstering one thing – guess what it is.’

‘Sofas.’

‘Coffins. Coffins, I say.’

‘How do you know that then?’ said the landlord. ‘You had a session with a desperate lady in one of ’em?’ he added with a coarse laugh. ‘I know because there ’s a friend of a friend of mine that sells them pillowcases. And I do know my friend’s wife.’ He wiped his fingers, and gave a knowing grin.

‘Do you believe,’ said Seymour tentatively, ‘they would buy furniture made by someone else?’

‘You an upholsterer?’

‘I’m more than that. Seddon’s make any sort of furniture, you say?’

‘Anything.’

‘Then Seddon’s are like me.’

‘Well you’d better go and tell them that, then! You doing well in the furniture business?’

‘Well enough.’

‘Seddon – the man in charge – he ’s worth a fortune. Lost a bit in a fire, I hear, but didn’t stop him. When he passes it all on to his sons, they’ll have a lot to thank their father for.’

Stephen Jarvis was born in Essex, England. Following graduate studies at Oxford University, he quickly tired of his office job and began doing unusual things every weekend and writing about them for The Daily Telegraph. These activities included learning the flying trapeze, walking on red-hot coals, getting hypnotized to revisit past lives, and entering the British Snuff-Taking Championship. Death and Mr. Pickwick is his first novel. He lives in Berkshire, England.