by Philip Jett

Robert Todd Lincoln did not resemble his famous father. At seven inches shorter and quite a few pounds heavier, many who met him were disappointed. He lacked the ability to spin a tale like his father, often referred to as an “unsympathetic bore.” Yet, after his brothers died at ages three, eleven, and eighteen, Robert became the only living legacy of the most popular U.S. president.

Robert attended the finest schools, such as Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard College, and Harvard Law School. By age twenty-one, he’d already attended both of his father’s presidential inaugurations. A year later, he left Harvard Law School to become the assistant adjutant to General Grant, a mere two months before the Civil War ended. He was present during General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. After the war, Robert moved to Chicago and finished school at what is today Northwestern School of Law. He married Mary Eunice Harlan, whose father was a U.S. Senator and Secretary of the Interior. They had two daughters and a son.

Robert attended the finest schools, such as Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard College, and Harvard Law School. By age twenty-one, he’d already attended both of his father’s presidential inaugurations. A year later, he left Harvard Law School to become the assistant adjutant to General Grant, a mere two months before the Civil War ended. He was present during General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. After the war, Robert moved to Chicago and finished school at what is today Northwestern School of Law. He married Mary Eunice Harlan, whose father was a U.S. Senator and Secretary of the Interior. They had two daughters and a son.

Robert was asked to run for president or vice-president several times but refused, although he did accept positions as the U.S. Secretary of War in 1881 and the Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of St. James in 1889. He became a successful corporate lawyer and later became president of the enormous Pullman Palace Car Company, which produced streetcars and luxury railway cars. He and his family traveled the world and owned beautiful homes, including the twenty-four room mansion, Hildene, with eight bathrooms, eight fireplaces, and a basement, on 400-acres in Manchester, Vermont. Quite an improvement over his father’s childhood log cabin.

Yet sadness also followed Robert. He’d lost his father to an assassin’s bullet when he was twenty-one years old. His only son, Abraham “Jack” Lincoln II, died at the age of sixteen of a blood infection. His mother’s notoriously odd behavior grew more bizarre so Robert committed her to a private sanitarium for women. She eventually lived out the remainder of her life quietly with a sister in Illinois. Her relationship with Robert never recovered.

Yet sadness also followed Robert. He’d lost his father to an assassin’s bullet when he was twenty-one years old. His only son, Abraham “Jack” Lincoln II, died at the age of sixteen of a blood infection. His mother’s notoriously odd behavior grew more bizarre so Robert committed her to a private sanitarium for women. She eventually lived out the remainder of her life quietly with a sister in Illinois. Her relationship with Robert never recovered.

Uncannily, Robert was associated with each of the first three presidential assassinations. He’d eaten breakfast with his father, but refused his mother’s invitation to join them at Ford’s Theatre that evening, preferring to stay at the White House instead. When Robert received word of the shooting, he rushed to his father’s bedside at the Petersen House and wept there until his father succumbed.

While serving as Secretary of War in 1881, he accompanied President James Garfield to the Sixth Street Train Station in Washington, D.C. where he witnessed the shooting of the president. “How many sorrows have I passed in this town?” he said. Twenty years later, he accepted the invitation of President William McKinley to attend the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, where McKinley was shot as Robert made his way through the Exposition to join him. Feeling cursed, Robert refused subsequent presidential invitations, once writing: “No, I’m not going . . . because there is a certain fatality about presidential functions when I am present.”

No event exemplifies Robert’s blessed and cursed life more than one that took place in 1864 on a New Jersey railway station platform. Years later, Robert recalled the incident: “The train began to move, and by the motion, I was twisted off my feet . . . and was personally helpless, when my coat collar was vigorously seized and I was quickly pulled up and out to a secure footing on the platform. Upon turning to thank my rescuer, I saw [the gentleman], whose face was of course well known to me, and I expressed my gratitude to him.” A member of General Grant’s staff wrote a letter to that gentleman expressing President Lincoln’s gratitude, something the man kept and displayed often. The gentleman was the famous actor, Edwin Booth, brother of John Wilkes Booth, who would assassinate Robert’s father months later.

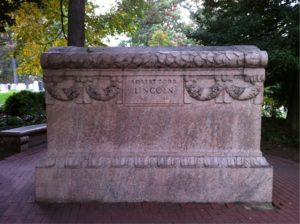

Robert made his last public appearance at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. in May 1922. He died at Hildene four years later, one week shy of his eighty-third birthday. Though he desired to be buried in the Lincoln Tomb in Springfield, Illinois, his wife interred him in a grand sarcophagus at Arlington Cemetery.

Robert made his last public appearance at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. in May 1922. He died at Hildene four years later, one week shy of his eighty-third birthday. Though he desired to be buried in the Lincoln Tomb in Springfield, Illinois, his wife interred him in a grand sarcophagus at Arlington Cemetery.

Many might say Robert Lincoln became a millionaire off of his father’s presidency and assassination and achieved little in the way of public service. He was anti-labor and did not stand up against discrimination. Instead, he felt comfortable steering the high-paying helm of the largest manufacturing company in America at the turn of the century. Yet, it is hard to criticize the son of Abraham Lincoln. He had some mighty big shoes to fill—size 14 as a matter of fact.

PHILIP JETT is a former corporate attorney who has represented multinational corporations, CEOs, and celebrities from the music, television, and sports industries. He is the author of The Death of an Heir: Adolph Coors III and the Murder That Rocked an American Brewing Dynasty. Jett now lives in Nashville, Tennessee.