By Anna Reid

This is the story of the siege of Leningrad, the deadliest blockade of a city in human history. Leningrad sits at the

north-eastern corner of the Baltic, at the head of the long, shallow gulf that divides the southern shores of Finland from those of northern Russia. Before the Russian Revolution it was the capital of the Russian Empire, and called St Petersburg after its founder, the tsar Peter the Great. With the fall of Communism twenty years ago it regained its old name, but for its older inhabitants it is Leningrad still, not so much for Lenin as in honour of the approximately three-quarters of a million civilians who starved to death during the almost nine hundred days – from September 1941 to January 1944 – during which the city was besieged by Nazi Germany. Other modern sieges – those of Madrid and Sarajevo – lasted longer, but none killed even a tenth as many people. Around thirty-five times more civilians died in Leningrad than in London’s Blitz; four times more than in the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima put together.

On 22 June 1941, the midsummer morning on which Germany attacked the Soviet Union, Leningrad looked much the same as it had done before the Revolution. A seagull circling over the gilded needle of the Admiralty spire would have seen the same view as twenty-four years previously: below the choppy grey River Neva, lined by parks and palaces; to the west, where the Neva opens into the sea, the cranes of the naval dockyards; to the north, the zigzag bastions of the Peter and Paul Fortress and grid-like streets of Vasilyevsky Island; to the south, four concentric waterways – the pretty Moika, coolly classical Griboyedov, broad, grand Fontanka and workaday Obvodniy – and two great boulevards, the Izmailovsky and the Nevsky Prospekt, radiating in perfect symmetry past the Warsaw and Moscow railway stations to the factory chimneys of the industrial districts beyond.

Appearances, though, were deceptive. Outwardly, Leningrad was not much altered; inwardly, it was profoundly changed and traumatised. It is conventional to give the story of the blockade a filmic happy-sad-happy progression: the peace of a midsummer morning shattered by news of invasion, the call to arms, the enemy halted at the gates, descent into cold and starvation, springtime recovery, victory fireworks. In reality it was not like that. Any Leningrader aged thirty or over at the start of the siege had already lived through three wars (the First World War, the Civil War between Bolsheviks and Whites that followed it, and the Winter War with Finland of 1939–40), two famines (the first during the Civil War, the second the collectivisation famine of 1932–3, caused by Stalin’s violent seizure of peasant farms) and two major waves of political terror. Hardly a household, particularly among the city’s ethnic minorities and old middle classes, had not been touched by death, prison or exile as well as impoverishment. For someone like the poet Olga Berggolts, daughter of a Jewish doctor, it was not unduly melodramatic to state that ‘we measured time by the intervals between one suicide and the next’.¹ The siege, though unique in the size of its death toll, was less a tragic interlude than one dark passage among many.

The tragedy arose from the combined hubris of Hitler and Stalin. In August 1939 they had astonished the world by putting ideology aside to form a non-aggression pact, under which they divided Poland between them. When Hitler turned on France the following spring Stalin stood aside, continuing to supply his ally with grain, metals, rubber and other vital commodities. Though it is clear from what we now know of Stalin’s conversations with his Politburo that he expected to be forced into war with Germany sooner or later, the timing of the Nazi attack – code-named Barbarossa or ‘Redbeard’ after a crusading Holy Roman Emperor – came as a devastating shock. The new, poorly defended border through Poland was overrun almost immediately, and within weeks the panic-stricken Red Army found itself defending the major cities of Russia herself.

Chief victim of this unpreparedness was Leningrad. Immediately pre-war, the city had a population of just over three million. In the twelve weeks to mid-September 1941, when the German and Finnish armies cut it off from the rest of the Soviet Union, about half a million Leningraders were drafted or evacuated, leaving just over 2.5 million civilians, at least 400,000 of them children, trapped within the city. Hunger set in almost immediately, and in October police began to report the appearance of emaciated corpses on the streets. Deaths quadrupled in December, peaking in January and February at 100,000 per month. By the end of what was even by Russian standards a savage winter – on some days temperatures dropped to -30°C or below – cold and hunger had taken somewhere around half a million lives. It is on these months of mass death – what Russian historians call the ‘heroic period’ of the siege – that this book concentrates. The following two siege winters were less deadly, thanks to there being fewer mouths left to feed, and to food deliveries across Lake Ladoga, the inland sea to Leningrad’s east whose south-eastern shores the Red Army continued to hold. In January 1943 fighting also cleared a fragile land corridor out of the city, through which the Soviets were able to build a railway line. Mortality nonetheless remained high, taking the total death toll to somewhere between 700,000 and 800,000 – one in every three or four of the immediate pre-siege population – by January 1944, when the Wehrmacht finally began its long retreat to Berlin.

Remarkably, the siege of Leningrad has been paid rather little attention in the West. The best-known narrative history, written by Harrison Salisbury, a Moscow correspondent for the New York Times, was published in 1969. Military historians have concentrated on the battles for Stalingrad and Moscow, despite the fact that Leningrad was the first city in all Europe that Hitler failed to take, and that its fall would have given him the Soviet Union’s biggest arms manufacturies, shipyards and steelworks, linked his armies with Finland’s, and allowed him to cut the railway lines carrying Allied aid from the Arctic ports of Archangel and Murmansk. More generally, the siege remains lost in the gloomy vastness of the Eastern Front – an empty, snow-swept plain, in the public imagination, across which waves of Red Army conscripts stumble, greatcoats flapping, towards massed German machine guns. Worryingly often, during the writing of this book, friends turned out to think that Leningrad (on the Baltic, now called St Petersburg) and Stalingrad (a third of the size, near the present-day border with Kazakhstan, now called Volgograd) were actually the same place.

A slightly different form of vagueness afflicts Germans, for whom the Eastern Front was regarded until recently as a scene of military suffering rather than atrocity. Millions of Germans have to live with the fact that a parent or grandparent was a member of the Nazi Party; millions more have a father or grandfather who fought in Russia. It is easier to remember that they were frostbitten and frightened, or starved and put to forced labour in prisoner-of- war camps (almost four in ten of the 3.2 million Axis soldiers taken prisoner by the Soviets died in captivity²), than that they burned villages, stripped peasants of winter clothing and food, and helped round up and shoot Jews. More broadly, Leningrad cedes in the guilt stakes to the Holocaust: ‘To be cynical’, says one German historian, ‘we have so many problematic aspects to our history that you have to choose.’³ Strolling around the lovely medieval city of Freiburg, home to Germany’s military archives, one comes across small brass plaques, engraved with names and dates, set into the pavement. They mark the houses from which local Jewish families were deported to the concentration camps. Leningrad’s women and children, murdered by the same regime with equal deliberation, suffered out of sight and to this day largely out of mind.

The other reason the siege has been little written about, of course, is that the Soviets made it impossible to do so truthfully. During the war, censorship was all-pervading. Russians outside the siege ring, let alone Westerners, had only the vaguest idea of conditions inside the city. Soviet news broadcasts admitted ‘hardship’ and ‘shortage’ but never starvation, and Muscovites were amazed and horrified at the accounts privately given them by friends who made it out across Lake Ladoga. British and American media parroted the Soviet news bureaux. As the initial battles for Leningrad drew to stalemate the BBC’s reports tailed off , and a year later London’s Times reported the establishment of a land corridor out of the city with massive, unconscious understatement. Leningraders, readers were told, had suffered ‘fearful privations’ during the first siege winter, but with the coming of spring conditions had ‘at once improved’. Allied officialdom was equally in the dark. A member of Britain’s wartime Military Mission to Moscow, a young naval lieutenant at the time, recounts how his only source of information was an actress friend, who got food to her besieged parents by begging a seat on a general’s aeroplane.

After the war, the Soviet government admitted mass starvation, citing a spuriously precise death toll of 632,253 at the Nuremberg war crime trials. Honest public description of its horrors, however, remained off-limits, as did all debate over why the German armies had been allowed to get so far, and why food supplies had not been laid in, nor more civilians evacuated, before the siege ring closed. The boundaries narrowed even further with the onset of the Cold War and with Stalin’s launch, in 1949, of two new purges. The first, carried out in secret, swept up Leningrad’s war leadership and Party organisation; the second, against ‘cosmopolitanism’ – codeword for Jewishness or any sort of perceived Western leaning – hundreds of its academics and professionals. The same year one of Stalin’s cronies, Georgi Malenkov, visited the popular Museum of the Defence of Leningrad, which housed home-made lamps and a mock-up of a wartime ration station (complete with two thin slices of adulterated bread) as well as quantities of trophy ordnance. Striding furiously through the halls, he is said to have brandished a guidebook and shouted: ‘This pretends that Leningrad suffered a special “blockade” fate! It minimizes the role of the great Stalin!’, before ordering the museum’s closure. Its director was accused of ‘amassing ammunition in preparation for terrorist acts’ and sentenced to twenty-five years in the Gulag.

With Stalin’s death in 1953 and Nikita Khrushchev’s rise to power, it finally became possible to focus on aspects of the war other than the Great Leader’s military genius. As well as Khrushchev’s ‘Secret Speech’ denouncing Stalin’s Party purges, and the publication of Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, the ‘Thaw’ saw the opening, in 1960, of the first memorial complex to Leningrad’s civilian war dead. The site chosen was the Piskarevskoye cemetery in the city’s north-eastern suburbs, site of the largest wartime mass graves. Khrushchev’s successor Leonid Brezhnev went further, making the siege one of the centrepieces of a new cult of the Great Patriotic War, designed to distract from lagging living standards and political stagnation. Leningraders, in this version, turned from victims of wartime disaster to actors in a heroic national epic. They starved to death, true, but did so quietly and tidily, willing sacrifices in the defence of the cradle of the Revolution. Nobody grumbled, shirked work, fiddled the rationing system, took bribes or got dysentery. And certainly nobody, except for a few fascist spies, hoped the Germans might win.

The final point of retelling the story of the siege of Leningrad, though, is not to restore to view an overlooked atrocity, strip away Soviet propaganda or adjust the scorecards of the great dictators. It is, like all stories of humanity in extremis, to remind ourselves of what it is to be human, of the depths and heights of human behaviour. The siege’s most eloquent victims – the diarists whose voices form the core of this book – are easy to relate to. They are not faceless poor-world peasants but educated city-dwelling Europeans – writers, artists, university lecturers, librarians, museum curators, factory managers, bookkeepers, pensioners, housewives, students and schoolchildren; owners of best coats, gramophones, favourite novels, pet dogs – people, in short, much like ourselves. Some did turn out to be heroes, others to be selfish and callous, most to be a mixture of both. As a memoirist puts it of the Party representatives in her wartime military hospital, ‘There were good ones, bad ones, and the usual.’ Their own words are their best memorial.

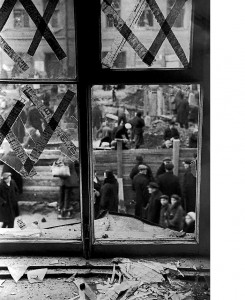

Communism’s collapse twenty years ago made it possible, in the words of one Russian historian, to start ‘wiping off the syrup’. Government archives opened, giving access to internal Party memos, security service reports on crime, public opinion and the operations of various government agencies, the case files of political arrestees, political officers’ despatches from the front, and transcripts of telephone calls between the Leningrad leadership and the Kremlin. Literary journals began publishing unexpurgated siege memoirs and diaries, and newspapers outspoken interviews with still-angry Red Army veterans and siege survivors. Not least, a great many photographs were published for the first time – not of smiling Komsomolkas with spades over their shoulders, but of stick-legged, pot-bellied children, or messy piles of half-naked corpses.

Though gaps remain – some material is still classified; some was destroyed during the post war purges – the new material leaves Brezhnev’s mawkish fairytale in tatters. Yes, Leningraders displayed extraordinary endurance, selflessness and courage. But they also stole, murdered, abandoned relatives and resorted to eating human meat – as do all societies when the food runs out. Yes, the regime successfully defended the city, devising ingenious food supplements and establishing supply and evacuation routes across Lake Ladoga. But it also delayed, bungled, squandered its soldiers’ lives by sending them into battle untrained and unarmed, fed its own senior apparatchiks while all around starved, and made thousands of pointless executions and arrests. The camps of the Soviet Gulag, the historian Anne Applebaum remarks, were apart from, but also microcosms of, life in the wider Soviet Union. They shared ‘the same slovenly working practices, the same criminally stupid bureaucracy, the same corruption, and the same sullen disregard for human life’.7 The same applies to Leningrad during the siege: far from standing apart from the ordinary Soviet experience, it reproduced it in concentrated miniature. This book will not argue that mass starvation was as much the fault of Stalin as of Hitler. What it does, however, conclude is that under a different sort of government the siege’s civilian (and military) death tolls might have been far lower.

For many Russians, this is hard to swallow. There is not much to celebrate in Russia’s twentieth-century history, and the victory over Nazi Germany is a justified source of pride and patriotism. When Vladimir Putin, like Brezhnev before him, lays on lavish wartime anniversary celebrations, he finds a receptive audience. An element of tactful self-censorship also comes into play, because as well as flattering the regime the heroicised Brezhnevite version of the siege eased trauma for survivors. It is hard – cruel even – to cast doubt on the doughty old woman kind enough to give an interview when she describes neighbours helping each other out, mothers sacrificing themselves for children, or good care in an evacuation hospital. She is not propagandizing or myth-building, but has constructed a version of the past that is possible to live with. Paradoxically, public discussion of the blockade is likely to become franker once the last blokadniki have passed away.

Excerpted from Leningrad: Tragedy of a City under Siege, 1941-44, by Anna Reid.

ANNA REID was born in 1965, read law at Oxford and Russian History at UCL’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies. She started her career in consultancy and business journalism; from 1993 to 1995 she lived in Kiev, working as Ukraine correspondent for the Economist, and from 2003 to 2007 ran theforeign affairs programme at the think-tank Policy Exchange. She lives in west London.

Leningrad, published by Bloomsbury in September 2011, follows the three-year siege of Leningrad during World War II.