by Marc Aronson and Marina Budhos

ON THE LEFT BANK of the Manzanares River , the scrub grass is stiff with frost. Capa, Regler, and an officer peer across the water, trying to make out the enemy’s position. The three are in the northwest corner of the city, in a group of farm buildings belonging to the agricultural school in University City. Franco’s troops have already crossed the river on footbridges, stationed themselves in the School of Architecture, and are now in a large manor, the Palacio de la Moncloa. This stretch of campus is no-man’s-land. Somewhere in these abandoned horse stables and granaries, the invisible enemy lies in wait. Capa follows the men into rooms fortified with sandbags, then through an old slaughterhouse, where the soldiers tilt their rifles through broken patches in the wall.

A scout arrives to tell them that Moroccans are on the top floor of a barn, shooting through holes in the floor and killing government soldiers. Suddenly, a burst of shelling breaks out, and the three men dive to the ground. Bullets whistle and screech overhead. “You’ve got me trapped by the Moors!” Capa shouts, half-frightened, half-joking to Regler.

When the shooting stops and the three men get up, a shaken Capa asks to pause, having soiled his pants. “My intestines were not so brave as my camera,” he jokes.

THE CRUEL SKY

Capa spends the next couple of weeks covering the fighting in University City. He takes moody, smoky shots in old medical school classrooms, where barricades have been constructed out of suitcases and stacks of textbooks. It’s as if the battle in University City were a war for knowledge itself: laboratories are described by one reporters as having “delicate scientific instruments crushed under fallen bricks, . . . notebooks and specimens strewn among shattered furniture, microscope slides on broken floors, the splintered glass starred like crazy paving.”

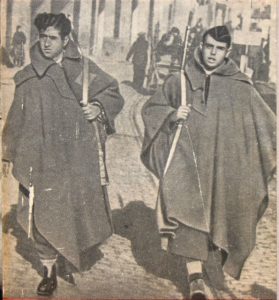

Capa also provides a glimpse of the boredom and waiting that so characterizes war: men playing cards, writing letters, camping out, and eating in an old physics laboratory. Many of the soldiers are from the International Brigades, and inside the old classrooms, men of all different nationalities break stale bread together, huddle in the chilly outposts, and shout orders in a mix of languages.

As November turns icy cold, and a dirty fog envelops the city, fighting around University City intensifies. House to house, floor to floor, the men clash, battling at times for a full twenty-four hours a day. Franco’s troops capture more buildings. Government losses are heavy—beloved anarchist leader Buenaventura Durruti, who brought three thousand troops from Aragon, is shot and killed. And ye t the rebels do not break through the front lines; the city has not fallen to the fascist assault.

t the rebels do not break through the front lines; the city has not fallen to the fascist assault.

Over the next few weeks, Capa photographs battle scenes and the city of Madrid itself, along with its resident Madrileños. Nightly they huddle, listening to buildings “quiver,” watching the electricity blink on and off. Outside the windows covered in blackout curtains come the hiss and boom of explosions and ghoulish shadows cast on the streets and canyons of walls. Flimsy buildings, largely in the poorer areas, collapse like children’s toy houses. Never has a city been subjected to such brutal bombing. These bombardments are meant not only to destroy houses but to beat down the spirit of the people in Madrid.

The sky, the terrible and cruel sky, is raining bombs as Franco maintains his aerial assault. In Capa’s photos, we see so many faces, tipped upward, hearing the low hum of motors, scanning for the telltale signs of airplanes. We see, too, families crouched and huddled on the cold concrete floors of subway stations, where they have fled for shelter, with pots, bottles, and blankets gathered around them. The ground overhead thuds and booms; the children laugh and play. We see the exposed innards of buildings, a lone iron bed frame under a wrecked roof.

Anyone who can be spared from the fighting leaves Madrid. Every day fifteen thousand women and children are evacuated from the city. A proud capital has become an endless caravan of refugees, standing beside their bedding or striding away with several chairs slung over a shoulder.

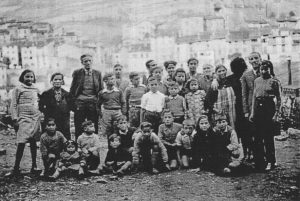

Capa—along with Chim and eventually Taro—is inventing a new visual language, one that shows what it is to lose everything, to be in flight, to be a refugee. One day you are eating soup at your table; the next you are dragging a rolled-up mattress and a few belongings down a street, homeless. Capa and the others are drawn to these images, these stories. While Capa photographs destruction in the making, Chim shows where the refugees flee to—a hastily assembled camp in the stony hills of Montjuïc, near Barcelona. There thousands try to continue some semblance of normality. Chim photographs them lovingly: a frightened girl with a satin bow in her hair sits tentatively on her metal bed, a doll on each knee; mothers pin laundry in the warm sun; a young woman pens a letter atop her suitcase.

This is what Capa, Taro, and Chim are too: refugees, exiles, living on their wits, with no real home. Capa does not even have a passport or official papers anymore—he is not Hungarian, not German, not French—just a man with a camera in the midst of war. That rootless condition is rapidly becoming the condition of thousands in Spain. It’s as if these photographs are a warning: millions will be driven from their homes across the whole continent of Europe if the world does not do something now.

This is what war looks like, his photographs seem to say. This is what happens when we leave Spain to be pummeled by fascists.

Marc Aronson and Marina Budhos are writers whose first joint book was the acclaimed Sugar Changed the World. Aronson is a passionate advocate of nonfiction and the first winner of the Robert F. Sibert Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction. Budhos writes fiction and nonfiction for adults and teenagers, including the recently published Watched. Aronson is a member of the faculty in the Master of Information program at Rutgers and Budhos is a professor of English at William Paterson University. They live with their two sons in Maplewood, NJ.