by Rebecca Fraser

Although the Mayflower’s crew were experienced sailors—Captain Jones had spent a lifetime transporting wine, while the two pilots or mates, John Clarke and Robert Coppin, had previously been to Virginia and New England—Jones had never travelled beyond Europe and he became alarmed by the huge waves, roaring breakers and shoals between Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard. Instead of continuing south towards Virginia, he decided it was safer to turn the ship around and sail back up the coast to Cape Cod. Where Provincetown now stands on a slender peninsula curved around like a lobster claw, the Mayflower made anchor at sunrise on 11 November 1620, after just over two months at sea.

William Bradford remembered that the whole congregation, including Elizabeth and Edward [Winslow], knelt in prayer at having arrived at all. But for all their feelings that God had saved them, the congregation were half-starved. Those who ran ashore and gobbled green mussels contracted food poisoning. The ship’s sanitation, always unsatisfactory, was even more of a health hazard at anchor.

Provincetown had trees, which were reassuring to see. The same species as back home grew around the bay in a harmonious way. There were oaks, pines, and sassafras—nowadays the chief ingredient of root beer, but then reputed a medicine—and other sweet wood. Juniper was cut down and taken back to be burnt on deck to fumigate the ship and cheer the weaker passengers shivering with the cold and incessant damp. Two days after the Mayflower had landed, the women felt brave enough to disembark. They washed themselves and some of their clothes on the beach in a discreet fashion, holding up towels with relief at having some privacy and being clean at last (which, Bradford remarks in a down-to-earth way, was very much needed).

There was, however, the real problem of order with some of the ‘strangers’ who had come on board at Southampton. They did not share the Leiden church’s unifying sense of purpose. There were mutinous mutterings that since they were not within Virginia, they had no patent and were not bound by anyone or anything. They said, accurately, that when ashore they could do as they pleased. No one could command them.

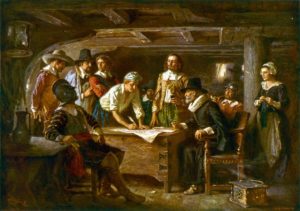

The Pilgrims’ initial problems about permission to depart meant their new colony did not have the advantage of a royal charter. Therefore just before they landed, they decided that they had to draw up an agreement so that everyone would abide by the same laws, which included many of John Robinson’s suggestions. This is now known as the Mayflower Compact. By and large the colonists were sensible people who obeyed the rules and accepted that the energetic Myles Standish should be their military leader, as it was obvious that discipline might be needed at first—authority had to be laid down or the colony would not last. Some of their new companions—especially the chaotic, boisterous Billington family and their ringleader, the obstreperous John Billington—were an argumentative and easily aggrieved group, who were perpetually discontented. One Billington son, the mischievous fourteen-year-old Francis, almost killed some of the passengers when he set off his father’s gun inside a cabin full of people. luckily no one was hurt. Billington’s troublemaking and his refusal to obey Standish’s orders made John Carver, in many ways the kindliest soul imaginable, lose his temper. Billington was called before the whole company and condemned to having his neck and heels roped together in a humiliating fashion until he begged for mercy and was forgiven. Bradford described Billington as ‘a knave’.

The Mayflower Compact shows that the more educated—including Brewster, Carver, and Edward—had some understanding of early seventeenth-century social-contract theory. So long as they were adults, i.e. twenty-one, all males on board were allowed to sign it, including the indentured servants. It bound these forty-one people into ‘a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience’. There was no necessity to be a member of the leiden church.

The Mayflower Compact has been much romanticized. The signing took place in no special cabin. It is unlikely that women or children were present for it, as many representations suggest. Yet artists are right to depict the scene as a moment of great drama and historical import. The act of creating such a colony was revolutionary. Plymouth Colony was the first experiment in consensual government in Western history between individuals with one another, and not with a monarch. The colony was a mutual enterprise, not an imperial expedition organized by the Spanish or English governments. In order to survive, it depended on the consent of the colonists themselves. Necessary in order to bind the community together, it was revolutionary by chance.

The Mayflower Compact has a whisper of the contractual government enunciated in the 4 July 1776 Declaration of Independence, that governments derive their just powers ‘from the consent of the governed’. It anticipated the eighteenth-century American Republic’s belief that political authority was not bestowed by a monarch but a contractual agreement of free peoples, articulated at the end of the seventeenth century by the philosopher John Locke. The eminent American historian George Bancroft has called the Compact ‘the birth of constitutional liberty . . . in the cabin of the Mayflower humanity recovered its rights and instituted government on the basis of “equal laws” for the general good’.

These ideas were not hashed about all the time in the community. They were simply a consequence of their endeavor. But of course, since the Pilgrims were interested in political concepts, devising the rules by which they were to be governed was extraordinarily empowering, especially after all they had suffered. Once the rules were established, the decision-making powers of ordinary people were validated as a way of life.

REBECCA FRASER, daughter of noted British historian Lady Antonia Fraser, is the author of The Story of Britain, which has been described as “an elegantly written, impressively well-informed single-volume history of how England was governed during the past 2000 years.” A reviewer and broadcaster, her previous work also includes a biography of Charlotte Brontë which examined her life within the framework of contemporary attitudes to women. Rebecca Fraser was President of the Brontë Society for many years.