by Kevin R. C. Gutzman

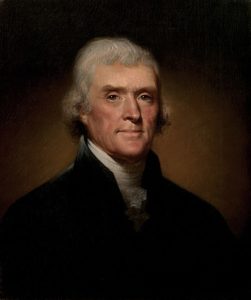

Thomas Jefferson’s influence on American political history outstrips that of any other figure. Only Franklin Roosevelt rivaled President Jefferson’s dominance of the federal government, and Jefferson was more than the supreme politician of the revolutionary era: he was its symbol, even in his own day.

George Washington became the symbol of the Continental Army and of American patriotism, even American nationhood, but Jefferson stood for the principles with which the American Revolution was synonymous: the equality of man, liberty of conscience, and republican self-government. His diplomatic masterstroke, the Louisiana Purchase, and its implementing initiative, the Voyage of Discovery (aka the Lewis and Clark Expedition), made America a continental republic.

That America would be a continental colossus seems a logical outcome of what Jefferson and his contemporaries did. They set the stage for American economic, cultural, military, and legal influence to reach into every corner of the globe. Yet, let us resist the impulse to think that what came after resulted inevitably from what happened in Jefferson’s day. While he expected much of what we know, other aspects of contemporary life would thrill, shock, exasperate, disappoint, invigorate, amaze, or horrify him.

Historians commonly find it surprising that when Jefferson sketched his grave marker, he omitted that he had been governor of Virginia, secretary of state, vice president, and president. In our day, holding such offices is taken as a great accomplishment in itself. Jefferson had a different understanding. He once talked a prominent American scientist out of forsaking science for politics, arguing that America had only one Ben Franklin and only one man like his correspondent, and it would be a shame for such people to leave science. After all, any reasonably bright man could be a politician.

Jefferson did more than merely hold offices, however. The marks of his statesmanship are with us all over America, every day. Those coins in your pocket, representing various numbers of hundredths of a dollar, reflect Jefferson’s proposal of a decimal-based coinage—the world’s first. All over the world, other countries have followed the American example on this score; in living memory, even the United Kingdom finally yielded to the American example.

So too the upper house of your state legislature is likely called a “senate,” as is the upper house of the US Congress, after Jefferson’s 1776 proposal for Virginia’s upper house. Student of ancient history that he was, he thought it obvious that the colonial “council” had to go.

While Jefferson served as American minister to France in the 1780s, lawmakers back home in Richmond (which the General Assembly had designated to replace Williamsburg as the state capital at Jefferson’s suggestion) thought to build a new state capitol. Jefferson insisted they not just throw up a Georgian rectangular building, but instead use the pattern of a Roman temple in the South of France which he had learned to love. Greco-Roman architecture, it seemed to Jefferson, combined concern with beauty with proportion, form, and stateliness in just the way that would encourage republican citizens to comport themselves in a republican fashion. Persuaded, the General Assembly let Jefferson himself draw up the building’s architectural plans. Somewhat expanded to accommodate modern government, Jefferson’s Virginia capitol sits on the bank of the James River even now.

When he became secretary of state in 1790, Jefferson unexpectedly found himself in a position to help shape the layout of the federal capital and the architecture of its first government buildings. Like Virginia’s, they would have classical architectural elements. Today, the same is true of many state government public buildings as well.

The Virginia capitol serves as the seat of the Old Dominion’s republican government, the government of an independent state since May 15, 1776. The rest of the original thirteen joined Virginia in independence on July 4, and they did so by adopting a declaration “&c.” written chiefly by Jefferson. Jefferson described that document at the time as laying out his political creed. Much of American political history since his day concerns the ways and extent to which Americans should understand Jefferson’s creed as our common creed. Jefferson struggled with those questions virtually to his last day. He chose to claim authorship of the Declaration of Independence as his own feat on the aforementioned gravestone. In doing so, he claimed the associated authority for himself as well.

Jefferson hoped to see America adopt a lasting federal union. A commonplace among nationalist historians and commentators says that the US Constitution is better for his absence from the country at the time of its drafting and ratification, as well as the drafting of its first ten and twenty-seventh amendments. How his presence in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 and/or in New York in 1789 would have affected those events will forever be unknown, but some light is shed upon the matter by Jefferson’s work in drafting state constitutions for his home state in 1776.

Jefferson’s draft constitutions began with a preamble laying out the philosophical and historical grounds of the Old Dominion’s break with King George III. That section mirrored the first two sections of the Declaration of Independence, which he was drafting at the same time. It also featured population apportionment of both houses of the state legislature, which Jefferson hoped to see replace the geographic apportionment Virginia had borrowed from English practice. The omission of this practice by the Virginia Convention led Jefferson to favor revision of Virginia’s state constitution for the rest of his life.

As a state legislator, Jefferson led the way in abolition of the feudal land tenures, primogeniture and entail, which had perpetuated a very small aristocracy’s ownership of approximately two-thirds of the land in today’s Virginia throughout the colonial period. In their place, Jefferson persuaded the General Assembly to establish the principle that all children, including females, would inherit equally in cases in which the deceased did not leave a will. Jefferson thought that equalized land ownership would buttress the egalitarian republic he wanted Virginia to become. Jefferson considered his land reforms as basic to his program, and their effects indeed pervaded Virginia society even in his own lifetime.

With that in mind, Jefferson included a constitutional provision that any “person” (again not specifically male) who did not own fifty acres of land and had not owned that amount should be given that allotment out of the public lands. Additionally, he would have extended the suffrage beyond those meeting the colonial property qualifications to all taxpayers.

Jefferson from his teens had been up to speed with the latest currents in European thought. Among the European ideas that appealed to him was Cesare Beccaria’s notion that punishments ought to be proportionate to crimes. Where English law in the 1770s provided death as the penalty for virtually any crime, Beccaria held that the most severe punishment should be for the worst crimes and that the severity of the punishment ought to decline as the crime became less significant. Jefferson proposed a Bill to Apportion Crimes and Punishments in 1779, but it ultimately ran aground on the House of Delegates’ insistence that horse thieves suffer death. In time, however, Jefferson’s position would prevail—in Virginia and elsewhere.

KEVIN R. C. GUTZMAN, JD, PhD, is author of James Madison and the Making of America. Professor of History at Western Connecticut State University and a faculty member at LibertyClassroom.com, he is the author of several books, including best-sellers, has published in all the leading history journals, and writes and speaks frequently for popular audiences. He lives with his son in Connecticut.