by Matthew Dennison

Every Tolkien fan remembers Lobelia Sackville-Baggins. Rapacious, uppity, with a formidable temper and a keen eye for desirable possessions, Lobelia is among the terrors of the Shire. Married to Bilbo Baggins’s cousin Otho, she covets Bilbo’s house, Bag End. She covets generally, in particular Bilbo’s silver spoons.

The Fellowship of the Ring, the first volume in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, was published in 1954. Vita Sackville-West was sixty-two. Renowned formerly as a novelist and award-winning poet, by the mid-1950s her reputation rested chiefly on the weekly gardening column she contributed to The Observer newspaper. It was one of the great success stories of British journalistic history, on one occasion generating a postbag of some 2,000 letters. Vita claimed to hate it.

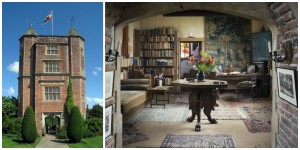

Nevertheless it was among factors that lay behind her award of the prestigious Royal Horticultural Society Veitch Memorial Medal in November 1954. Although Vita’s garden writing never specifically identified her own garden – at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent – it inevitably popularized those lavish acres which, more than any of her novels or poems, would ultimately form her principal legacy. At the time of Tolkien’s writing, Vita was among the most famous gardeners on the planet. Most adults reading The Fellowship of the Ring on first publication would have connected Lobelia – whose name, after all, is that of a flower – with the green-fingered aristocrat, Vita.

Vita had just enough in common with her fictional caricature to amuse Tolkien’s contemporaries. While Lobelia is haughty and high-handed, Vita bore the imprint of upper-class Englishwomen of her generation, in her exaggerated focus on background and family history. She may or may not have been actively snobbish – and different observers disagree now as in her lifetime. Certainly she considered not only that background mattered, but that it shaped a person’s outlook and character. ‘What is this thing, this strain,/ persistent, what this shape/ that cuts us from our birth,/ And seals without escape?’ she questioned in a poem called ‘Heredity’. More significant, however, and mirroring Lobelia’s attitude towards Bag End, which she regards as her husband’s family home through kinship with Bilbo, Vita was intensely attached to a single house. In Vita’s case that house was Knole, the Kentish seat of the Sackvilles for half a millennium.

Vita was brought up at Knole, formerly a palace of the archbishops of Canterbury, a house as big as a village with reputedly a room for every day of the year and some 52 staircases. As a small child, she probably imagined she would live there for the rest of her life. Only later did she realize that, as a girl, she was disqualified from inheriting both Knole and the family’s Sackville barony. It was the dilemma which has faced generations of aristocratic daughters, but for the young Vita its discovery proved a defining moment. It was a shock from which she never recovered. Much of her life was spent reclaiming Knole through a variety of surrogates, most notably the house she bought in 1930: Sissinghurst Castle, with its Tudor tower that so closely resembles Knole architecturally. Vita reclaimed Knole imaginatively too – in her writing.

The fiction Vita Sackville-West wrote as an adult plays and replays her personal story of dispossession in (loosely) disguised form. Over and over, her novels are about greed for land and houses. In The Heir, a Wolverhampton clerk inherits a Tudor manor house and refuses all sensible advice to sell it. In The Edwardians, Sebastian’s entire raison d’etre is his role as inheritor of Chevron, a fictionalised Knole. In The Dark Island, Shirin marries a man she doesn’t love, in order to live in his castle, which she does love, on his island which she loves even more. In The Easter Party, Walter Mortibois refuses to allow himself to love his wife Rose, partly so that he can conserve his energies for loving his Queen Anne house, Anstey. In a poem addressed to Knole, Vita claimed: ‘So I have loved thee, as a lonely child/Might love the kind and venerable sire/ With whom he lived./ God knows I gave you all my love./ Scarcely a stone of you I had not kissed.’

Knole formed the major emotional attachment of Vita’s life. Writing in Vogue in 1931, she described growing up there: ‘I could help to stir the jam in the still room or to turn the mangle in the laundry; I could beg a cake in the kitchen or a bottle of cider in the pantry; I could watch the gamekeeper skinning a deer or the painter mixing a pot of paint; my comings and goings remained unnoticed.’ More poetically she remembered childhood games played in the house’s glittering state rooms: ‘Small wonder that my games were played alone…/ I slept beside the canopied and shaded/ Beds of forgotten kings./ I wandered shoe-less in the galleries.’

In The Fellowship of the Ring we laugh at Lobelia’s awfulness, concur in other hobbits’ assessment of her as the nastiest of neighbours. Vita was not Lobelia Sackville-Baggins and the challenges of her life do not provoke laughter. Instead we celebrate the boldness and imaginative vigor of this uncompromising, romantic artist.

MATTHEW DENNISON is the author of the critically acclaimed The Last Princess and Livia, Empress of Rome and Behind the Mask: The Life of Vita Sackville-West. As a journalist, he contributes to The Times, The Daily Telegraph, Country Life, and The Spectator. He is married and lives in North Wales and Shropshire.