by Jack Kelly

Florence Kelley’s father, William, taught his daughter to read in 1866 using books that chronicled child labor. When she was seven, he had her studying “a terrible little book with woodcuts of children no older than myself, balancing with their arms heavy loads of wet clay on their heads, in brickyards.” And she didn’t just read. He took her to steel and glass factories where children younger than herself labored through fourteen-hour days and were routinely burned on the job.

It made sense that an FBI report issued in 1923 said that Florence Kelley had been “a radical all the sixty-four years of her life.”

Indeed, Florence Kelley is a woman who had an outsized impact on America’s labor standards, including on child exploitation. Her achievements in a wide range of reform movements, from minimum wage laws to racial justice to women’s suffrage, were rooted in the bare fact that, as she said, workers were being “plundered systematically of the fruits of their labor.”

Her father was a longtime Congressman from Pennsylvania and one of the founders of the Republican Party. He taught her that the duty of his generation was to “build up great industries in America so that more wealth could be produced.” Her generation’s responsibility was “to see that the product is distributed justly.” If you think this is a dusty notion of Gilded Age socialists, consider that between 1979 and 2020, the productivity of workers in the United States increased 62 percent while wages increased only 17 percent. Where did the difference go?

After graduating from Cornell, Florence traveled to Switzerland for further study. She married a Swiss medical student; they had three children and settled in New York. But her husband’s abuse prompted her to flee with her children to Chicago, where in 1891 she found a haven at Hull House. Social worker Jane Addams had established the settlement house two years earlier to aid immigrants.

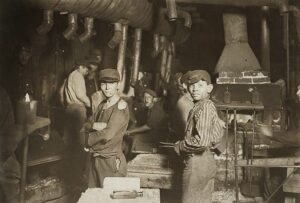

At the time, child labor was common. Eight-year-old oyster shuckers in Louisiana worked in canneries from three a.m. to five p.m. In Chicago sweatshops, kids went to work at three years old.

Kelley lived at Hull House for eight more years. She fought for laws that limited work hours for women and for prohibitions on child labor for kids under fourteen. She promoted an eight-hour day for all workers. She organized a detailed survey of sweatshops and small factories in the city’s slums. In 1893, the reformist governor of Illinois, John Altgeld, appointed her the state’s first chief factory inspector to make sure business owners complied with the laws. She supervised a staff of eleven inspectors.

Jane Addams called Kelley “the finest rough-and-tumble fighter for the good life for others, that Hull House ever knew.” During the Pullman Strike, the massive rail shutdown of 1894, she helped raise bail for union leader Eugene Debs and organized protests on behalf of the strikers. At the same time, she was gaining her law degree from Northwestern University.

In 1899, Kelley returned to New York. She became the director of the National Consumer’s League to put pressure on companies that mistreated workers. She worked with President Teddy Roosevelt to formulate the Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act during the early years of the twentieth century.

Always distinguished by an iron will and boundless energy, Kelley could not be stopped. She said that “no one needs all the powers of the fullest citizenship more urgently than the wage-earning woman.” Without the clout of the ballot, women could not influence the laws that kept them in a subordinate position. She spent thirty years fighting for women’s suffrage before it was achieved in 1920.

Kelley’s parents had both been avid abolitionists in the fight against slavery. Florence saw discrimination as a fundamental flaw in American society. With her friend W.E.B. DuBois she helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1917, she marched in a silent parade in New York City to protest the violence by white mobs that killed as many as 150 African American citizens of East St. Louis, Illinois.

If that wasn’t enough, she worked on city planning with the goal of reducing slums. And heeding her pacifist beliefs, she protested American intervention in World War I.

Florence died in 1932. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote that Kelley had “the largest single share in shaping the social history of the United States during the first thirty years of this century.”

Originally published on Jack Kelly’s Talking America.

JACK KELLY is a journalist, novelist, and historian, whose books include Band of Giants, which received the DAR’s History Award Medal. He has contributed to national periodicals including The Wall Street Journal and is a New York Foundation for the Arts fellow. He has appeared on The History Channel and interviewed on National Public Radio. He grew up in a town in the canal corridor adjacent to Palmyra, Joseph Smith’s home. He lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.