By Gerald M. Carbone

General John Sullivan took command of Lee’s Troops outside Morristown, and within a week he had them marching into Washington’s camp on the west side of the Delaware. Washington had first asked Lee to bring those men on November 17, when they were 6,000 strong; now, on December 20, enlistments for 1776 had expired, and their number had dwindled to about 2,000.

On New Year’s Eve, almost everyone’s term of service would expire, and Washington would be left with an army of about 1,200. “Ten more days will put an end to the existence of our Army,” Washington wrote to Hancock. The courier delivering this letter now had to ride more than 100 miles beyond Philadelphia, as Congress had quit that city in the face of imminent British invasion and moved its business to Baltimore. Because of this, Washington had asked for, and had been granted, greater powers to act without first consulting Congress on such things as appointments of minor officers, arresting people who refused to accept Continental currency, and impressing goods from civilians.

Washington had just about finished drafting his letter to Hancock when he received a brief, melancholy note that had been on the road 13 days from Rhode Island: A large fleet of British ships had sailed into Newport and without opposition dropped 6,000 troops. The Howe brothers now held Newport, a capital city at the head of Long Island Sound; New York; most of New Jersey; and were poised to strike Philadelphia at will. Washington feared that when the river froze, British and Hessian soldiers would emerge from their winter outposts in Trenton, Princeton, and Bordentown, stream across the river, and seize Philadelphia.

Washington wrote to Rhode Island’s governor: “It would give me infinite pleasure, if the situation of our Affairs in this Quarter, would allow me to afford you the assistance I could wish, but it will not. . . . How things turn out, the event must determine, at present the prospect is gloomy.”

Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia doctor and signer of the Declaration of Independence, visited Washington at his headquarters on December 23, 1776, and found him depressed. Washington sat at a writing desk, quill in hand, scratching the same phrase onto scraps of paper, a scarce commodity in camp. Rush wrote of this meeting: “While I was talking to him, I observed him to play with his pen and ink upon several small pieces of paper. One of them by accident fell upon the floor near my feet. I was struck with the inscription upon it. It was ‘Victory or Death.’”

For Washington, this was not an empty phrase. Before his troops disbanded, he would win a victory over the Hessian forces posted on the eastern bank of the Delaware, or he would die; there was no room for middle ground. The campaign of 1776—which had begun so promisingly with the evacuation of Boston—had become a disaster. On Long Island, he had been outflanked and lost 1,000 men; on Mount Washington, he had lost 2,000; on the retreat from Manhattan and during various skirmishes, he had lost another 1,000; he had also lost the ground—Long Island, Manhattan, and practically the entire state of New Jersey. Only the Delaware River had saved Philadelphia. On Long Island, Washington had nearly lost his army, and near Kip’s Bay, he had nearly lost his life; but worse than having his life threatened was the threat to his reputation. He had to do something, something bold and decisive, to get that back. And George Washington decided that he would capture the Hessian soldiers posted in Trenton.

“Christmas day at night, one hour before day is the time fixed upon for our attempt on Trenton,” Washington wrote to Colonel Joseph Reed on December 23. “For heaven’s sake keep this to yourself, as the discovery of it may prove fatal to us, our numbers, I am sorry to say, being less than I had any conception of—but necessity, dire necessity will—nay must justify any Attempt.”

On Christmas Eve, 1776, a procession of officers crunched across the crusty snow outside the Merrick House, the chilly, unfinished fieldstone house where Nathanael Greene was quartered. They came not for a war council to decide what to do but to hear what George Washington had already decided that they would do. The officers assembled there included Greene, two future presidents (Washington and James Monroe), a secretary of the treasury (Alexander Hamilton), and a secretary of war (Henry Knox). Greene and a few others were already privy to the plans that Washington then laid out: On Christmas Day, the troops would cross the Delaware, march under cover of darkness to Trenton, and attack the garrison of 1,400 Hessian soldiers. Once they took Trenton, they would move on and take Princeton, where Major General James Grant, now in command of all British and Hessian troops in New Jersey, had a strong garrison. (This was the same James Grant whose troops Washington rescued from annihilation at Fort Duquesne in the French and Indian War.)

Tactically, the attack plan that Washington laid out was too complicated to have much chance of success. He would split his army into three divisions, which would all make separate river crossings, at night, then somehow simultaneously converge at and below Trenton. It was the plan of an overly ambitious amateur.

* * *

Christmas Day 1776 dawned blue and cold. The temperature peaked at 30 degrees, and around noon, the main part of the army, about 2,400 men, gathered in camp to begin the march to McKonkey’s Landing on the milewide Delaware River. These troops, with Washington at their head, would cross the Delaware about nine miles above Trenton, split into two detachments under Generals Sullivan and Greene, and descend on the town as a pair of pincers squeezing the outpost from above; another 700 troops would ferry over directly across from Trenton to hold the bridge at the south end of town, and a force of 1,900 would cross farther south of Trenton to cut off the Hessian garrison in Bordentown from marching north to reinforce Trenton.

In general orders that morning, Washington had been so optimistic about his convoluted plans that he’d ordered his artillery detachment to carry drag ropes for hauling off all the Hessian cannons he was sure they would capture.

Washington’s troops marched to within a mile of the ferry landing, where they lined up by brigade, waiting for December’s early darkness. As they stood in the cold, Washington ordered officers to read aloud Thomas Paine’s latest pamphlet, The Crisis:

These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives everything its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price on its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated.

One by one, each brigade marched off toward McKonkey’s Ferry, so that by 3 P.M., the entire army was in motion. They crunched across week-old snow that had thawed and refrozen to a sharp glaze. A major, John Wilkinson, saw spots of red in the snow, “tinged here and there,” he wrote, “with blood from the feet of the men who wore broken shoes.”

By 4:30, the sky was dark enough to conceal the river crossing, and the embarkations began. Once again, Washington relied on his big artillery colonel, Henry Knox, to oversee the business of moving heavy stores: 18 field cannon, 350 tons of ammunition, draft horses, and 2,400 men. The wind blew from northeast, funneling down the Delaware Valley, driving before it large ice floes that had broken from the river’s edge. Through the roar of the wind in the gathering dark, Knox’s voice rang out, barking orders, loading the artillery and horses, embarking the brigades in correct formation.

Greene’s brigades loaded first, stepping gingerly into the boats—big, black boats, 40 to 60 feet long, used in peacetime for hauling iron and pig ore from the Durham Iron Works. At 6 P.M., Washington sent a dispatch downriver to Colonel John Cadwalader, commander of the 1,900 troops supposed to cross the river below Trenton: “I am determined, as the night is favourable, to cross the River.”

Colonel John Glover’s regiment of Marblehead fishermen poled and steered the freighted boats across the current, battling their way through big floes of ice that clunked heavily against their sides.

Washington, wrapped in a cloak, went over around 7 P.M. to view the landing parties. Ashore in New Jersey, Washington sat on a box that had contained a beehive and watched for hours while his plans slowly went awry.

Around 11 P.M., a heavy snow began. Wind whipped the snow and sleet into the faces of Glover’s men as they fought off the ice floes, their poles and gunnels glazed in ice. The artillery was supposed to cross first, but the last cannon did not roll up the New Jersey riverbank till 3 A.M.

By the time everyone was across and ready to march the nine miles to Trenton, it was four in the morning, too late to spring a surprise, predawn attack on the Hessians. Washington considered withdrawing but concluded that retreat would be too dangerous; if his troops were discovered midriver, they would be sitting ducks for marksmen on the banks. There was no turning back; they’d have to fight by daylight.

The troops stepped off—thankfully putting the windblown sleet at their backs. After two hours marching in the storm they reached the dark village of Birmingham, where Washington gathered his generals and told them to set their watch by his. He then split his division in two: Greene and Washington led 1,000 men along Scotch Road while Sullivan marched his 1,400 troops down the River Road. The roads were equidistant, four miles, to Trenton.

Washington ordered all lanterns doused, and as they marched the troops kept silence. En route, Sullivan sent a horseman to tell Washington that his men were complaining that their gunpowder was wet. Washington sent a messenger back with an answer: Use the bayonet. “I am resolved to take Trenton.”

Peering through the sleet and snow, Washington spied the Hessian advanced post—a cooper’s shop on Pennington Road—at exactly 8 A.M. Lieutenant Andreas Wiederhold of the Knyphausen Regiment happened to step out of the guardhouse at that moment and saw Washington’s troops heading his way. He thought he was looking at a small party of skirmishers, and called his 20 men to arms.

At 8:03, Washington heard firing to his right, and he knew that Sullivan’s troops had matched his column step for step and was now attacking the outpost on River Road. Washington’s troops fired from 300 yards; they came on, firing two more volleys, before Wiederhold signaled his men to shoot. The Hessian guard fought, briefly, before realizing that they were vastly outnumbered. He pulled back into the main streets of Trenton, where the main body of troops, barracked between King and Queen streets, was just beginning to stir.

“We presently saw their main Body formed,” Washington reported to Congress, “but from their Motions, they seemed undetermined how to act.”

The first of the Hessians to spill out tried filing off to their left but soon ran into Sullivan’s troops, who drove them back into the town. Knox’s artillerymen unlimbered cannon at the top of the two main streets and touched them off. With an explosive roar, cannon cut down the enemy troops with grapeshot as they poured from their barracks. Acrid gun smoke hung in the air, thickening with each blast of cannon and musket, mingling with the snow so that Washington could not see Sullivan’s troops sweeping into town to his right.

Washington ordered a regiment of Greene’s troops to form a battle line to his left and advance through the fields and apple orchard east of town. With Sullivan’s troops sweeping in from the west, Greene’s troops sealing off the Princeton Road to the east, and Knox’s artillery thundering from the north, the Hessians found themselves in a gauntlet of fire. Grapeshot and musket ball sliced through the fog of gun smoke and snow, buzzing past their heads, in some cases, striking bodies with a sickening crack.Colonel Johann Rall, the Hessian officer who had taken the sword of surrender at Fort Washington, dropped from his horse with fatal wounds from two musket balls in his side. About 500 Hessians managed to dash across a bridge across Assunpink Creek at the south end of town before Glover’s regiment sealed it off.

“Finding from our disposition, that they were surrounded, and that they must inevitably be cut to pieces if they made any further Resistance, they agreed to lay down their Arms,” Washington wrote Congress. Major Wilkinson carried news of the Hessian surrender to Washington, who was just then riding down a snow-slickened King Street, its snow tinged red with blood. Washington firmly grasped Wilkinson’s right hand.

“Major Wilkinson,” he said, “this is a glorious day for our country.”

Washington huddled with his officers for a brief war council to decide: Should they still press on for Princeton to attack the British garrison there? His two youngest generals, Greene and Knox, said they should. The rest said that they should not: The two divisions that were supposed to cross to the south of them had not been able to make the crossing, leaving them exposed to reinforcements from the large Hessian outpost at Bordentown. The victory had been so complete and so necessary to boost morale that they should not jeopardize it. Besides, their troops were cold, wet, and exhausted. Even as they talked, troops were breaking into hogsheads of rum and numbing themselves with drink. At noon they marched out of Trenton, slogging along slushy roads the eight or nine miles to the river crossing, leaving behind 22 dead Hessians and many of the 84 wounded. With them were 918 prisoners and six brass cannon, hauled along by the drag ropes that Washington had insisted on bringing. The Americans had none killed and two slightly wounded, including future president James Monroe.

Again they stepped into the Durham boats to cross the Delaware at night with a cold wind driving ice floes down the valley; this time, three men who boarded the boats never made it alive to the other side. In crossing the Delaware, they froze to death.

After two river crossings, a battle, and two sleepless nights, George Washington finally slept at his new headquarters, an old yellow house about five miles west of McKonkey’s Ferry on the Delaware.

Moving thousands of troops across a freezing river in a deadly storm to attack Trenton had been an act of desperation—but it had worked. Alarmed by what had happened at Trenton, Hessian soldiers fled from their posts in Bordentown, Mount Holly, and Black Horse; Washington saw this as an opportunity to take advantage of the Hessians’ panic by following up with another attack.

At 10 P.M. on December 29, after just two days of rest, Washington’s men again stood on the cold clay banks of the Delaware awaiting boats to shuttle them across the river. That night it wore a skim of ice too thin to support the weight of men but thick enough to impede the progress of boats. This crossing took two days. Washington’s troops weren’t fully assembled in Trenton until December 31, 1776—for many, their enlistments would expire the next day.

After the hard river crossing, in which half of his troops had camped a night in six inches of snow without blankets or tents, Washington rode to inspect a New England regiment of his veteran troops encamped in Trenton. These men had been with him throughout 1776—they had rejoiced at the evacuation of Boston, been driven from Long Island and White Plains, slogged for 80 miles across New Jersey; they looked less like soldiers than like ragged refugees. Washington told them that they had done a good job and he was thankful. If they would extend the terms of their enlistment for just six weeks, he would top their regular pay with a bounty of $10.00. His regimental officers called for volunteers to step forward and a drummer beat a roll.

Not one man moved.

Frustrated, Washington wheeled his horse around in a circle and rode along his men. A sergeant who was present wrote a recollection nearly 50 years later in which he put words into Washington’s mouth that likely weren’t verbatim, but probably caught the spirit of Washington’s words:

My brave fellows, you have done all I asked you to do, and more than could be reasonably expected. But your country is at stake, your wives, your houses, all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves put with fatigues and hardships, but we know not how to spare you. If you will consent to stay but one month longer, you will render that service to the cause of liberty, and to your country, which you probably can never do under any other circumstances. The present is emphatically the crisis that will decide our destiny.

Again the drum rolled. This time there were murmurs (“I will remain if you do”), and gaunt veterans came forward till all but the lame and the nearly naked stood in a line. In all, about 2,400 regular soldiers agreed to stay on for six more weeks to help Washington rid the Jerseys of the British. Afterward, Nathanael Greene wrote: “Let it be remembered to their Eternal honor.

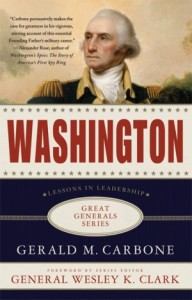

Excerpted from Washington: Lessons in Leadership by Gerald M. Carbone.

Copyright © Gerald M. Carbone, 2010.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

GERALD M. CARBONE is the author of Nathanael Greene: A Biography of the American Revolution.He was a journalist for twenty-five years, mostly for the Providence Journal andhas been recognized as an expert on the life of Nathanael Greene by various historical societies. He has won two of American journalism’s most prestigious prizes–the American Society of Newspaper Editors Distinguished Writing Award and a John S. Knight Fellowship at Stanford University.