by A.E. Hotchner

In the spring of 1948, I was dispatched to Havana on the ridiculous mission of asking Ernest Hemingway to write an article on “The Future of Literature.” I was with Cosmopolitan, then a literary magazine, before its defoliation by Helen Gurley Brown, and the editor was planning an issue on the future of everything: Frank Lloyd Wright on architecture, Henry Ford II on automobiles, Picasso on art, and, as I said, Hemingway on literature.

Of course, no writer knows the future of literature beyond what he’ll write the next morning. Checking into the Hotel Nacional, I took the coward’s way out and wrote Hemingway a note, asking him to please send me a brief refusal. Instead of a note, I received a phone call the next morning from Hemingway, who proposed five o’clock drinks at his favorite Havana bar, the Floridita. He arrived precisely on time, an overpowering presence, not in height, for he was only an inch or so over six feet, but in impact. Everyone in the place responded to his entrance.

The two frozen daiquiris the barman placed in front of us were in conical glasses big enough to hold long-stemmed roses.

La Feria de San Fermín, Pamplona, Spain

We left for Pamplona the following day and, as arranged, met up with Mary and several of their friends in Pamplona, which is just over the French border in northern Spain. La Feria de San Fermín was seven days and seven nights melted into one, just as Ernest had described it, a raucous drinking, dancing, feasting celebration of the bulls, which ran through the streets every morning and died in the ring every after noon.

Participating in a complete run of the feria certainly heightened my admiration for the way it is depicted in The Sun Also Rises, including the after noon picnics we enjoyed on the banks of the Irati River, so prominent in the book. Hemingway captured not only the events but, more important, the emotional nuances that gave the book its thrust.

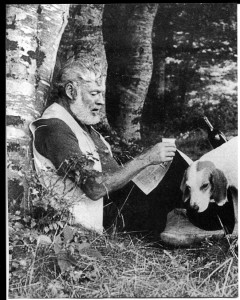

On one picnic after noon, high up in the moss-carpeted, beech- wooded forest above the Irati, Ernest was enjoying a brief reprieve from the Pamplona tumult, when a gentle hound dog mysteriously came out of the forest and went over to where Ernest was sitting with his back against a birch tree. I had my camera suspended around my neck and I snapped their picture. Of all the many pictures I took of Hemingway over the years, that one was my favorite. The dog settled down next to Ernest and they both closed their eyes and took a little nap together.

One after noon, while Ernest and I were sitting in choice barrera seats in the bullring, waiting for the after noon’s corrida to start, Ernest said that he used to sit in these seats with Lady Duff the first time they came to the feria.

Image is taken from the book Hemingway in Love by A. E. Hotchner

“She was a rare one, the Duff was. Specially liked the part where the bull tore up the underbelly of the horse and its guts trailed around under it as the picador went about his business. Of course, horses have protective mattresses now, but not the banderilleros, who, after they stick the barbs, try to vault over the barrera before the bull can nail ’em. She loved that chase, always rooting for the bull, and loved it when the bull occasionally hooked the matador in the ass on his way over the fence.

“There was a night here when Duff and I might have gotten it on. There was something about the way she dressed and talked and her utter disregard for convention that was exciting. And yet, that was why it didn’t work. At the last moment, she begged off. ‘I don’t have much in the way of scruples or beliefs or religion,’ she said, ‘but what I have in place of God is my rock- solid resolution not to fuck married men.’”

Ernest was correct about sleep and the lack of it. Sometimes when it got very late and I was in dire need of closing my eyes, I curled up in the back of the Lancia, which was parked near the central town square. Occasionally Ernest would join me in the front seat.

One night we were invited to a private club where there was a lively band, with everybody singing and drinking the good local wine as they danced. In the small hours of the morning we managed to make our unsteady way to the Lancia. Ensconced in the front seat, Ernest sipped from an uncorked bottle of Navarre red he had carried from the club.

“Damn sight better’n the last one,” he said.

“Last one?” I said from the backseat, not reading him.

“Yep. Back in ’26 it was a glum feria with the Murphys and Hadley. We didn’t dance in the street.”

“Why glum?”

“I thought Hadley and I had been getting along all right, she putting up with my seeing Pauline, but I found out I was deluding myself. I guess it was the frivolity of Pamplona where everyone was having a good time, that got to her. It was during the next to last bullfight of the feria that Hadley said, ‘You know something, Ernest, your veronicas have been wearing me down and I want to get out of the ring before it’s too late.’

“I pretended not to know what she was talking about, but I knew.

“‘I really can’t be someone I’m not.’

“Meaning?

“‘When we get back I’m going to find a separate place for Bumby and me.’

“I wasn’t prepared for this. I loved her, and now she was defending her dignity and I couldn’t be the one taking it away from her.

“‘You know sometimes the matador gets gored,’ I said lamely, ‘and if you leave …’

“‘I won’t go back to the apartment with things as they are. I’m going to leave you at the Gare de Lyon.’

“But we’ll be seeing each other….’

“‘No, no good nights after dinner…. Once apart … well … apart.’

“There were tears down her cheeks in the after noon sunlight. I felt like an intruder had risen up and struck me down.”

“Papa, at that moment did it occur to you,” I said, “to promise to give up Pauline in order to get Hadley to stay?”

“No, I wasn’t ready for this confrontation, and with the commotion of the bullring around me, the olés of the spectators, the blaring music of the band, the performance of the matador on the sand, my head wasn’t working. I just accepted what she said as a kind of punishment, especially when she said, ‘You well know, Ernest, that when a corrida goes past the time limit, it is called off and the matador and the bull go their separate ways.’”

Hemingway drained off the last of his wine. “I told you about going back to Paris in the train compartment the next day, didn’t I?”

I said he had.

He put the empty bottle on the floor, and his head resting against the seat back, he fell asleep.

A.E. HOTCHNER is a life-long writer and the author of seventeen books, including Hemingway in Love, O.J. in the Morning, G & T at Night and Papa Hemingway, a critically acclaimed 1966 memoir of his thirteen-year friendship with Ernest Hemingway. Hotchner’s memoir, King of the Hill, was adapted into a film by Steven Soderbergh. In addition to his writing career, Hotchner is co-founder, along with Paul Newman, of Newman’s Own foods. He lives in Connecticut with his wife and his indispensable parrot, Ernie.