by Joe Starita

On March 14, 1889, Susan La Flesche Picotte received her medical degree—becoming the first Native American doctor in U.S. history. She earned her degree thirty-one years before women could vote and thirty-five years before Indians could become citizens in their own country.

By age twenty-six, this fragile but indomitable Native woman became the doctor to her tribe. Overnight, she acquired 1,244 patients scattered across 1,350 square miles of rolling countryside with few roads. Her patients often were desperately poor and desperately sick—tuberculosis, small pox, measles, influenza—families scattered miles apart, whose last hope was a young woman who spoke their language and knew their customs.

A Warrior of the People is the story of an Indian woman who effectively became the chief of an entrenched patriarchal tribe, the story of a woman who crashed through thick walls of ethnic, racial and gender prejudice, then spent the rest of her life using a unique bicultural identity to improve the lot of her people—physically, emotionally, politically, and spiritually. Keep reading for an excerpt of this moving biography.

* * * * *

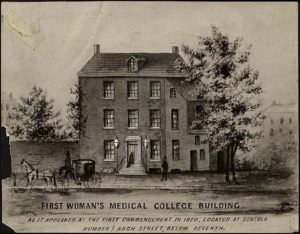

Susan liked people. And she had a genuine hunger for new experiences, to see and do a variety of things, to meet men and women much different from her, men and women who often were just as interested to know more about her, who enjoyed showing off their city to the charming, inquisitive Indian girl from the Great Plains. So during her three years at the Woman’s Medical College, Susan’s social and artistic life blossomed.

It began almost immediately. A few days before Christmas 1886, the well-to-do, well-connected Mrs. Miesse took the youngest daughter of an Omaha Indian chief to see Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera The Mikado, which Susan loved and couldn’t wait to tell her sister Rosalie about. And then Mrs. Miesse’s friend, a theater manager, gave her three tickets to A Wife’s Peril, starring the “Jersey Lily” herself, Lily Langtry, one of the era’s most glamorous stage actresses—and of course she gave one to Susan, and soon they were transfixed watching. “I can say now I have seen a beautiful woman,” Susan flatly declared afterward. Then one week it was off to see Hannah Whitall Smith, among the celebrated temperance speakers of the day, and another week Miss Haynes sent her a ticket to hear the Germania Orchestra, said to be the city’s finest. And then came an invitation to journey out to Girard College to watch more than one thousand boys drill in parade formation, and Susan couldn’t quite fathom the splendor of so many buildings inspired by Grecian architecture, including one modeled after the Parthenon. Then it was off to see another play, The Little Tycoon, and then an invitation to attend a standing-room-only Sunday service in the city’s grand Catholic cathedral, with its gorgeous paintings, altars, flowers, and music—which on this day included selections from Handel’s Messiah. Then around Thanksgiving, Mrs. Clarkman escorted Susan to the Academy of Fine Arts, where the marble staircase, the huge orchestra, and all the violins and flutes and horns and her personal favorite, the mandolin, overwhelmed her. And then they walked to the academy’s galleries of paintings and sculptures, and she couldn’t quite comprehend the magnificence of all the Benjamin West paintings, including The Death of General Wolfe and Christ Rejected, which was Jane Austen’s favorite. They had entered the academy at four p.m. and thought they had been inside no more than ninety minutes. They were surprised to discover it was six forty-five p.m. when they finally left.

With each passing month, when Susan wasn’t exploring the city’s vast fine arts world or immersed in coursework, she was often with her classmates, young women her own age who were quickly becoming her friends. After about five months, she finally mastered Philadelphia’s complex streetcar system, and after her first-year exams were over, she and “some of the girls” set off on an extended tourist excursion through the City of Brotherly Love. Before it ended, they had visited Old Swedes’ Church, the Delaware River, Philadelphia City Hall, Ben Franklin’s grave, and Independence Hall.

But no matter how much art, architecture, music, and society she absorbed, Susan never lost sight of who she was or where she came from. And she always looked to maintain a bridge to her people and traditions wherever and whenever she could. The nearby Lincoln Institute, a post–Civil War orphanage, was filled with Indian children, so Susan often went to see them. The Educational Home in West Philadelphia, which she and her friends visited many times, housed a number of Indian boys who “all looked very well & happy,” she was delighted to tell her family. One February day, about 130 Carlisle Indian boys and girls teamed up with some Hampton Indian students for a concert, and Susan made sure she was there to see and hear them. She was proud that so many of those students were from her tribe, and she made it a point to tell Rosalie that “the Omahas have high standing at both schools.”

If Susan sought cultural sustenance and inspiration in the hallways of the local Indian orphanages and boys’ homes, her attentions were reciprocated. Not long into her medical studies, her name began to crop up in Indian school publications and conversations, a name increasingly held up as a motivational tool, a role model for others to aspire to. Soon after the joint band concert, Susan described the reaction she got from some of the younger Omaha students. “I think they must have been so glad to see me and I think my graduation honors at [Hampton] must have made them feel so proud of me,” she told Rosalie. The Carlisle school newspaper described her as one of Hampton’s most gifted students, and most of their students knew she had received the gold medal and finished second in her graduating class.

If Susan sought cultural sustenance and inspiration in the hallways of the local Indian orphanages and boys’ homes, her attentions were reciprocated. Not long into her medical studies, her name began to crop up in Indian school publications and conversations, a name increasingly held up as a motivational tool, a role model for others to aspire to. Soon after the joint band concert, Susan described the reaction she got from some of the younger Omaha students. “I think they must have been so glad to see me and I think my graduation honors at [Hampton] must have made them feel so proud of me,” she told Rosalie. The Carlisle school newspaper described her as one of Hampton’s most gifted students, and most of their students knew she had received the gold medal and finished second in her graduating class.

When the younger Indian musicians arrived in Philadelphia for the concert, Susan said, “The boys were kind of glad to see me there as the Omaha girl who was studying medicine.” A few years later, Talks and Thoughts, a newspaper edited and published by Hampton’s Indian students, ran a small reminiscence that began: “Sometimes when we are skipping around in Winona we remember one sweet-faced Hampton sister Susie, who used to help us so much with our games.” The paper noted how far Susie had come since her Hampton days, how she might one day even have her own hospital, and how high she had set the bar for all the other Indian students. “There is not much use trying to be as smart as she is,” the paper concluded, “but I guess it wouldn’t hurt us to try and be as good.”

And wherever she went, whether it was Hampton or the orphanages, to the home for boys or throughout Philadelphia, there was always the question of identity—about how people see themselves, how others see them, about who gets to decide, who gets to choose the cultural attributes that people select to create identities for themselves and for others—that kept cropping up again and again, in different places, at different times, in different ways.

JOE STARITA was the New York Bureau Chief for Knight-Ridder newspapers and a veteran investigative reporter for The Miami Herald. His stories have won more than two dozen awards, one of which was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for local reporting. For the last nine years, he has held an endowed chair at the University of Nebraska’s College of Journalism. The Dull Knifes of Pine Ridge won the MPIBA Award and received a second Pulitzer nomination. He is also the author of “I am a Man.”