by Jack Kelly

2019 marks the 150th anniversary of the completion of the first transcontinental railroad. When builders pounded the golden spike at Promontory Point, Utah, on May 10, 1869, they opened a new era in transportation. But long train trips required innovations in passenger cars. Sleeping cars operated by the Pullman Palace Car Company solved a problem and influenced American taste for decades to come.

To enable passengers to sleep comfortably, the railroads needed a car that could be easily converted from a coach to a dormitory. Most didn’t want to tie up capital in such elaborate cars or get involved in the complex chore of operating them. It made more sense to turn the business over to a contractor, a specialist.

Chicago businessman George M. Pullman did not invent the sleeping car — credit for that goes mostly to Theodore T. Woodruff, an upstate New York wagon maker whose car debuted in 1857. But Pullman added his share of innovations. More importantly, he systematized, then largely monopolized, the entire world of specialty railroad cars.

Although U.S. trains, unlike those in Europe, were not separated into first, second and third classes, many passengers wanted a tonier atmosphere than was available in a coach car and preferred to stretch out at night. Acutely sensitive to the trends of his time, Pullman saw that Americans of the coming Gilded Age would be attracted to luxury and willing to pay for it.

Comfort was important. Traveling over early, hastily constructed rail beds, trains inevitably swayed, rattled and clacked. Most passenger cars ran on two four-wheel trucks. Pullman used eight-wheel trucks supplied with an improved suspension for a smoother ride. He even added lighter wheels with pressed-paper cores to minimize jolts. He installed double-glazed windows and doors for quiet. The ventilators in a Pullman car brought in fresh air but filtered out dust and cinders.

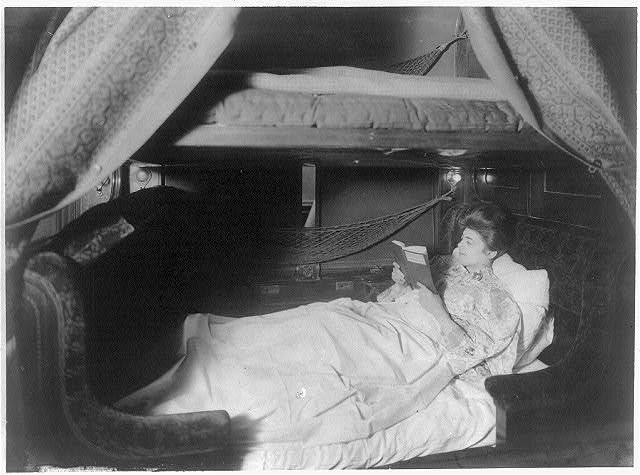

The real glory of the Pullman car was in the decor. Victorian taste ran toward the baroque, and Pullman offered the utmost in ornamentation: carved walnut paneling, polished brass fittings, beveled French mirrors, Brussels carpets, brocade, tassels and fringe. At night the berths were made up with pristine white sheets. George Pullman believed, he said, in the “commercial value of beauty.”

Although the $2 extra fee that a passenger paid to ride in a Pullman car was twice the daily wage of a laborer, the cars were not used exclusively by the wealthy. The growing middle class was attracted to the sense of privilege and status. They felt they were able, however briefly, to emulate the rich. “What was once really tedious,” one traveler said, “has become a pleasure.”

For all their refinements, Pullman’s cars were only one element of an entire system. He hired Pullman conductors and porters. His company maintained the cars’ interiors and did all the laundry. A company manual broke a task as simple as offering a passenger a glass of beer into fifteen steps. The uniformity and attention to detail of the Pullman experience reassured customers.

George Pullman was ahead of his time in his understanding of the value of publicity. Today, we call it building a brand. He created news by touting the elaborate features of his latest cars. He took reporters on champagne-drenched excursions to review the amenities. In 1870, he arranged for members of the Boston Board of Trade and their families to travel on the first chartered rail journey across the country. The all-Pullman train so impressed the passengers that they pressed New England railroads to adopt Pullman cars.

Dining cars were another Pullman innovation. Before George Pullman introduced his first diner, the Delmonico, trains stopped briefly at stations to allow passengers a hurried meal. Dining cars removed this inconvenience. Although they rarely made money for the railroads, the cars offered yet another draw for those willing to pay for luxury.

The Delmonico, named after a premier New York City restaurant, featured an eight-foot-square kitchen, two cooks and four waiters. As many as 48 customers could eat at one time, and the staff typically serving 250 meals a day. A passenger chose from among more than eighty dishes, including oysters on the half shell, turtle soup, entrees like stuffed loin of veal, venison and quail, a dozen vegetables and more than twenty desserts. Fine china and crystal were standard.

Another Pullman specialty was the parlor car. For an extra fee, a passenger could relax in an upholstered armchair, which swiveled to allow a view of the scenery. Wide windows and elegant furnishings added to the sense of privilege.

An important Pullman innovation was the vestibule train. Early cars had platforms front and back so that passengers had to step outside to move from one car to another. The vestibule was a spring-driven accordion covering that allowed cars to be joined seamlessly. It made moving from car to car much easier and helped to stabilize the train at high speeds.

The ultimate in Pullman extravagance was the private car, known in the business as a “private varnish.” These cars allowed the ultra-wealthy to travel in comfort without rubbing elbows with fellow passengers. A typical car might have an open fireplace and a marble bath. Italian artists supplied paintings of fuchsias and hummingbirds for the ceiling. Lamps and fitting were gold plated. The car itself contained several bedrooms, a central parlor/dining room, and kitchen.

Private cars, which sold for $50,000 and up ($1.3 million in today’s currency), brought both profits and publicity to the Pullman Company. Business magnates and opera stars outdid each other in the excessiveness of the appointments. Reporters swooned over the latest private varnish in newspapers. The Pullman brand flourished.

In fact, only a minority of private cars were owned by individuals. Most were the property of railroad companies. Executives used them when they moved around the country overseeing their lines. When the cars were not in use, they were rented to individuals intent on an excursion in style. George Pullman leased his own private car for $85 a day.

For all his success, George Pullman, at age 63, found himself embroiled in controversy. The year was 1894. The country was gripped by an economic depression such as it had never seen. Pullman cut his workers’ wages, but not the rents in his paternalistic company town. A strike blew up into a national crisis as railroad workers stopped handling Pullman cars. Pullman refused to allow the dispute to go to arbitration, prolonging the ordeal. The U.S. Army intervened; men and women died. Pullman was pilloried for his intransigence, even by some of his friends.

The resentful sleeping car king died three years later. But the Pullman company remained enormously successful for the next fifty years. And although tastes swung far away from the Victorian excesses that had been the Pullman trademark, the demand for luxury never abated. Pullman cars remained the standard of quality and elegance through half the twentieth century.

Jack Kelly is a historian and novelist. His latest book, The Edge of Anarchy: The Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest Labor Uprising in America, details Eugene Debs’s leadership of the Pullman Strike.