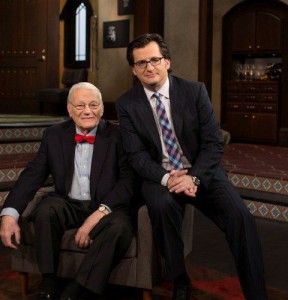

by Ben Mankiewicz

Writing about my father should be easy. But it isn’t. Writing is supposed to be a breeze if your last name is Mankiewicz. We have a long history of being clever. My grandfather Herman Mankiewicz wrote Citizen Kane, for crying out loud. My great-uncle Joe Mankiewicz wrote All About Eve. My uncle Don is Oscar- nominated for the screenplay I Want to Live! His son, my cousin John, is a successful writer on television, currently working on House of Cards for Netflix. Another cousin, Tom, practically invented the term “script doctor,” co- writing Superman and Superman II, as well as writing three James Bond movies. My brother, Josh, is regarded as one of the best writers and interviewers in television journalism; he’s been a correspondent for Dateline NBC for nineteen years.

And then there’s my father. If my dad had stayed in Hollywood, I have little doubt he’d be considered one of the great screenwriters of his generation. But instead, he moved back east and entered politics, where he wrote speeches and helped craft the messages of Robert Kennedy and George McGovern, two men I idolize.

I think the difficulty in writing about Dad comes from reconciling the two Frank Mankiewiczes. First, there’s the public one, the one with the epic quality to him. That’s the man who fought in World War II, proudly urinating for his country during the Battle of the Bulge, peeing on the frigid tires of his jeep to melt the ice. I fear I can’t do that man justice; after all, how many fathers have led the Peace Corps in Latin America and killed Nazis in Europe? It’s a short list.

Image is in the public domain via atlantamagazine.com

Then there’s the dad I lived with at home, the father who went to 95 percent of my high school basketball games, taught me to follow politics, read the paper every day, and start a serious love affair with baseball, and saddled me with a moderately compulsive passion for sports gambling. That guy wasn’t epic. But he was present—which is better.

Often, as you might imagine, those two persons collided. Let me tell you a story that took place often, on nearly any Saturday in the mid- to late 1970s, when I was between seven and thirteen years old. Dad and I did the grocery shopping on most Saturdays. We lived in Washington, D.C., but went to a market out on Connecticut Avenue in Chevy Chase, Mary land. It was big. And freezing. We actually called it “the cold market.” I loved spending time with my dad, but I didn’t like those Saturday mornings. I was a skinny kid, sensitive about my slender arms (I had a short- lived junior high nickname: Wire- Arms Willie. No clue where the “Willie” came from). I felt cold and weak in that market, while Dad always seemed fiercely strong. He loved the cold. The air- conditioning in our house was permanently set to arctic.

Read more about the Mankiewicz family here

While I’d be enduring my unmanly shivering, week after week, Dad would be approached by a total stranger who’d stop us in the market and say something along the lines of “Mr. Mankiewicz, you don’t know me, but I just wanted to thank you.” Then this person would indicate he’d worked for Dad either in the Peace Corps, or in the Kennedy campaign, or for George McGovern, or later at NPR.

Once back home, my “big shot” dad would inevitably and inadvertently remind me that he was a regular guy. His level of frustration at not having a pen next to the phone to take notes was legendary in our house. “Why aren’t there any goddamn pens next to the phone?” he’d bellow before glancing down and seeing a pen or two obscured by the newspaper or book he’d left there. “Oh, never mind.” In the recorded history of time, nobody ever lost and regained his temper more quickly than Frank Mankiewicz.

Dad also tried his hand—with memorable awkwardness—at post-sexual- revolution parenting. When I was no more than thirteen, driving in our neighborhood, Dad downshifted as we headed down the hill away from our house. “You’ll enjoy driving,” he said. “But remember, the car is not an extension of your penis.”

I want to have a son just to impart that random piece of advice.

I was an incredibly shy kid, not speaking in class until eighth grade, so I was easily intimidated by a father leading such a public life. Eventually, though, I came out of my shell late in high school, growing comfortable that I could fall short of my father’s greatness yet still lead a happy and successful life. But then, after my junior year at college, I took a trip to Los Angeles. At a party, I was introduced to the host, who heard my name, looked me over, gave me a little courtesy bow, and said, “Welcome, Hollywood royalty.”

Growing up in D.C., I of course knew of the Mankiewicz family’s Hollywood accomplishments, but I was my father’s son first and foremost. To me, politics was the family business, not movies. But suddenly, three thousand miles from home, I was reminded of an additional weight: Not only was I Frank’s son, but I was also Herman’s grandson; Joe’s great- nephew.

Don’t get me wrong. I wouldn’t trade the legacy of my last name for anything, but being a Mankiewicz carries a heavy expectation, subtle but undeniable. And ultimately, inescapable. The night I started writing this, the television show Jeopardy! featured the category “Mankiewicz in the Movies.” I even gave one of the clues (we’d shot it months earlier at Turner Classic Movies). Seeing our name on- screen in that context was a surprising thrill. Winning an Oscar for writing Citizen Kane is nice, but having an entire Jeopardy! category to ourselves? That’s exhilarating. Herman Mankiewicz— great as he was— was never trending on Twitter.

But typically, attached to the excitement came the burden of expectation. As the cousins of my generation texted back and forth about Jeopardy!, Nick Davis, the son of my dad’s sister, Johanna Mankiewicz Davis, wrote to all of us in Jeopardy! speak: “What is pressure?”

I’ve learned— and happily accepted, I think— that pressure is part of the deal of being a Mankiewicz. If you’re vaguely in the public eye—as many of us are— the presumption is you’d better be the smartest, funniest, wittiest guy at the dining room table, in the conference room, on the e- mail chain.

And certainly I feel that pressure, but I know I’ll never be the smartest, the funniest, or the wittiest. That job belongs to my dad.

FRANK MANKIEWICZ (1924-2014) was a public relations consultant, lawyer, writer and journalist. He is best known as Robert F. Kennedy’s press secretary but also as the president of NPR, regional director of the Peace Corps, and George McGovern’s campaign director

DR. JOEL L. SWERDLOW is an author, editor, journalist, researcher, and educator. A senior writer and editor at National Geographic for 10 years, his published works include To Heal a Nation: The Story of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial