by Mariah Fredericks

Author Mariah Fredericks sets the scene for her latest novel, Death of an American Beauty, as she traces the rise of ragtime in New York City in the early 1900s.

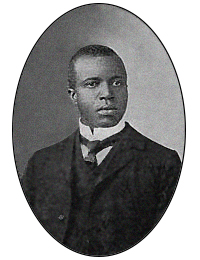

This photo is in the public domain via Wikicommons [PD-US Expired]

Ragtime—it’s quintessential old-timey American sound. Wildly popular from 1895 to 1919, the “ragged” or syncopated music immediately evokes a simpler, sweeter time of parasols, lemonade, and straw hats. It’s the subject of EL Doctorow’s epic of early 20th century New York, the soundtrack for The Sting—and seemingly an entire era of pre-WWI American innocence. It’s difficult to imagine anyone being shocked by “Maple Leaf Rag” or “Frog Legs Rag.”

And yet shocked people were. In 1912, a letter writer to the Times bemoaned ragtime’s immoral influence, especially on the young and urged those in power to “stamp out the epidemic of these positively dangerous songs.” Not only were the rhythms provocative, but the songs often featured “marital infidelity, risqué situations, and crude twistings of coarse phrases.” It wasn’t just John Q. Public who was horrified. The American Federation of Musicians adopted a resolution denouncing ragtime songs as “unmusical rot” and pledged to suppress the playing of “such musical trash.”

This photo is in the public domain via Wikicommons [PD-US Expired].

Of course, as with most American music innovation, the true scandal lay in the fact that ragtime started as an African American form. Scott Joplin was the “King of Ragtime,” composing more than one hundred pieces, including “The Entertainer.” Despite the enormous popularity of his music, Joplin died impoverished at the Manhattan Psychiatric Center in 1917 and was buried in an unmarked grave in Queens.

Ragtime, and its impact, is one of the threads in my third Jane Prescott mystery, Death of an American Beauty. In this novel, lady’s maid Jane Prescott has a week off. She’s a young woman; I wanted her to have some fun. And one of the ways a young lady of 1913 might have fun would be dancing. Inspired by Vernon and Irene Castle, she would have danced the Grizzly Bear and Turkey Trot to ragtime in the dance halls that were springing up all over New York, turning the metropolis into the “City of Dreadful Dance.”

So how to hear ragtime as it was experienced in its day—not as your great grandmother’s music, but something new, subversive, sexy. Certainly the song titles of the era are more suggestive than you might expect. Irving Berlin may be best known for God Bless America, but his earlier songs are obsessed with sex, with titles that capitalize on the erotic vagaries of the word “it.” “After You Get What You Want, You Don’t Want It,” “Do it Again,” and “Everybody’s Doin’ It Now.” Having performed as a singing waiter in some of New York’s seedier clubs as a young man, Berlin had expert training in popular tastes and knew that while Gilded Age New York might want its young people to exist in the Age of Innocence, young people had different ideas.

As my old chorus teacher will tell you, I understand nothing about music. But Jane wouldn’t have heard ragtime as a music scholar. So I listened to the music people danced to before ragtime and the turkey trot: the waltz. The waltz was also considered scandalously erotic; when you compare it to the formal distances dictated by the reel and the mazurka, the heady sensation of being whirled around a dance floor with your partner’s arm around your waist, might well have seemed a blatant invitation to still more intimate and heedless embraces.

But when one thinks of a waltz, one imagines a ballroom, an orchestra, men in evening dress, ladies in ballgowns—gloves on everyone’s hands—and a crowd of well-heeled chaperones supervising the young people’s every move.

Whereas ragtime and the dance halls where it was heard are unquestionably, impudently popular. Even now, you can hear that it’s music for the masses. It’s brashly American rather than elegantly European. You don’t need anything but a piano and space. One of the first things that strikes the ear is the speed; it sounds naughty, as if you’re moving fast enough to get away with something. It’s young people’s music, full of sass and bounce, evoking a generation ready to speed into the future, leaving their elders behind. Listening, it was very easy to imagine Jane on her vacation, moving free and happy, under obligation to no one.

Scott Joplin now has his own gravestone at Saint Michael’s cemetery. Every April 1st, musicians gather to give a concert on the anniversary of his death. His grave is not far from my house in Jackson Heights and I had intended to visit this year. But St. Michael’s is in East Elmhurst, Queens, and as I write this, Queens has more COVID-19 cases than the entire state of California. East Elmhurst is collapsing under the burden of cases. Many local stores are closed for the duration; someone has spray-painted crude sharks on their gates with a punchy, epithet laden message to the virus. No one is moving free and happy in Queens right now. But hopefully by next year, we’ll be back to a “rag-time life.”

Read more by Mariah Fredericks!

Mariah Fredericks was born and raised in New York City, where she still lives with her family. She is the author of several YA novels. Death of an American Beauty is her third novel to feature ladies’ maid Jane Prescott.