by Nick Tabor

It’s hard to believe that when Zora Neale Hurston started on her book Barracoon, which would turn out to be one of the greatest achievements of her illustrious career, she was still an undergraduate student. She had never published anything longer than a short story.

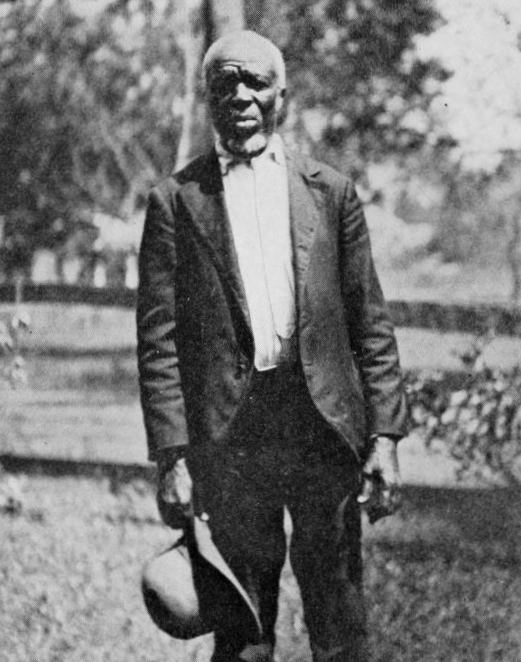

Barracoon is the true story of Cudjo Lewis, a West African native who survived the voyage of

the Clotilda—the last vessel ever brought to the United States as part of the transatlantic slave trade.

Barracoon also narrates the way Cudjo and his fellow shipmates established a community after the Civil War, where they spoke their own languages and appointed their own leaders—a place originally called African Town. It remains intact (with its name shortened to Africatown), and it’s the only community in the US ever founded by West Africans who had personally survived the Middle Passage.

When Hurston interviewed Cudjo, in 1927 and 1928, he was in his eighties and was still living in African Town. But all the other local survivors had passed away, and Cudjo himself was frail. For the sake of future generations, it was critical that Hurston recorded his memories when she did.

But the project was not Hurston’s idea alone. It almost certainly wouldn’t have happened outside of the broader context of the Harlem Renaissance. It’s appropriate to regard the book as one of the masterpieces of that literary movement, along with Jean Toomer’s novel

Cane and Langston Hughes’s early poetry. Thinking about it this way also underscores the broader relationship between Harlem and Africatown—a relationship that has persisted in other forms ever since.

The Harlem Renaissance was a flowering of art, literature, and scholarship that dealt with the African American experience. One priority of its leaders was to collect Black folktales from members of Cudjo’s generation while they were still living. Cudjo himself first became known to Harlemites in 1925, when the book

The New Negro: An Interpretation, the movement’s cornerstone text, was published. One of its chapters consists of Cudjo narrating an African folktale about a turtle and an eagle. He’d been interviewed by the young writer Arthur Huff Fauset, who transcribed his words more or less verbatim.

At the time, Hurston was studying anthropology at Barnard College—where the curriculum, she told a friend, was “as full of things a writer could use as a dog is full of fleas.” She had an obvious knack for the discipline. “Almost nobody else could stop the average Harlemite on Lenox Avenue and measure his head with a strange-looking, anthropological device and not get bawled out for the attempt,” her close friend Langston Hughes wrote—“except Zora, who used to stop anyone whose head looked interesting, and measure it.” Her playful, disarming manner made her a natural interviewer.

She was also a social fixture among Harlem intellectuals. One of her own short stories, “Spunk,” was included in

The New Negro. In 1926, as her graduation approached, she received a grant to spend several months on the Gulf Coast, collecting as much Black folklore as she could. Her mentor, Franz Boas, evidently knew about Cudjo from

The New Negro, and he specifically told her to find Cudjo and produce a fuller account of his story. She did, and the resulting article was published in

The Journal of Negro History.

Several of the dominant figures in the

Harlem Renaissance were financially supported by Charlotte Osgood Mason, a quirky white woman who lived in a penthouse near 54th Street. Mason was an amateur anthropologist herself, and she had the idea that West African cultures—or “the creative impulse throbbing in the African race,” as she put it—could cure the ills of modern American society, which she believed was stifled by commercialism and industry. For a starving young poet, being supported by Mason was like receiving a Guggenheim or MacArthur fellowship. In most cases, the only formal condition was that recipients had to keep her identity a secret and refer to her simply as “Godmother.” After Mason read Hurston’s article on Cudjo, she commissioned the young writer to go back to Mobile and write a book-length manuscript about his life.

The bulk of Hurston’s interviews with Cudjo happened in 1928. Traces of Mason’s involvement can be seen throughout

Barracoon—starting with the dedication. “To Charlotte Mason,” it reads. “My Godmother, and the one Mother of all the primitives, who with the Gods in Space is concerned about the hearts of the untaught.” Mason also played a role in getting Cudjo to open up. By February of 1928, if not earlier, she was sending him a monthly allowance to pay for his fruit and tobacco. Hurston notes that one day she opened their conversation by talking about the white woman in New York who had taken an interest in him. Cudjo liked hearing about Mason; he said Hurston should let her know that he wanted to please her.

It’s hard to imagine anyone rendering Cudjo’s story in a more poignant way than Hurston did. One reason is that she presented it in his own voice, in prose that kept his pronunciations intact. However, this decision was the main factor that prevented the book from being published within Hurston’s lifetime, according to letters she wrote to Mason. White book editors, she said, didn’t believe a book written in “dialect” could ever attract a large audience.

Barracoon was finally published in 2018. The book immediately became a

New York Times bestseller, and it’s still the best single primary source we have on the

Clotilda and the founding of African Town. (It also provided a narrative backbone for the Netflix documentary

Descendant, as descendants of Cudjo and other shipmates read portions of the book on camera.)

Almost a century after Hurston first visited Mobile, Africatown is struggling to survive. It’s surrounded by heavy industry, and many residents believe pollution in the neighborhood has caused a cancer epidemic. However, over the last few years, it’s received international media attention, and there are efforts underway to transform it into a destination for heritage tourism.

The first person to read a draft of

Barracoon may have been Alain Locke, who is widely regarded as the dean of the Harlem Renaissance. He said it was due to “providence” that Hurston had been put on the assignment. These days, it’s common to hear Africatown residents and their allies say that “something spiritual is happening”—because factors seem to be lining up in their favor, in uncanny ways. Reading Locke’s remark about

Barracoon, it’s hard not to hear an echo.

Nick Tabor is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in

New York Magazine,

The New Republic,

The Washington Post,

Oxford American,

The Paris Review, and elsewhere.

Africatown is his first book. He lives in New York.

Tags:

Africatown,

Barracoon,

Clotilda,

Nick Tabor,

Zora Neale Hurston

stree

stree stze

stze