by Jess Montgomery

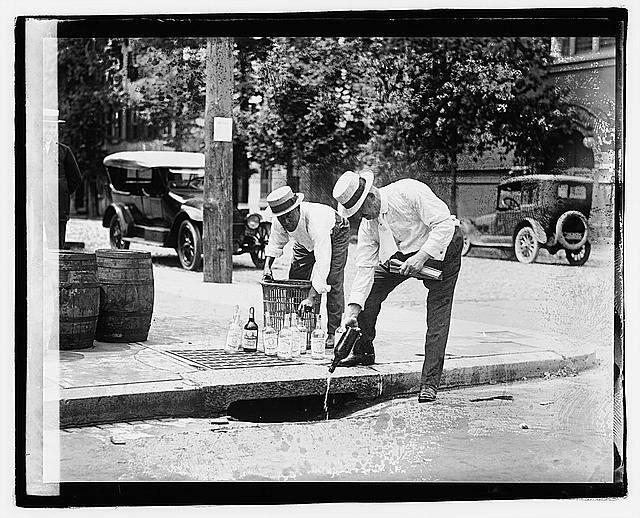

The first images that usually pop to mind with the word “Prohibition” are of dapper men and women in speakeasies enjoying illicit libations… until police officers brandishing guns and batons rush in to raid the joint and break up all the fun.

But as I mention in my Author’s Note to The Stills, the third novel in my Kinship Historical Mystery series set in 1920s Appalachia, Prohibition was a complex issue, driven by social, religious, and political issues.

Now, we often see it as a quaint, failed experiment, but in the years leading up to Prohibition, and for many years after, passionate beliefs led to the passage of the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1919 banning the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcoholic beverages and of the Volstead Act which laid out the terms for enforcing the law of the amendment.

In fact, many scholars consider Prohibition to be the United States’ first ‘wedge’ issue. Politicians and lobbyists on either side (“dry,” meaning pro-Prohibition, or “wet,” meaning anti-Prohibition) used the issue as proxy for other issues—from women’s suffrage to equal rights for Black Americans—and as a way to divide Americans over these issues, fomenting dissension between the sides, rather than discussion, with the hope of ‘their’ side winning.

Throughout my series, bootlegging and Prohibition are a necessary part of the background of my stories. And given that the Kinship mysteries are set in Appalachia, of course moonshining is also part of the world I write about.

Personal note: My father, who later in life was a preacher, passed away in 2018, but a few years before, when I told him about the first Kinship novel I’d just started writing, I mentioned that, well, moonshining might be a part of the story. I expected him to look a bit shocked, but instead he got a twinkle in his eye, and said, ‘now let me tell you about how I might have visited my uncle’s still one time when I was a teenager…’ Then, Dad, who was a machinist most of his working life and brilliant at anything mechanical, described how a still works.

What’s more, Prohibition didn’t turn the country “dry” all at once. Many areas, including the one in which I set the Kinship novels, were dry on a county-by-county basis for years before Prohibition—and remained so for years after.

So at the beginning of The Stills my protagonist, Sheriff Lily Ross, would have been quite familiar with the reality of moonshining, as well as ‘dry’ versus ‘wet’ attitudes even before Prohibition became national law.

Yet, I knew this third novel in my series would be set in 1927, and that it was time to bring Prohibition, and all its complexities, to the foreground of the plot and character motivations in this story.

Wondering how 1927 might be different in terms of Prohibition than the years immediately before or after it, I started digging.

I was surprised to discover that as Prohibition wearily carried on, sixty million gallons of industrial alcohol were stolen each year (give or take a few gallons here and there) to be reclaimed to make potable alcohol for thirsty ‘wets’ at speakeasies and at home. So, by 1926 the Federal Government required industrial alcohol to be denatured with bitter chemicals, rendering it undrinkable.

For every move the government half-heartedly made to enforce Prohibition (the law was so hard to impose, and there were so many loopholes, that it was only spottily implemented, and often unfairly or at greater human cost than the problems of alcoholism ‘dries’—in some cases sincerely, and in others as an aforementioned wedge issue—were trying to solve), crime syndicates had a countermove.

In this case, it was to hire chemists to ‘renature’ the stolen industrial alcohol.

The Federal Government’s response was to make industrial alcohol even more deadly, methyl alcohol being the most deadly. “Blind drunk” was a true possibility. So was dying from drinking methyl alcohol.

One senator, Edward I. Edwards of New Jersey, called the federal government’s actions “legalized murder.” But as reports emerged in 1927 of drinkers becoming seriously ill or dying because of methyl alcohol, Wayne B. Wheeler, of the Anti-Saloon League, shrugged off anyone drinking industrial alcohol as committing “suicide,” and said “to root out a bad habit [meaning drinking alcohol of any kind] costs many lives and long years of effort.”

A calculated, callous response, since of course a drinker would have to know that the industrial alcohol available in 1926 is now far more poisonous and deadly than in 1925. Knowing that would require a way of being informed—news reports in newspapers and on the radio. And that, in turn, requires access to those sources and the ability to read, which depends on the drinker’s station in life.

To be precise, the Federal Government did not directly give poisoned alcohol to imbibers. But it did purposefully poison the industrial alcohol supply, knowing full well that foolhardy or unwitting drinkers would consume the dangerous and deadly alcohol. The goal was to scare people out of drinking at all. However, that scare tactic came at a great cost. It’s estimated that by the time the 21st Amendment put an end to national Prohibition in 1933, some 10,000 people died as a result of the government’s policy.

Denatured or industrial alcohol still contains about 10 percent methyl alcohol to this day. As of 2021, thirty-three states in the United States allow local municipalities to decide if they wish to be ‘dry.’ Kansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee are ‘dry’ states by default, but allow local municipalities to decide if they wish to be ‘wet.’

Now outside the Anti-Saloon League Museum in Westerville, Ohio, housed where the Anti-Saloon League once operated, is a fourteen-foot-tall bronze sculpture called “The American Issue” depicting a wedge splitting a rock in half to symbolize and recognize Prohibition as the United States’ original wedge issue.

Though the motivations and actions of those involved in Prohibition were nuanced and complex—not as simple as simply “pro or con,” or “wet vs. dry”—one would hope that we’d learn from history, from the tragic and unnecessary deaths of the Prohibition era, whether from a horrific government policy used against the public it was supposed to protect, or from criminal syndicates defying the law of the land, particularly as we face other public health issues such as the ongoing opioid crisis.

Learn More!

Which states are still “dry” in 2021?

What was the Anti-Saloon League?

Why was The American Issue Sculpture installed?

What was the Federal Government’s official policy on industrial alcohol?

Read More from Jess Montgomery!

Jess Montgomery is the “Literary Life” columnist for the Dayton Daily News and writes a new Writer’s Digest magazine column, “Level Up Your Writing (Life).” Based on early chapters of the first in the Kinship Series, The Widows, Jess was awarded an Ohio Arts Council individual artist’s grant for literary arts and named the John E. Nance Writer-in-Residence at Thurber House in Columbus. She lives in her native state of Ohio.