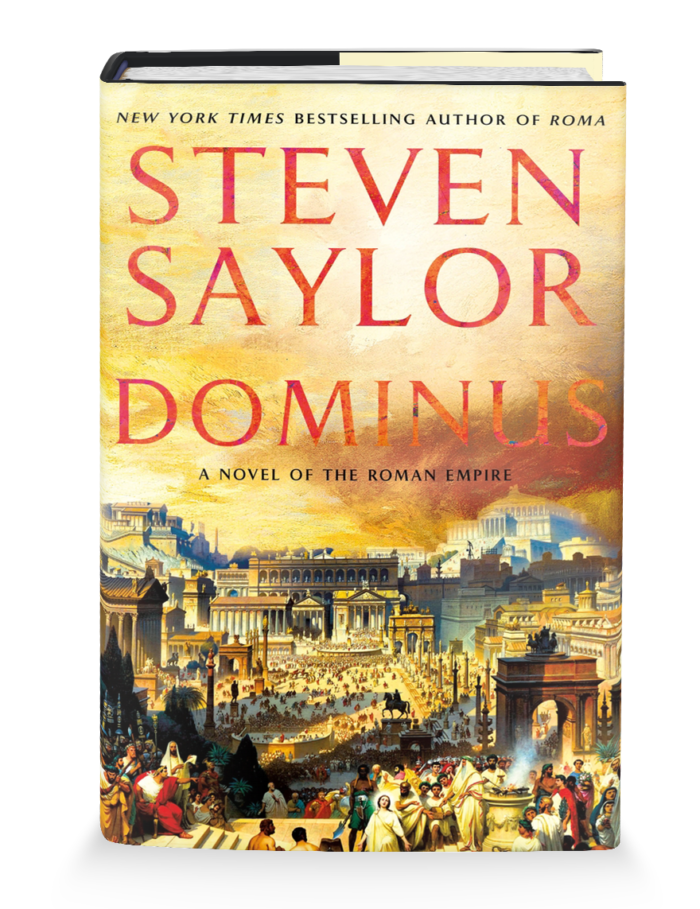

Spanning 160 years and seven generations, teeming with some of ancient Rome’s most vivid figures, Steven Saylor’s novel Dominus brings to vivid life some of the most tumultuous and consequential chapters of human history, events which reverberate still. Read an excerpt below.

I’m afraid our daughter might die . . .

These words of his wife rang in the ears of Lucius Pinarius as he stepped inside the Senate House, holding the hand of his four-year-old son. Surely the situation was not as bad as that, he thought. What were Pinaria’s symptoms, after all? Sleeplessness, lethargy, loss of appetite, an irregular pulse, mental distraction—hardly the signs of a plague, and rather mild if the problem was an infestation by some evil spirit. On the other hand, Lucius’s wife had cited a number of examples of friends and loved ones who had died from symptoms far less severe than those of their teenaged daughter, with the end sometimes coming quite suddenly. Pinaria’s illness had already lasted for at least two months, de- spite the efforts of three different physicians to cure her. Today a new physician was coming to examine Pinaria, a young fellow from Pergamum recommended by one of Lucius’s colleagues in the Senate.

But first, Lucius would begin the day as he tried to begin every day, with an offering to the goddess who presided over the vestibule of the Senate House. As he and little Gaius stepped inside and the tall bronze doors closed behind them, the goddess loomed over them, her body much larger than that of any mortal, her massive wings spread wide, one arm extended over their heads to offer a laurel wreath too big and

surely too heavy for any mortal to wear. The bronze statue was painted with such skill and delicacy that the laurel leaves looked freshly picked and the winged goddess appeared ready to leap from her high pedestal at any instant. The soft light from high windows enhanced the illusion. Little Gaius, who had never been inside the Senate House, stared upward at the statue of Victory. He made a noise between a gasp and a whimper, and grabbed hold of his father’s toga.

There was no one else in the vestibule. Except for the goddess, they were quite alone. The slightest sound echoed from the marble walls.

Lucius laughed softly and touched the boy’s blond curls, which gleamed by the light of the pyre that burned low on the marble altar before the statue. “Have no fear, my son. Victory is our friend. We worship and adore her. In return, she has shown great favor to us. A senator never enters this chamber without first pausing here at her altar to light a bit of incense and say a prayer. Smoke is the food of the gods, and there is no smoke sweeter than that of incense.”

As he touched a bit of incense to the flame and watched it smolder, he looked up at the statue and whispered, “Sweet Victory, beloved by all mortals, bestow your favor on our esteemed emperor Verus in his campaign against the Parthians. Scatter his enemies before him. Keep safe the legions under his command. Grant them many conquests and much plunder. And when their work is done, see the emperor Verus and his troops safely home so that they may parade in triumph up the Sacred Way. I give voice to the prayers of all Romans everywhere. We all bow our heads before you.” He glanced down at his son, whose head was already bowed. “And also, sweet Victory, for myself and for my family I ask a much smaller favor—that you give your blessing to my endeavor today. Let the physician be skilled and honest. Let him restore my daughter to full health.” And let him not be too expensive, Lucius thought, but did not speak the words aloud. He did not believe in bothering the gods with trivialities.

Behind them, the massive bronze doors creaked open. The man who

entered wore a toga with a purple stripe, like that of Lucius. He saw little Gaius and smiled.

“The boy’s first visit, Senator Pinarius?”

“Yes, Senator . . .” Lucius knew the man only from meetings, and could not think of his name. When on official business he had a slave at hand to whisper such details in his ear, but his small retinue of servants was waiting for him outside.

“I thought so, from those wide green eyes. A senator’s son never forgets his first time inside the Senate House. She’s quite impressive, eh, young man?”

“Yes, Senator.” Gaius had been taught always to answer his elders and to address them respectfully.

“His first visit, but far from his last, I suspect. Do you want to grow up to be a senator like your father, young man?”

“Yes, Senator!”

Lucius took Gaius by the hand and stepped aside to allow the man to make his own offering at the altar. They passed through the door, which was still ajar, and onto the broad porch of the Senate House. Father and son blinked at the bright sunshine. Below them, in the open spaces of the Forum, men stood in groups, loudly conversing. Slave boys ran about, carrying messages or running errands for their masters. After the hush inside the Senate chamber, the noise of the Forum on a busy morning was striking, and to Lucius’s ears quite pleasant. The noise of the Forum was the pulse of the city, and on this morning it was neither hectic nor sluggish, but indicated the normal functioning of the grandest, most powerful, and most noble city on earth.

If only his daughter could be as healthy as Rome seemed to be on this fine spring morning!

Copyright © 2021 by Steven Saylor.

Steven Saylor is the author of the long running Roma Sub Rosa series featuring Gordianus the Finder, as well as the New York Times bestselling novel, Roma and its follow-up, Empire. He has appeared as an on-air expert on Roman history and life on The History Channel. Saylor was born in Texas and graduated with high honors from The University of Texas at Austin, where he studied history and classics. He divides his time between Berkeley, California, and Austin, Texas.