by Bill Glose

To fully understand a specific war, one must not only study the casualties and capitulations that come with every scrap of fought-over land, but also the lingering effects on those called upon to fight its battles. War does not end once peace is declared; it bleeds into the future.

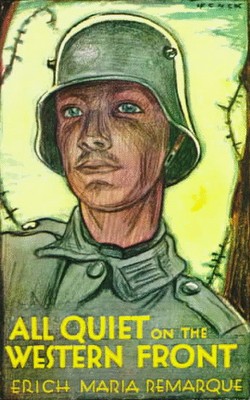

Erich Maria Remarque portrays this lasting impact in All Quiet on the Western Front, an incredible novel about the horrors of World War I told from the perspective of a German soldier. The main characters are a class of young boys who enlist after getting caught up in the fervor of war. In the trenches, their shiny ideals are quashed by the muddy truth of combat, and they are likewise changed. Here, the youthful protagonist, Paul Bäumer, reflects on how different a person he’s become:

I imagined leave would be different from this. Indeed, it was different a year ago. It is I of course that have changed in the interval. There lies a gulf between that time and to-day. At that time I still knew nothing about the war, we had only been in quiet sectors. But now I see that I have been crushed without knowing it. I find I do not belong here any more, it is a foreign world.

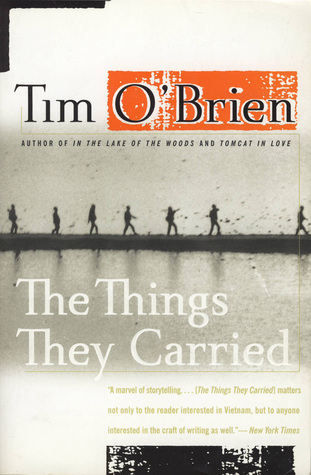

Combat is a house on fire that brands everyone who enters. No one escapes without carrying its mark forever after. In Tim O’Brien’s masterful story collection, The Things They Carried, the American soldiers who populate his stories are as confused about the fighting in Vietnam as the protesters who vilify them. The traumatic experiences they witness and participate in haunt them for years to come.

Twenty years later, I can still see the sunlight on Lemon’s face. I can see him turning, looking back at Rat Kiley, then he laughed and took that curious half step from shade into sunlight, his face suddenly brown and shining, and when his foot touched down, in that instant, he must’ve thought it was the sunlight that was killing him. It was not the sunlight. It was a rigged 105 round. But if I could ever get the story right, how the sun seemed to gather around him and pick him up and lift him high into a tree, I could somehow re-create the fatal whiteness of that light, the quick glare, the obvious cause and effect, then you would believe the last thing that Curt Lemon believed, which for him must’ve been the final truth.

For veterans returning from a decade of fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, the trauma of war is further compounded. In addition to the stress of actual combat and the continual threat of IEDs for every inch of roadway traveled, the same soldiers were redeployed to the Middle East for numerous tours of duty. An enduring battle fatigue followed them home, where a heightened state of stress and vigilance toward imagined threats alienated soldiers from their families. The combat zone became their new norm and peaceful homes became where they felt jittery and out of place.

This outsider sense was something I tried to capture in All the Ruined Men, a collection of linked stories about a squad of soldiers struggling to fit in at home after years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan. Here is one passage where a soldier named Brendan Mueller tries to reconnect with his wife and their three-year-old child:

Sophia says I spoil Chrissie, but what choice do I have. Absent half her life, I have to work twice as hard to make the time count. A paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division, I go where the Army sends me. Last deployment was eleven months in Iraq. Before that was six in Afghanistan. Both times, my first week home, I was a stranger to Chrissie. When I’m gone, I live in hallway pictures and on the computer screen as her mother Skypes. When I’m finally there in the flesh, it’s hard for her young mind to connect the two-dimensional image with the three-dimensional reality. My face might wear the same brown hair buzzed high-and-tight and the same scar bisecting my left eyebrow, but it still seems foreign, it still seems wrong. Her tiny body will squirm when I hold it against my wiry frame, her own arms squeezing George in a death grip as she struggles to break free. Months later, after she’d used to me being around, I’m off again. Then it’s my leg she’s clutching as she wails, Don’t go, don’t go, [her stuffed toy] tossed aside in a heap.

In the chaos of war, soldiers function by relying on training. No time to think, just act. After coming out the other end alive, that’s when soldiers replay what happened and feel the weight of consequence, recriminations whispering to them in the dark of sleepless nights. As a combat veteran, I can attest that the battle continues long after the last shot is fired. The anger cultivated in training has no proper outlet in the civilian world. Oftentimes, it comes out in explosive rages, as shown here as Muller attacks the boyfriend of his teenage daughter, the same girl from the earlier story who had clung to his leg as a toddler:

Brendan launches himself at the kid, and when the boy tries to wrap him up, Brendan grabs his long hair and yanks hard enough to induce whiplash. He slams the boy against the wall, one hand on his throat, squeezing.

Get off him, Dad, Chrissie screams, clawing at his arm. Get off!

He releases the boy’s neck and flattens his hand on his chest, pressing him against the duck-patterned wallpaper. Stay right there…

Chrissie marches out. You can’t do this, Dad. I don’t see you for three years, and now you’re kicking down doors. Who does that?

Me and every soldier I served with.

You’re a total dick, you know.

Yeah, he says, I know.

Eruptions of volcanic anger are nothing new. For millennia, one group of people has waged war on another and their combatants have suffered the aftermath of what they’ve been called on to do. Over time, advancements in weaponry have multiplied the ways people can be killed and wounded. At the same time, upgrades in armor have made it possible for soldiers to survive attacks that would have killed them before. Instead of dying, they lose limbs, are maimed, or suffer traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) from concussive explosions. Between 2000-2018, US soldiers suffered 225,144 TBIs. Once returned home, they not only feel different, they often are, even if that change is not physically visible to others.

War is gruesome, its toll unimaginable. It demands payment in flesh, but it also carves out a piece of each soldier’s soul. Coming home afterward can be just as scary as going to war in the first place. It’s a struggle, but life always is. It’s been said that you cannot understand someone until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes. No book can fully convey the anguish that soldiers carry home from war. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t read them anyway and try the best we can to understand.

Bill Glose is a combat veteran and former paratrooper. He is the author of several books of poetry, including Postscript to War and Virginia Walkabout. His magazine articles, stories, poems, and essays have appeared in numerous publications, including The Missouri Review, The Sun, Narrative Magazine, and The Writer. Glose received the F. Scott Fitzgerald Short Story Award, the Robert Bausch Fiction Award, and the Dateline Award for Excellence in Journalism. Glose was named the Daily Press Poet Laureate in 2011 and featured by NPR on The Writer’s Almanac in 2017.