by Kate Mosse

The television series The Crown, written by Peter Morgan, inspired by the history of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II from 1947 to the present day, is hugely popular on both sides of the Atlantic. Fantastic actors have played some of the key characters—including Claire Foy and Olivia Coleman as Queen Elizabeth, Mission Impossible star Vanessa Kirby (who starred in Ridley Scott’s 2021 television adaptation of my novel Labyrinth) as Princess Margaret and Matt Smith as Prince Philip. In Season 4, which is airing now, we have Gillian Anderson as Margaret Thatcher and newcomer Emma Corrin as Lady Diana Spencer. But this latest series has been making newspaper headlines for all the wrong reasons. Commentators have lined up on both sides to either support or condemn it for its historical inaccuracy, for its bias, for its playing hard-and-fast with the truth. It even moved a British politician to issue a statement in the House of Commons demanding the show should carry a warning that it is fiction, not fact.

This level of reaction says a whole lot about the state of things—a global pandemic, rumour and counter-rumour, a world where the phrase ‘fake news’ is thrown about by anyone who doesn’t agree with what’s being said. We are watching real, vital, and life-making history being played out on our screens every night. I do think it can be dangerous when the lines between history and drama become blurred, especially when dealing with contemporary events and the protagonists are still alive. But here’s the thing: this creative interpretation of real people’s lives or key events in history is nothing new. Historians, from every nation in the world, have been arguing about key moments in history, and attributing motives to key players in history, for as long as there have been history books to read.

Simon Schama once described the Greek historian Herodotus as a ‘shocking liar’. It’s often a matter of whose side you’re on—the history of the American Revolutionary War looks very different from Alexander Hamilton’s point of view in New York than from that of King George III going mad in London. Or, for instance, the contrast of World War II as seen through the eyes of the Axis powers as opposed to the Allied forces’. But it’s also that though we challenge politicians and commentators now—and witness how some of them are lying—we naively tend to assume that historical record is always factual, that courtiers and leaders of the past were truthful rather than also having a personal agenda. Well, let’s put history in the dock. Because the truth is that we should no more rely upon written testimony from the 16th century without interrogating it than we should accept everything we read on our tablets, phones, or in the daily newspapers as unbiased.

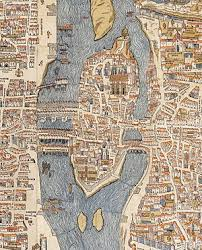

There’s no better historical example of how the same set of facts can be woven to tell a radically different story than the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in Paris 1572. This became known as the most notorious incident in the Wars of Religion which raged between Catholics and French Protestants— known as Huguenots—in France between 1562 and 1594. It’s an incident that changed the course of European history, marked the resumption of religious civil war in France, and lies at the heart of my latest historical adventure novel, The City of Tears.

So, what do we know for certain? We know that France was bitterly divided and had been trapped in a cycle of civil religious war and uneasy peace for a decade. We know that there was a vicious battle for power going on at Court between the French Crown, led by Catherine de’ Medici, mother to the weak Charles IX, between the powerful ultra-Catholic Guise family, led by Henry of Guise, and between the aristocratic Huguenot leadership, lead by Admiral de Coligny. We know that in the spring of 1572 the Queen Mother had negotiated a royal alliance with the Queen of Navarre, the devout Huguenot Jeanne d’Albret, between her daughter, Princess Marguerite de Valois (and alleged lover of Henry of Guise), and Albret’s son, Henry of Navarre of the Bourbon dynasty. We know that the Queen of Navarre died in Paris in June, and rumours were rife that she had been poisoned by Catherine de’ Medici. We know that, despite all the barriers to a Catholic marrying a Huguenot, the royal wedding went ahead on the 18th of August at the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris. We know that there was an assassination attempt two days later on the life of Coligny, the shot taken from a house owned by the Guise family. We know that, before the killing started, some houses were daubed with white paint and armed soldiers tied white kerchiefs on their arms to mark them out as Catholic. We know that chains were dragged across the narrow medieval streets and the gates of the city of Paris bolted shut to trap everyone inside. We know that, as the alarm bells started to ring out from the church of St Germain l’Auxerrois, the parish church of the Louvre Palace, in the early hours of the morning of St Bartholomew’s Day, August 24th, Guise stormed Coligny’s dwelling with an armed guard, murdered the elderly Admiral, and held his severed head up for his men to see. This was the signal for a mob to rampage through the streets, murdering women, children and men, citizens and ordinary people, until the streets ran red with blood and the skylight of Paris burned bright with fire. We know that, although Henry of Navarre himself was spared, the Huguenot leadership was decimated or forced to convert to Catholicism. It would take hundreds of years for France to recover from the treachery and perfidy of that night.

The bones of the event and those leading up to it have been picked over by countless historians, by philosophers and theologians, specialists in warfare, military tacticians, biographers of the major players—Navarre, Medici, Albret, Guise, the Valois family, academics expert in the religious wars that swept through Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But yet, even nearly 450 years later, one question still remains: who gave the order for the massacre?

This gap in verifiable knowledge is what we historical writers live for. While it’s crucial always to respect the history, to research the facts, to read historians of all and differing viewpoints, to write with authenticity and integrity, nonetheless there are moments of opportunity where a novelist can slip between what is known and what can only be imagined. This is where we set our stories. In The City of Tears—the second of my historical adventure series telling the story of a three-hundred-year-old feud between two families, one Huguenot and one Catholic—the tragedy of a missing child and a family destroyed by that trauma is played out against the backdrop of this real history. When I started writing the novel, which begins ten years after The Burning Chambers finishes—I knew my first family, the Joubert family, would be present in Paris to witness the royal wedding. What I didn’t know was which of them would survive and who would be lost, which of their friends or enemies would escape, nor what the consequences would be. I didn’t know then that the Joubert family were at the beginning of a quest that would take them from Paris to exile in Amsterdam, that their enemies would continue to pursue them, and that the story would end in Chartres in 1594. An underground reliquary, a priest driven mad by his desire for revenge, the grief of a child not found… the story spirals out from that one August night in Paris.

So, who should be in the dock? Who do I think is responsible for the massacre and the 70,000 odd deaths that followed in copy-cat massacres throughout the length and breadth of France? The answer is hidden within the pages of The City of Tears…

Kate Mosse is a multiple New York Times and #1 internationally bestselling author with sales of more than seven million copies in thirty-eight languages. Her previous novels include Labyrinth, Sepulchre, The Winter Ghosts, Citadel, and The Taxidermist’s Daughter. Kate is the Founder Director of the Women’s Prize for Fiction, a Visiting Professor at the University of Chichester and in June 2013, was awarded an OBE for services to literature. She divides her time between the UK and France.