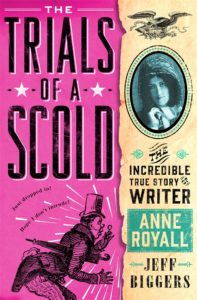

by Jeff Biggers

Bloody feet, sisters, have worn smooth the path by which you have come hither.

Abby Kelley Foster, National Women’s Rights Convention, 1851

In the summer of 1829, more than a century after Grace Sherwood had been plunged into the Lynnhaven River in Virginia in what is generally considered the last American witch trial, a bedraggled Anne Royall took the stand at the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia to face charges of being an “evil disposed person” and a “common scold.”

The US district attorney had conjured the charges from an ancient English common law that had long been dismissed in England as a “sport for the mob in ducking women,” especially for older women, as a precursor in trials for witchcraft.

The 60-year-old Royall, godmother of the muckrakers, grinned in the seat of the accused for defending free speech and freedom of the press. According to the court’s research, England had curtailed the conviction of “common scolds” in the late 1770s at the same time it ceased hanging women and gypsies as witches.

Not so in our nation’s capital. For the throng of reporters that crowded the suffocating courthouse that summer, the United States v. Anne Royall and the “vituperative powers of this giantess of

literature,” according to the New York Observer would become one of the most bizarre trials in Washington, DC.

Anne Royall was no stranger to trials. One of the most notorious writers of her time, she had shattered the ceiling of participation for politicized women a generation before Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony entered the suffrage ranks and issued the “voice of woman” into the backroom male bastions of banking and politics nearly two centuries before Hillary Clinton and Elizabeth Warren.

She had paid dearly for her groundbreaking role as a satirist and muckraker.

Nearly half a century after Royall’s death in 1854, the Washington Post would stretch a headline across its pages with a reminder of her still haunting and relevant legacy: “She was a Holy Terror: Her Pen was as Venomous as a Rattlesnake’s Fangs; Former Washington Editress: How Ann Royall Made Life a Burden to the Public Men of Her Day.”

The Post’s backhanded compliment of Royal’s pioneering muckraking journalism, however, missed her defining element in the art of exposé nearly a century before President Teddy Roosevelt

The Post’s backhanded compliment of Royal’s pioneering muckraking journalism, however, missed her defining element in the art of exposé nearly a century before President Teddy Roosevelt

in 1906 famously decried “the man with the muck rake”: her take-no-prisoners humor in defense of the freedom of the press at any cost.

“She could always say something,” declared a New England editor, “which would set the ungodly in a roar of laughter.”

Anne Royall knew how to make her readers laugh, and laugh at men a dangerous talent, especially for a freethinking woman who rattled the bones of Capitol Hill and made Congress “bow down in fear of her” as the whistleblower of political corruption, fraudulent land schemes, and banking scandals, and as the thorn in the side of a powerful evangelical movement sweeping across the country.

She didn’t simply have a second act in life; she had three or four or five. Born in Maryland in 1769, her freethinking politics had been shaped in the Virginia backwoods library of her Freemason and Revolutionary War-hero husband, William Royall. Rejected by his family as a lower-class concubine, Royall was left penniless when her husband’s estate was finally adjudicated in the courts in 1823.

In debt but defiant as ever, Royall reinvented herself and launched a literary career at the age of 57. She announced her intention to publish a book on her recent sojourn in Alabama as a “serpent-tongued” traveling writer in the 1820s, introducing the term “redneck” to our American lexicon and a Southern and frontier view to an emerging national identity, and challenged the prevailing mores of “respectable” Christian women through one avenue suddenly available: the printing press.

Traipsing across the rough country as a single woman, she quickly published a series of “Black Books” that provided informative but sardonic portraits of the elite and their denizens from Mississippi to Maine. Her Black Books became prized possessions, if only for the delight of devastatingly funny descriptions of her “pen portraits.” Power brokers sought out her company

or locked their doors. President John Quincy Adams called her the “virago errant in enchanted armor.”

The anti-Mason religious fervor sweeping the Atlantic Coast and across the frontier infuriated Royall and prodded her to sharpen her witty pen in a self-appointed role as journalist and judge. The Second Great Awakening had provided the nation with one of its most critical opponents: dour and reactionary Presbyterians intent on establishing a Christian Party and transforming American politics and Royall took them on. “The missionaries have thrown off the mask,” she warned. “Their object and their interest is to plunge mankind into ignorance, to make him a bigot, a fanatic, a hypocrite, a heathen, to hate every sect but his own, to shut his eyes against the truth, harden his heart against the distress of his fellowman and purchase heaven with money.”

Royall may have limped after a brutal attack in New England, been scarred from a horsewhipping in Pittsburgh, and lamented being chased out of taverns on the Atlantic Coast, but she relished the attention in the nation’s capital. Andrew Jackson’s secretary of war, John Eaton, would soon testify on her behalf.

JEFF BIGGERS is an American Book Award-winning journalist, cultural historian and playwright. He is the author of several works of memoir and history, including Reckoning at Eagle Creek, which was the recipient of the David Brower Award for Environmental Reporting. His award-winning stories have appeared in The New York Times, Washington Post, The Atlantic, and on National Public Radio. Biggers is a regulator contributor to Al Jazeera America, Huffington Post, and Salon.