WCAG Heading

by Hannah Kimberley

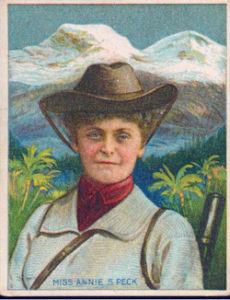

I first came across Annie Smith Peck on a black-and-white poster from an antiques shop in 2007. The image displayed a woman wearing a long tunic sweater, canvas knickerbockers, and leather boots. She sported a hat fastened under her chin and a rope tied about her waist. Her elbow rested on an ice ax. The poster read a woman’s place is at the top and included the name “Annie Smith Peck” at the bottom. Below her name were Peck’s birth and death dates and a description of who she was: “Mountain Climber, Scholar, Suffragist, Authority on North-South American Relations.” Her face presented a slight half-smile as she stared into the distance, as if she were aware of some secret to which I was not yet privy.

I would eventually learn that Peck was a daughter of the 1800s, a scholar before her time, and a teacher. She was among some of the first female undergraduates from the University of Michigan, eventually earned her master’s degree, and became the first woman to attend the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, Greece. She was an international lecturer and a record-setting mountaineer during an era when women climbers were expected to scale peaks in skirts. Annie Smith Peck was one of the most accomplished women of the twentieth century whom I had never heard of. She was an ultimate underdog, a woman who singlehandedly carved her place on the map of mountain climbing and international relations.

…

With horses for each member of the ragtag expedition and mules for the baggage, Annie Smith Peck and Volkmar set out for the snow line, escorted by the lieutenant, as the townsfolk watched on. They stopped at Pedro’s house, in the closest village to the base of the mountain, and had lunch. From there, they rode on until they reached a good spot to camp, at about 14,000 feet.

Once again, Annie Smith Peck spent a cold night at the foot of another mountain, where three sets of wool undergarments weren’t enough to keep her warm.

The next day, they studied the mountain through binoculars and made plans for their first strike. The snow was different from what Annie Smith Peck was used to on Huascarán. There was no giant glacier gently flowing onto the rock at the snow line. Instead, the glacier slowly diminished toward the rocks in the form of snow. In front of them was a steep slope.

To the left, the way was less steep and it looked like they might be able to work their way along a level ridge and then move steadily back toward the right and up. Carpio, Pedro, Domingo, and Julian all opted for taking the roundabout way, but Volkmar insisted on attacking the steep slope head-on. Annie reluctantly followed Volkmar.

The snow became solid and icy as Annie Smith Peck and Volkmar moved along. The walking was hard. Annie spotted a path that was less icy and moved away from Volkmar in that direction, while Volkmar continued straight up. As Annie Smith Peck moved along, the snow was so hard that she was incapable of striking into it with her ice ax. She blew her whistle to signal Volkmar, who came to her aid and helped with cutting steps into the ice.

Annie noticed that the rest of her crew had stopped, so she decided to move toward them. The snow grew softer as they moved along, and they began to sink in as they stepped. Once again, Volkmar resisted Annie Smith Peck’s directions, but eventually he followed along.

When they met up with the rest of the crew, everyone was tired and ready to camp. Annie was disappointed to be stopping at only four p.m., but she acquiesced. As soon as the tent was pitched, Volkmar huddled in the corner and fell fast asleep. As always, the responsibilities of attending to the unpacking, lighting the stove, boiling water, and cooking were relegated to Annie Smith Peck. She reflected on her usual habit of domestic duties even when she was in the wilderness:

This was my weary time always. I did not carry anything as did the others, but every night while they were resting my labors continued. The stoves burning kerosene with a gas flame must be lighted with alcohol and required constant attention. A kettle full of snow would supply about two inches of water. Usually all wanted a drink, for which this barely sufficed. More snow, more and more was needed, to melt, then boil. And it wouldn’t boil. At last a little steam; in the end, perhaps after two hours, there were really bubbles. The men who had taken naps and eaten part of their suppers now enjoyed a cup or two of hot tea.

She would repeat the entire process again the next morning—boiling water and packing supplies. It took hours before they were able to leave camp the next day.

Annie and her crew set out over the snow-covered glacier, but it was slow going. The men needed to stop frequently to rest, as their packs were heavy and the work was hard. They continued on until nightfall, still far away from the spot that Annie Smith Peck had hoped to reach in a single day. Once again, they camped.

On day four, Annie roped with Volkmar and Domingo carried on, but the other men fell behind as Cervantes was now suffering terribly from altitude sickness and had begun to spit up blood. Still, when they reached a steep slope, Volkmar cut steps into the ice until he was too tired to continue. Then Domingo took over the job. Finally they reached a somewhat level spot. The men were adamant that they stop and camp for the night. Nearly everyone was suffering the effects in various forms of altitude sickness.

The men began to grumble, saying that they no longer wanted to carry the bags. Some suggested climbing the rest of the mountain from where they were. Others offered the idea of heading right back down and being done with the whole affair. Annie Smith Peck was in her usual place—surrounded by men who were sick or scared or both and ready to give up on her mission.

But with repetition comes new ideas, so Annie tried a new approach with the crew this time:

Now was the time for diplomacy, and having had experience with mutinous crews in the past, I was able to manage better than before. I said nothing until they had rested, had supper, water, tea, some of my chocolate, and a moderate dose of aguardiente. They were evidently feeling better when I began my little speech, telling them how well they had done that day, but that it was impossible to reach the summit from there and return before night. Perhaps they might, as they could go faster than I, but I was the one who must do it. Now they were tired, so we would rest on the morrow, or move the camp just a little.

On Saturday, a good day’s work would bring us to a point from which on Sunday they could certainly gain the top. They need not go farther unless they wished. The essential thing was for me to attain the summit. If they enabled me to do this, they should each receive one pound bonus, besides the stipulated three soles a day. I promised further to give them some chicken and some chocolate and assured them of much glory if they really climbed this great mountain.

Annie’s speech worked. Carpio pledged his allegiance to the expedition, and the men followed suit. “We will go as far as you go,” said Julian, “even unto death.” Annie Smith Peck especially liked Julian, noting that he “was the most gallant of the men, often helping to pull off my boots at night; but usually no one offered assistance and I did almost entirely for myself besides tucking Mr. V. into his blankets.”

After a day of rest, they set out on Saturday, covering more ground than any day before. Happily, they made it around the left-hand peak and headed up the face of the mountain between the two peaks. Finally, around five p.m., they pitched the tent at the last camp. The men had pulled through after all—even though Cervantes was still coughing up blood. Annie was under her blankets two hours later, ready and excited for the day ahead.

On Sunday, July 16, everyone but Cervantes headed for the summit. They walked until they reached the upper part of a broad ridge, and then swung left to meet the one summit that everyone agreed was the highest. Annie Smith Peck took observations with the hypsometer. However, she would not be able to gain any information about the exact elevation of the town of Viraco, so there would be no way to measure the altitude of the mountain. Slyly, Annie figured that Bingham’s highly equipped party that was coming later would make an accurate triangulation, so there was no pressure for her to do so now. Instead, she just enjoyed the view, noting,

A splendid prospect we enjoyed, much finer than the one from Huascarán, though Coropuna itself was far less beautiful and imposing. In the clear sunshine from the blue and cloudless sky, the ocean was distinctly visible; nearer lay the desert to which abrupt ridges and narrow valleys lead down, one little green lake among the lofty hills. The Majes Valley seemed fairly straight. Elsewhere, dark cross ridges and peaks intercepted the nearer view below, except at the mountain’s foot, where the white houses of Machahuay, a village near Viraco, and fields of green, brown and gold afforded a pleasing variety. To the south and east were a splendid panorama of mountains.

The Coast Range, besides many lower elevations, presented a number of fine, snow-clad peaks: the volcano Misti, above Arequipa, with its neighbors Pichu-Pichu and Chachani, all better covered than I had ever seen them before. Nearer were several other mountains bearing much greater snowfields; one no doubt was Antasara, another whose name I was unable to learn, both appearing as lofty as our own position. Of even more interest was the view to the north or rear regarded from the face which we had ascended. Here were several other peaks, one of which, called the Toro, situated on the side toward Chuquibamba, appeared of greater elevation.

The next day, they headed back to Viraco, where they were greeted by the governor, the lieutenant, and about ten other men who had been sent out to search for Annie and her crew. When, a few days before, men reported back from the snow line that they were unable to see Annie Smith Peck and her crew, the prefect of Arequipa began a search for them.

Now the search that had begun was ended and everyone enjoyed celebrating their success on the mountain.

HANNAH KIMBERLEY is an academic who has made Annie Smith Peck the focus of her scholarship, resulting in her book A Woman’s Place Is at the Top. She is considered the authority on Peck and her work is referenced for numerous publications such as American National Biography and National Geographic, anthologies on women explorers and works of history such as A World of Her Own: 24 Amazing Women Explorers and Adventurers, and publications by the Rhode Island Historical Society.