By Ginger Adams Otis

Black Firefighters

It’s no secret that FDNY firefighters are among the best in the world, but here’s a little-known fact about New York’s Bravest: a black woman was among the city’s earliest black firefighters. Her name was Molly Williams, and she was a slave.

Not much detail exists about Williams beyond a few bare facts: she belonged to the family of a wealthy merchant named Benjamin Aymar. He earned a pretty crust as a principal in Aymar & Co., the family business, and maintained an opulent residence at 42 Greenwich St., where Williams also lived – likely tending to his eight children.

Industrious and able-bodied, Aymar was also a volunteer in the city’s fledgling firefighting corps –a prestigious but slightly rough-hewn cadre of men who stood ready to fight the red devil day or night. In most cases, the men who volunteered were those who had the most to lose. Merchants like Aymar could be wiped out by even one errant spark — if it flamed out of control among the warehouses along Lower Manhattan’s docks. For most of Aymar’s early life, New York City still bore the scars of great fires of the past.

Whatever Aymar’s motivations were, he didn’t give up his luxury lifestyle when he worked his unpaid shifts– and to make sure he was properly tended to, he brought along his slave Molly Williams.

Together, the duo would check in at Aymar’s firehouse, Oceanus Engine Co. 11, in Lower Manhattan, not far from where Zuccotti Park is today. While he hob-knobbed with his fellow red-shirted vollies, Williams cooked and cleaned for the crew, keeping everything tidy and clean – including its heavy, hand-pulled water pumper.

She was around the firehouse enough to learn how to use the machine, which had to be hauled by dragropes by several strong men when full of water. The word the firehouse was that Williams was as “as good a fire laddie as many of the boys,” and in 1818, amid a devastating winter blizzard she got her chance to prove it.

According to lore, Williams was in the firehouse with Aymar, doing her usual chores and tasks — as well as taking care of most of the men of Oceanus 11, who’d been stricken by a virulent flu. As she rushed to and fro, the alarm bell sounded. There was a fire, and she was the only one well enough to go.

The sturdy slave – in her checked apron and calico dress — hauled out the pumper with as much strength and speed as any man and answered the call to duty. She acquitted herself so well, so the story goes, that the men of Oceanus 11 declared her an unofficial member of their team. Williams became “Volunteer No. 11.”

No official records of blacks serving in among the city volunteer forces exist, but some anecdotal accounts remain. Charles Dickens, during one of his two trips to America in the mid-1800s, wrote of seeing a group of merry firefighters tromping through a snowstorm in New York City. In their midst, a smiling black man who sang along with them with great glee, a woolen red muffler wrapped round his neck.

By the 1900’s – 35 years after the volunteer forces had been replaced by paid professionals, the modern-day FDNY – there were several blacks working for the Fire Department, but only one was actually a black firefighter.

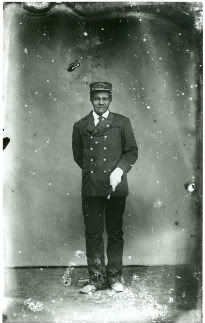

Along with a black oil combustibles clerk and a black fire inspector, there was William H. Nicholson – a Virginia-born black man whose appointment to the FDNY is shrouded in mystery. He popped up among Brooklyn smokeaters in 1898 – the same year the borough was annexed into New York City. Overnight, Nicholson became a member of the all-white FDNY.

Unprepared to deal with him, the rank-and-filed convinced headquarters that Nicholson would be better off serving the public as a caretaker to sick FDNY horses than living round-the-clock in a firehouse and fighting big blazes. For the rest of his career, Nicholson stayed out of sight in the stables — emerging once a year on July 4, when the department demanded all hands on deck.

Nicholson didn’t get a storybook career –but few pioneers ever do. It fell to the next wave of black firefighters to break into the firehouses, and from there grow their numbers incrementally over the years – and not without some challenges of their own.

In terms of official recognition, there’s a blank slate when it comes to black contributions to New York’s firefighting forces before the turn of the 20th century – little is written and even less is known. But as the example of Molly Williams shows us, much remains to be found.

GINGER ADAMS OTIS is the author of Firefight: The Century-Long Battle to Integrate New York’s Bravest has been writing about New York City and local politics for more than a decade. She is a staff writer at the NY Daily News and previously worked at the NY Post. Otis started covering City Hall and the Fire Department when she worked for The Chief-Leader. She’s been a radio and print freelancer for WNYC, the Associated Press, BBC, National Public Radio, The Village Voice and national magazines such as Jane and Ms. She lives in Harlem, NY.