by Brad Ricca

Grace Humiston was a celebrated lawyer, a famous detective, and the first female U.S. District Attorney in history. Her specialty was tracking down missing persons, yet she remains largely (and mysteriously) missing from history herself.

The True Story of New York City’s Greatest Female Detective and the 1917 Missing Girl Case That Captivated a Nation

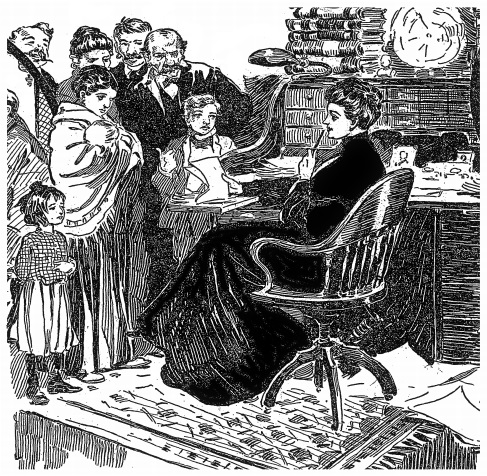

After graduating from N.Y.U. Law School in 1903, Grace Humiston passed the bar and opened a legal clinic for low-income clients, often immigrants and children. Her cases ranged from deportation disputes to stolen Spanish jewels. When men looking for work began disappearing from her neighborhoods, Grace Humiston tracked them down to the deep south. There, often wearing a disguise, she found secret forced labor camps that used a practice of debt slavery called peonage to produce turpentine and cotton. For this work in the swamps and fields, Grace Humiston was appointed a U.S. district attorney under President Teddy Roosevelt. She testified before Congress, dealt with ill-behaved husbands, traveled the world, and settled in New York City where she tried to single-handedly solve the country’s problems. She seemed to be a very powerful middle-aged woman, known throughout the country and in possession of substantial political capital. How then did she disappear so completely? It is hard to think of her story, especially given the events of the past electoral year, without a sense of déjà vu.

Grace Humiston’s most Famous Case

Grace Humiston’s most famous case was that of 18-year-old Ruth Cruger in 1917. After Ruth disappeared running errands in Harlem the day before Valentine’s Day, the police conducted an investigation that swiftly came up empty. The cops shook their heads and declared that Ruth, who taught Sunday School and had no boyfriend, had somehow eloped to an unknown destination. This conclusion made Ruth’s father furious, so he hired Grace to find his dear daughter. Rumors swirled in the newspapers of mysterious affairs and even white slavery. But after reviewing the case, Grace insisted that Ruth was not a “bad girl” and focused on a single suspect, a motorcycle shop owner named Alfredo Cocchi who had sharpened Ruth’s ice skates the day she went missing. The police had searched his store, questioned him, and cleared him of any involvement in Ruth’s disappearance – twice. But Grace had a nagging hunch.

With Julius J. Kron, her hard-boiled, right-hand detective by her side, Grace Humiston, who always wore black, unraveled an uncanny mystery that wound its way from a secret door hidden in the earth all the way to a crumbling tower in Italy. After Grace Humiston solved the case – after an almost-unbelievable set of circumstances, deduction, and sheer luck – the police gave her a title and badge as an official consulting detective to the NYPD.

But Grace Humiston’s great victory came at a price. A massive inquiry was launched into wrongdoing in the Cruger case, leaving many cops with a grudge against the woman in black. The scandalous findings of the investigation suggested actual police involvement in the crime itself. As officers were dismissed from their posts, Grace moved on to other high-profile, national cases, including the investigation of a young wife’s death in Annapolis and the black man charged with her murder. John Snowden, the accused, was convicted after an afternoon alone with police in a closed room. He emerged bruised and bloodied. When Grace heard this, she vowed to save his life from the gallows yard.

Grace Investigates a Case on Long Island

Finally, Grace Humiston took on the U.S. Army in her final – and most problematic – major detective case. Hearing whispers of sex trafficking and unwanted children being stowed away near the new Camp Upton on Long Island, Grace began snooping around. But when she sprung her trap, she was accused of planting information. The press savagely turned on her, leaving her scrambling, for the first time in her life, without hard evidence. Had the indomitable sleuth truly fallen so far or was this, as Grace claimed, a clandestine plot against her? She had enemies, to be sure, as her many successes had made many men feel somehow shamed. There was one such man who disliked Grace who would go on to become one of the most powerful men of the twentieth century. A month after the Upton affair, Grace would be the target of an assassin.

By all accounts, Grace Humiston’s work – in the courtroom, on the tenement stoops, in the swamps, and even across the world – marked her as a social crusader of the first order. The remarkable thing is that the person herself remains strangely elusive, hinting at a bigger, or perhaps more human, mystery.

The one constant to Grace Humiston’s story is the undeniable space in the middle indicative of all unsolved crimes. Whether that unknown element was Ruth Cruger, her other cases, or even Grace herself – the police, the media, families, the church, and others – were all trying to fill it with answers. Some of them were right ones; some were very wrong. Like the girls she searched so tirelessly for, Grace herself is somewhat of a lost person. When I stumbled across her story in a 1917 edition of the New York World, I was shocked to find only a few things written about her. Even more frustrating, there were no personal diaries, no boxes full of correspondence, not even a small family collection in a quaint Northeastern library. And for someone who was such a feared lawyer, Grace Humiston didn’t even leave a will.

The True Story of New York City’s Greatest Female Detective and the 1917 Missing Girl Case That Captivated a Nation

I eventually found clues in newspapers, court records, magazines, and even rumors whispered over telephones. Grace Humiston’s story, like any good mystery, is then best understood as a collective of evidence, stretched out across time. Only when it is spread out before us can we put the evidence together to first question it, then to build a composite sketch of the woman the press named “Mrs. Sherlock Holmes.”

And like all significant crimes of violence or omission, this one stretches back into the past to color every experience that came before it. These are the type of crimes that somehow move back and forth through history itself, only occasionally stopping to reveal clues like the one I found while writing the last page of the book – that made me want to scream.

BRAD RICCA is the author of Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster–the Creators of Superman, winner of the Ohioana Book Award for Nonfiction and the Cleveland Arts Prize for Literature. His first book of poetry, American Mastodon, won the St. Lawrence Book Award. His documentary Last Son won a Silver Ace Award at the Las Vegas International Film Festival. He has been a contributing expert for the New York Daily News, The Wall Street Journal, the BBC, the AV Club, and All Things Considered. He is a SAGES Fellow at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, where he was born and now lives with his family.