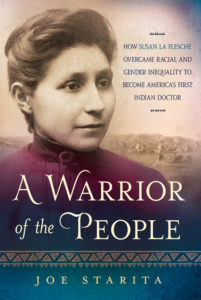

by Joe Starita

Born about 1818 in northeast Nebraska, the son of a French fur trader and an Indian mother, Joseph LaFlesche grew up among a new subgroup of mixed-blood children—children who emerged from the bustling trading post culture clustered along the region’s rivers, especially the Missouri.

As the nineteenth century unfolded, as more and more outside pressures threatened their shrinking world. The Indians needed weapons. Guns, to ward off the threats and to hunt the very animals whose furs could be bartered for those guns. So the fur-trading posts became key centers of commerce linking the white and Indian worlds, as well as white fur traders and Indian women. Over time, their mixed-blood offspring, often with French surnames, began to populate the trading posts and eventually integrate themselves into business ventures, tribal affairs, and occasionally leadership positions within the tribes.

Even by mixed-blood standards, the young Joseph LaFlesche lived a complex life. They bounced from one Indian village to another. Observing different tribal traditions and customs, absorbing different cultures and languages. By an early age, he spoke Pawnee, Dakota, Otoe, Ioway, Omaha, and French. He also spent a good deal of time hunting and traveling with his French fur trader father. Including several long trips down the Missouri to St. Louis, all of which afforded him a worldview uncommon to many others in that area, in that era. He paid close attention to the two different worlds. And he saw many things he would long remember.

Joseph LaFlesche Settles with the Omaha

Eventually, Joseph LaFlesche settled down and settled in with his Omaha relatives, and as a young man he took a job working at one of Peter Sarpy’s thriving trading posts just south of Omaha. At the height of the fur trade, these posts teemed with all manner of activity and characters. It was here, in the spring of 1833, that the post’s workers could have encountered the German explorer Maximilian, Prince of Wied, and his Swiss artist companion, Karl Bodmer, who had embarked on a twenty-five-hundred-mile trek by steam and keel-boat up the Missouri to observe, study, and document—with journals and paintings—the colorful American Indians of the Upper Missouri.

And it was also at Sarpy’s trading post where Joseph LaFlesche met Mary Gale, an engaging mixed-blood daughter of an energetic, strong-willed Ioway Indian and a U.S. Army surgeon, one of the first white doctors west of the Mississippi. Several years after her doctor husband died, Mary’s mother married Sarpy, so Mary ended up spending much of her childhood at the trading post where Joseph LaFlesche worked.

Observing the Omaha

A number of years before meeting his wife, Joseph LaFlesche had begun to closely observe the customs of the Omaha. Absorbing the age-old traditions, to carefully study the ancient rites and rituals. He also had made a conscious habit of cultivating friendships among the Omaha elders. Listening intently to their accounts of traditional ceremonies, of trying to understand exactly how the fabric of Omaha culture knit together. Understanding what it might take to alter, to rearrange, some of the patterns of the tribe’s cultural quilt.

During all of his visits to the other tribes, throughout the long riverboat journeys to St. Louis with his father, in all he had seen and heard around the trading posts, Joseph had come to an increasingly unshakable conclusion. Soon, the overwhelming power and presence of the white man would suffocate his people, kill the old way of life once and for all. So if their people were to survive, a new one must be forged from the scrap heap of buffalo bones, land loss, ambitious settlers, Sioux war parties, devastating disease, and the white man’s whiskey. Something must occur. A fundamental shift in cultural values, for the Upstream People to overcome the powerful sense of doom and hopelessness that had begun to settle in and spread through village life.

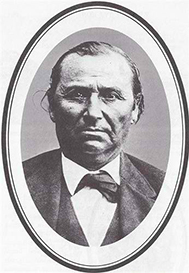

Big Elk and Joseph La Flesche Become Close

In 1846, Joseph LaFlesche and Mary Gale became husband and wife. By then, Joseph’s stock—his thoughtfulness, strength, and respectful commitment to learning tribal culture from the elders—had risen a great deal within the Omaha village, nowhere more so than with the one who mattered most.

Big Elk had taken a liking to Joseph. He trusted him, believed that the younger man had a vision aligned with his own and understood that the flood would sweep them all away if they didn’t compromise, if they didn’t begin to assimilate. So the powerful, respected chief of the Omaha increasingly took him under his wing and began to signal to others that Joseph would one day succeed him. Although the old chief already had a son, who, based on long-standing Omaha tradition, should succeed his father, the boy was young and sickly.

While the boy was still alive, Big Elk adopted Joseph, suggesting in word and deed that it would be Joseph who succeeded him as the Omaha’s new chief. About two years after the wedding of Joseph and Mary, Big Elk performed a traditional Pipe Dance Ceremony honoring Mary. Shortly after, a public crier proclaimed to the village that Joseph was now the chief’s eldest son and would succeed him. Not long after, Big Elk arranged to have Joseph placed in his own kinship clan—not his mother’s, which was the age-old custom. So step by step, the old chief methodically arranged passage for the younger man to succeed him, to carry out his vision. That younger man, according to the Omaha’s 1848 tribal census, was now officially listed as E-sta-mah-za—Iron Eye.

Read more about the Indian Wars and the Battle of Rosebud Creek here

Big Elk is Taken Ill

One afternoon in 1853, while the people were having a feast, Big Elk went out hunting and killed a deer. A few hours later, he came down with a fever. Big Elk sent for Iron Eye. “My son,” Big Elk said, “give me some medicine.” Iron Eye sent a runner to Bellevue for medicine, but it was a three-day journey, too long for the gravely ill chief. Feeling the end was near, the old chief again called for Iron Eye. “My son, I give you all my papers from Washington, and I make you head chief,” he told the younger man. “You will occupy my place.” Shortly after the old man chief died, E-sta-mah-za became one of the Omaha Tribe’s two principal chiefs.

From that time on, the last recognized chief of the Upstream People struggled for much of his adult life with the central issues that had first brought him into Big Elk’s fold:

How could he, their new chief, find the right balance between who they were then and who they had always been. Who they must now become? How could they become white enough to survive in the new world order? But red enough to retain a cultural identity, a strong sense of who the Omaha were? Could they learn to walk the red and white roads simultaneously?

For many years, there was much he had come to admire about white culture. He was not shy about proclaiming it as the new chief of the tribe.

Joseph LaFlesche Becomes Chief of the Omaha

“The white man looks into the future and sees what is good,” he told his people. “That is what the Indian is doing. He looks into the future and sees his only chance is to become as the white man.”

That sentiment was not shared by everyone in the tribe, and it eventually led to a bitter division within the Omaha, a conflict over accepting new ways or embracing old ones, a split that pitted the more liberal “Young Men’s Party” against the older conservatives.

But not long after becoming chief, Joseph LaFlesche wasted little time in leading by example—in showing the tribe the path he believed would lead to the survival of the Omaha, the same one he and Big Elk had often discussed.

In short order, he and members of the Young Men’s Party cut hundreds of logs and hauled them to a sawmill. Then their chief hired white carpenters to build him a large, two-story wood-frame house, thought to be the first Indian wood-frame house west of the Missouri. The others in his camp soon followed suit, building smaller wood homes for their families. Next, Joseph LaFlesche began laying out roads, fencing a one-hundred-acre tract, and dividing it into smaller shares so that each man in the village could have his own plot to farm.

Later, he took a similar approach with his children. He and Mary had four daughters, and Joseph later had three more children with another wife. He saw his children, and all Omaha children, as the tribe’s future, and he strongly believed their future was at risk if they remained shackled to the past.

Rejecting some of the Omaha Traditions

So Joseph LaFlesche forbade his sons to have their ears pierced. His daughters to participate in the traditional Mark of Honor Ceremony. Among the Omaha, it was customary for fathers who had achieved a certain status for hunting prowess or peacemaking skills to place the mark of honor on their daughters. The mark reflected the father’s accomplishments and signified that the girl was the daughter of a chief or of someone of high social standing within the tribe. The mark often consisted of a sunspot image tattooed on the forehead and a four-pointed star on the throat, the points representing the life-giving winds from each of the four directions. Often, the Mark of Honor Ceremony occurred around noon. When the sun was at its highest point in the sky. But Joseph LaFlesche wanted no such markings, no tattoos of any kind, for his children.

“I was always sure,” the chief would later explain, “that my sons and daughters would live to see the time when they would have to mingle with the white people, and I am determined that they should not have any mark put upon them that might be detrimental in their future surroundings.”

Yet he was equally insistent that all of his children know all of the Omaha’s traditional ceremonies, songs, beliefs, values, and customs. That they all spoke the Omaha language and maintained the cultural glue that kept their Indian identity intact.

Maintaining Identity Combined with Education

Decade after decade, LaFlesche struggled to keep threading an elusive bi-cultural needle, one that he believed would ensure the success of his children, the survival of his people. And year in and year out, he continually stressed to his children that there was one key value they must all adopt from the white man: education.

Education, he preached, was the key. It could help save their people. It’s what could unlock the American Dream.

Education is what we can do to help ourselves—to better ourselves.

Over time, Joseph LaFlesche’s eldest daughter would become one of America’s earliest, most prominent Indian civil rights leaders. His son, the nation’s first Indian ethnographer. Another daughter became a teacher. And there was his youngest daughter, Susan. As a small child, she had witnessed the death of one of her people and the indifference of the white doctor to her death. It was something she would never forget.

JOE STARITA was the New York Bureau Chief for Knight-Ridder newspapers and a veteran investigative reporter for the Miami Herald. His stories have won more than three dozen awards, one of which was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for local reporting. For the last twelve years, he has held an endowed professorship at the University of Nebraska’s College of Journalism. The Dull Knifes of Pine Ridge won the MPIBA Award and received a second Pulitzer nomination.