by James A. Colaiaco

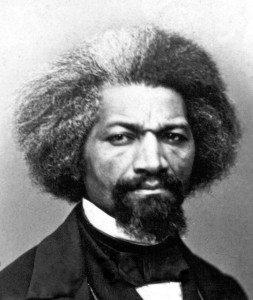

Frederick Douglass

On Monday, July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass, the former slave, made his way to majestic Corinthian Hall, located in downtown Rochester, New York, near the Genesee River. He had been invited to deliver a speech to celebrate the Fourth of July. For the past few weeks, he had labored into the night, gathering his thoughts about the urgent message he wanted to give the nation. Arriving at Corinthian Hall, Douglass, the keynote speaker of the day, walked to his seat and faced his audience. With great dignity and a stern countenance, he surveyed the assemblage of mostly white people.

Image is in the public domain via WikiMedia.com

Since the early years of the American republic, the Fourth of July has been the day Americans reaffirm their common identity and purpose in a collective ritual. For Douglass, the day had multiple meanings. It was the anniversary of the birth of the United States of America, which, he agreed, should be celebrated; the Fourth of July was the anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the historic document that committed the nation to the ideals of liberty and equal rights for all. But for Douglass, the Fourth of July was also a day to remember that America’s ideals remained unfulfilled for blacks enslaved in the South. Throughout his life, Frederick Douglass struggled to resolve the American dilemma, the contradiction between the ideals professed by the nation’s Founders and the practice of denying human rights to black Americans and other minorities.

A self-educated fugitive slave, abolitionist, advocate for women’s rights, orator, journalist, and diplomat, Frederick Douglass was the most famous black person of the nineteenth century. He is best known for his three inspiring autobiographies. But his greatest legacy to America is his oratory, forged in the crucible of the battle against slavery in the years prior to the Civil War. With extraordinary courage, he had escaped from his slave master. Having taught himself to read and write while a slave, Douglass is one of the most inspiring examples of the power of literacy. Shortly after attaining his freedom, he came under the influence of the great abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, who stirred the nation’s conscience by calling for the immediate and complete abolition of slavery. As a member of Garrison’s Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass honed his oratorical skills. After publishing his first autobiography in 1845, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, which emphasized the moral evil of slavery, Douglass made the first of two excursions to Great Britain, where he spoke from a variety of platforms, electrifying his audiences. While he initially subscribed to Garrison’s rigid views, including denouncing the United States Constitution as pro-slavery, Douglass’s careful study led him to embrace the document as the abolitionists’ greatest legal weapon.

Having taken his anti-slavery message to Britain in 1847, Frederick Douglass had achieved international recognition as a great orator. He emerged as an independent thinker, ready to create his own path. In 1847, as an offensive against slavery, he founded an abolitionist newspaper, the North Star, in Rochester, New York. To the dismay of the Garrisonians, by 1851 he had converted not only to the United States Constitution,

but also to pragmatic party politics. During the next decade, as tensions over slavery between the North and the South pushed the nation to the brink of civil war, Douglass delivered hundreds of speeches throughout the North calling upon the federal government to abolish slavery in the South. Douglass warned that failing to eradicate the moral evil of slavery would arouse divine retribution.

Despite the valiant efforts of Douglass and others, slavery continued to spread. The antebellum period was dominated by a struggle between the North and the South over whether newly acquired lands would become slave or free states. The outcome would have important political consequences, including control of Congress, the office of the presidency, the composition of the Supreme Court, and ultimately the fate of the nation. In 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law, which in effect nationalized slavery by requiring citizens in the North to assist in the return of runaway slaves. Douglass began advocating the abolition of slavery through political means, including support for anti-slavery political parties. When many black reformers, along with anti-slavery whites, believed that the best solution was to free the slaves and ship them out of the United States, Douglass remained a committed integrationist, insisting that blacks should not abandon America and its ideals. He also practiced civil disobedience as a leader in the Underground Railroad movement that assisted hundreds of fugitive slaves in their escape from the South to safe haven in Canada.

“Time and events have summoned me to stand forth both as a witness

and an advocate for a people long dumb, not allowed to speak for

themselves, yet much misunderstood and deeply wronged.”

—Frederick Douglass,

In the 1850s, Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln—two giants on the stage of American history—embarked on paths that would converge on the issue of slavery. On June 16, 1858, Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech proclaimed that the nation could not survive half slave and half free. While both Douglass and Lincoln, inspired by the ideals of liberty and equality enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, agreed that slavery was immoral, they disagreed on the best method to abolish the institution. Frederick Douglass had become convinced that the Constitution was anti-slavery, but Lincoln insisted that the document did not authorize Congress to abolish the institution in the South. The most that the federal government could do, in Lincoln’s judgment, was to prevent slavery’s extension into new territories. Lincoln hoped that, confined to the South, slavery would die a natural death. While Lincoln was convinced that preserving the Union was more important than abolishing slavery, Douglass believed that a Union with slavery was an unacceptable betrayal of the nation’s democratic ideals.

Read more about African-American history and New York’s first black firefighters here

In the years prior to the Civil War, Douglass emerged as a formidable interpreter of the nation’s founding documents. Read from an ethical perspective, he argued, the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were essentially abolition documents. The Preamble to the Constitution alone provided sufficient legal basis to eradicate slavery. The Constitution was designed to secure for all persons the inalienable natural rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness proclaimed in the Declaration. The Supreme Court of the United States disagreed. Five years after Douglass’s July Fourth oration, in the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, speaking for a pro-slavery Court, ruled that no black American, slave or free, was a citizen of the United States. Taney argued that according to the Constitution blacks were property, not human beings. They were not endowed with inalienable rights. The Chief Justice defended the Court’s decision on the grounds that it expressed the original intentions of the nation’s Founders. Dred Scott essentially denied the American dilemma and was a devastating blow to the anti-slavery movement. In the minds of many Americans, the Supreme Court had definitively settled the slavery question that had plagued the nation since its inception. Black Americans were unequivocally excluded from the rights of the Declaration of Independence. Nor were they among “We the people” who established the Constitution. Blacks were not citizens of the United States, but aliens. If they were not included within the body politic in the first place, the nation could not logically be accused of violating its founding principles.

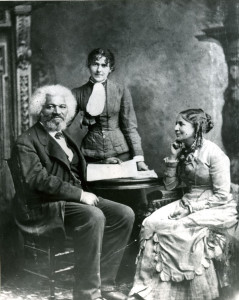

Image is in the public domain via WikiMedia.com

Dred Scott aroused a storm of protest throughout the North, edging the nation closer to civil war. The decision radicalized Douglass. He challenged the Supreme Court, arguing that the decision was based upon a misreading of the United States Constitution. But the prospect of repealing Dred Scott was bleak. As the battle against slavery by means of moral persuasion and politics proved to be ineffective, Douglass reluctantly concluded that war against the South was inevitable. He had always rejected violence in the past, but Dred Scott made him seriously consider the idea of a slave rebellion in the South. When in 1859 the white abolitionist John Brown sought Douglass’s support for his raid on Harpers Ferry, he rejected the venture only because it was strategically unsound and not because it would be violent. Soon after Brown’s raid was crushed, making Brown a martyr for the abolitionist cause, Douglass left for Britain, once again bringing the debate over human rights to an international forum.

Late in life, in his third and final autobiography, composed at his home in the Anacostia estate of Cedar Hill, Washington, D.C., Douglass reflected upon the issue that consumed him: “I write freely of myself, not from choice, but because I have, by my cause, been morally forced into thus writing. Time and events have summoned me to stand forth both as a witness and an advocate for a people long dumb, not al- lowed to speak for themselves, yet much misunderstood and deeply wronged.”4 The same motive drove his oratory. He spoke at antislavery meetings, state black conventions, and ceremonial gatherings. He spoke in halls, churches, auditoriums, courthouses, tents, and open fields. He spoke to give voice to black Americans so that they might be freed from the inhumanity of slavery and from the injustice of racial segregation. He spoke so that blacks might be inspired to stand up for their human rights to liberty and equality.

America took notice. The New York Tribune and the Chicago Tribune printed full-length accounts of Douglass’s many speeches, and they were summarized in the New York Times.5 As early as 1841, one paper observed: “As a speaker [Douglass] has few equals. It is not declamation— but oratory, power of debate. He has wit, arguments, sarcasm, pathos—all that first rate men show in their master efforts.”6 In 1859, the New York Tribune included Douglass among the two hundred people of the nation’s “Lecturing Fraternity,” recognized for their exceptional rhetorical ability. In 1872, the New York Times called him “the representative orator of the colored race.”7 The abolition movement had no more inspiring advocate than Douglass. “White men and black men,” proclaimed black abolitionist William Wells Brown, “had talked against slavery, but none had ever spoken like Frederick Douglass.”8 In an age when the standards of oratory were much higher than today, many of Douglass’s speeches, delivered over a period of more than fifty years, were considered among the best in the American rhetorical tradition.

Two weeks prior to Douglass’s July Fourth 1852 address, black orator William G. Allen singled out his fellow abolitionist’s unique gifts: “In versatility of oratorical power, I know of no one who can begin to approach the celebrity of Frederick Douglass.”9 Douglass’s reputation as a speaker continued unabated throughout the nineteenth century. In 1893, two years before Douglass’s death, James Monroe Gregory, professor of classics at Howard University, offered these words of praise: “By whatever standard judged, Mr. Douglass will take high rank as orator and writer.” A great orator like Douglass is one who not only delivers great speeches, but also “touches the hearts of his hearers.”10 When Douglass died on February 20, 1895, the reformer Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who knew him since the 1840s and with whom he made common cause supporting women’s rights, paid him eloquent tribute in her diary. Stanton never forgot the first time she saw Douglass speak: “He stood there like an African prince, majestic in his wrath. Around him sat the great antislavery orators of the day, earnestly watching the effect of his eloquence on that immense audience, that laughed and wept by turns, completely carried away by the wondrous gifts of his pathos and humor. On this occasion, all the other speakers seemed tame after Frederick Douglass.”

Frederick Douglass awakened the conscience of the nation, compelling Americans to confront the gravest moral dilemma in its history. His attack on slavery and defense of human dignity brought him into conflict with the slave states of the South and with the states of the North, where free blacks were segregated and deprived of the full benefits of citizenship. He confronted a nation reluctant to take the necessary steps to abolish slavery. Despite formidable obstacles, he refused to be silenced. Delivering hundreds of speeches on behalf of those condemned to live in slavery, Douglass inspired, converted, and provoked. He mesmerized his audiences. No speaker was more impassioned, more devoted to the advancement of human rights. No person understood better the meaning of the American creed as embodied in the Declaration of Independence and the Preamble to the United States Constitution, and no one was more eloquent in summoning the nation to fulfill this creed for all, regardless of race.

James A. Colaiaco received his Ph.D. in intellectual history from Columbia, and has for the past twenty-five years taught Great Books at New York University in the General Studies Program at NYU. Colaiaco is author of FREDERICK DOUGLASS AND THE FOURTH OF JULY.