by Jack Kelly

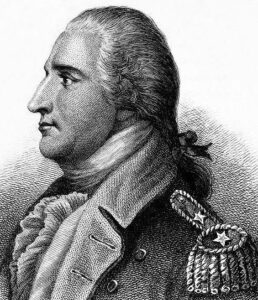

It was said about Benedict Arnold that he never did anything by halves. Was he a traitor? Yes. But not just any traitor. He was the renegade of all renegades, the man whose name became a synonym for treason, the Judas Iscariot of American history.

A closer look reveals a complex character beyond the treason. Arnold was one of the most important and effective officers to lead patriot troops in the Revolutionary War. He secured the Americans’ defenses in the north in 1775, fought off a British invasion in 1776, and led the fight at the turning-point Battle of Saratoga in 1777. His lower leg was shattered by an enemy bullet in that chaotic brawl.

Following a period of inaction and brooding, Arnold defected to the British in 1780. He tried to hand over the important post at West Point and later led British soldiers against Americans. His betrayal was crushing news at a time when the patriots’ hopes were at a low ebb.

After the Revolution, Arnold’s change of heart continued to confound Americans. As historian Gardner Allen wrote in 1913, it was “by a singular instance of the irony of fate, that we owe the salvation of our country at a critical juncture to one of the blackest traitors in history.”

Arnold’s treachery raised two important issues that are still relevant today. One was the need to recognize that humans can be and often are paradoxical. The other was that trust is essential to public concord. That these two notions are themselves contradictory only shows the difficult balancing act of citizenship.

Arnold presents the epitome of paradox: a genuine American hero who was also the nation’s worst villain. He helped launch a revolution—he tried his best to destroy that same revolution.

Nobody likes a paradox. Early biographers tried to erase the conflict by downplaying Arnold’s achievements in the war, however well documented, or by asserting that his motives and character were rooted in villainy. In recent years, the record has been clarified, but distortions of Arnold’s early triumphs remain.

It’s important to understand, as Shakespeare wrote, “That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain.” Complex figures have been common in our history—Aaron Burr, John Brown, Huey Long. Even Thomas Jefferson, an enslaver who sang the hymns of freedom, has come to be seen for his contradictory impulses.

We have to be ever alert for the paradoxical figure: the demagogue, the foreign agent, the confidence man, the traitor disguised as a patriot, the articulate incompetent who talks but does not know, the destroyer who thinks he’s creating.

George Washington’s first reaction on learning of Arnold’s betrayal was, “Who can we trust now?” One reason Arnold’s treason shocked patriotic citizens was that Americans were trying to construct a republic. Such a venture had never been attempted on such a scale or among such a diverse population. What it required, patriots thought, was trust.

“We mutually pledge to each other,” the signers of the Declarations of Independence vowed, “our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” To each other—personal trust laid the foundation for self-government.

Could the people trust the delegates they sent to Congress? Could Congress trust the men of the Continental Army? Could the soldiers trust the citizens to support them? These were the questions raised in the founding era—and repeated throughout our history. Trust in the American political system has weathered many challenges—world wars, economic panics, intense political strife, even a civil war that killed six hundred thousand citizens.

Today we are faced with our own challenges. We are being asked to understand the motives and dynamics of complex public figures, to judge their actions, to recognize corruption, to guard against treason. At the same time, we have a pressing need to trust our fellow citizens across a growing and rancorous divide.

These are the responsibilities that keep us awake at night and that send us back to history for instruction. The past holds no guiding light to show us the way ahead. But a clear view of history gives us a critically important perspective. The paradoxical image of Benedict Arnold—genuine hero, utter traitor—stares at us from the rearview mirror as we go speeding into our perilous future.

Originally published on Jack Kelly’s Talking to America.

Jack Kelly is a journalist, novelist, and historian, whose books include Band of Giants, which received the DAR’s History Award Medal. He has contributed to national periodicals including The Wall Street Journal and is a New York Foundation for the Arts fellow. He has appeared on The History Channel and been interviewed on National Public Radio. He grew up in a town in the canal corridor adjacent to Palmyra, Joseph Smith’s home. He lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.