by Susan Ronald

In the following excerpt from The Ambassador, acclaimed biographer Susan Ronald discusses the early life of Joseph Kennedy, foreshadowing his controversial stint as US Ambassador to Great Britain on the eve of World War II.

(Photo by Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

Joseph Patrick Kennedy was sworn in as U.S. Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s in London on February 18, 1938. His appointment was the belated reward for backing President Franklin D. Roosevelt in his successful reelection campaign of 1936. As thanks for his efforts in the 1932 election, Kennedy became the first ever Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) from June 30, 1934, to September 23, 1935, and the first Chairman of the Federal Maritime Commission from April 14, 1937, to February 19, 1938.

Then, as now, America’s ambassadors were an uneven mix of high net worth individuals—like Kennedy—and career diplomats. Often they were at loggerheads with one another, but the State Department pay scale for ambassadors was meager. Having ambassadors who could entertain lavishly in places like London, Paris, and Rome was deemed to be worth the potential friction. Since Kennedy did not have the skill set of a career diplomat, his legacy would depend entirely on what he made of his time in office during one of the most difficult periods in world history.

So, who was Joe Kennedy?

A second-generation American of Irish descent, Joe was born on September 6, 1888, in the predominantly immigrant quarter of East Boston, or Noddle’s Island, as it was then known. Kennedy grew up cocky, confident, and devoutly Catholic. He would always claim that his father, Patrick Joseph “P.J.” Kennedy, had been excluded from politics because he was an Irish Catholic. Yet Kennedy’s Irish Catholic father-in-law, the Democrat John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, had served in the Massachusetts state senate and in the U.S. House of Representatives, and was twice the city’s beloved mayor.

In truth, P. J. Kennedy was a saloonkeeper of considerable influence, who preferred the “I scratch your back, you scratch mine” machinations of behind-the-scenes ward politics, like Frank Skeffington, the Edwin O’Connor character in the 1956 bestseller The Last Hurrah. Local politics promoted respect in the community—even if the methods employed by the neighborhood bosses were often illegal. Daily, P.J. and men like him doled out heaps of food for the starving, treats for orphans, whisky for a dying man, and much more. Ward bosses were the trusted shadow government, and often the only men who helped the immigrant poor, all in exchange for their votes. Poverty-stricken young men of intellectual promise were saved by politics, and men like P.J. and Honey Fitz were prime examples. Back then, local politics preferred street wisdom to a college degree.

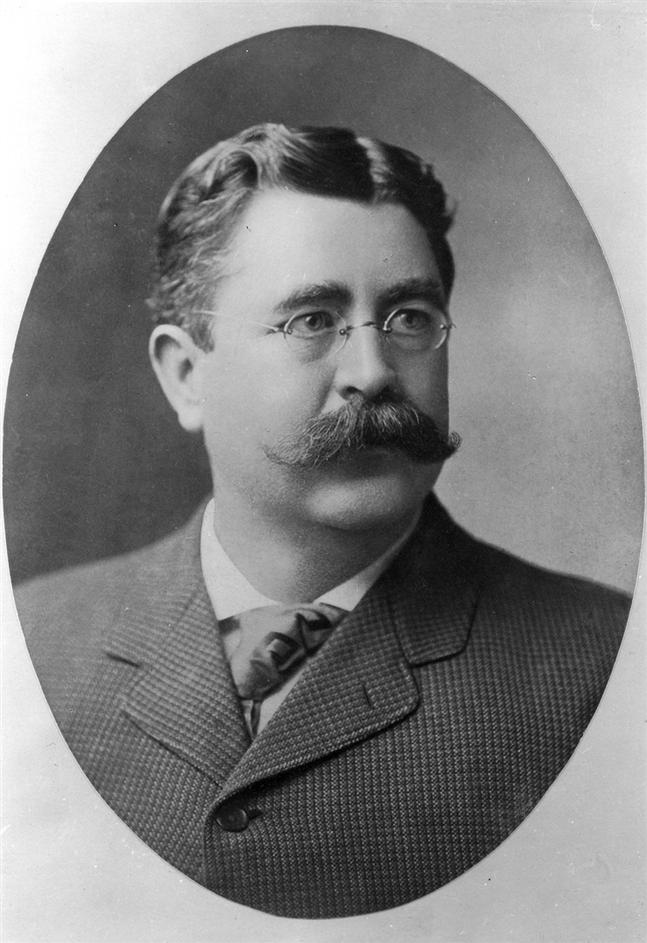

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

P.J. was expert at getting rich off his own largesse. As the boss of East Boston’s Ward Two, he passed his philosophy of life on to Joe: nothing is given to you on a plate; you have to give a little to get a lot. P.J.’s Ward Two political endeavors raised him to the middle class; which, in turn, enabled him to pay for Joe to receive his education at the expensive and prestigious—albeit Protestant—Boston Latin School and Harvard University. Joe’s grades in these institutions were, at best, mediocre.

At Harvard, social acceptance outweighed the significance of good grades. Joe won his varsity letter in the last baseball game of the season against Yale as a bench substitute. Although he struck out at bat, he did end the game by tagging the Yale runner. Pocketing the winning ball, which by rights belonged to the Harvard team captain, Kennedy ran off the field with his captain in hot pursuit. Joe had his father’s lust for wealth and advancement—but lacked P.J.’s soul. Most remembered for his larger-than-life personality, and always eager to press his case for social advancement, Kennedy was rough—perhaps a rough diamond. His peers often recalled his profanity, toothy smile, quick wit, quicker temper, ready charm with the girls, brawling, and dedicated organizational skills in his “not-to-be-denied pursuit of wealth.” Odd jobs abounded in Joe’s youth, as P.J.’s obsession with status and money were ingrained in his son; just as Joe’s own obsessions would be visited upon his children. They would not be outsiders like he was.

Shortsighted since a young man, wearing his horn-rimmed round glasses long before they were fashionable, Kennedy was farsighted when it came to making money. Back then, banking was still a time-honored profession, and an attractive one to a young man lusting after riches. So, with help from P.J. and his friends, Joe became a bank examiner. Not only was he paid handsomely, but his raw intelligence taught him how the whole monetary system worked.

When the tiny Columbia Trust Company in East Boston (in which P.J. held a majority interest) looked as if it might be gobbled up by a larger competitor, P.J. sent out the call to his henchmen for cash. Joe got his old Harvard classmates to back him to become “the youngest bank president in the nation” at Columbia Trust, too. Some may not have liked the cocky young Kennedy, but all recognized a born money-spinner when they saw one and hopped on board.

From his youngest days, Joe longed to be an “insider” at the top man’s table. That meant marrying up the social ladder. And so Honey Fitz’s eldest daughter and college girl, Rose Fitzgerald, became the object of his affections. Rose was two years younger than Joe, and he had been courting her since his junior year at Harvard. It was only when Joe became the youngest bank president at age twenty-five that the mutual dislike between Honey Fitz and P.J. melted. The wedding took place on October 7, 1914. Joe would always address his father-in-law when writing as “Mr. Mayor.”

Within the year, Joseph Patrick Kennedy Jr. was born. Both grandfathers cooed and smiled over the baby’s crib, and Honey Fitz announced that he would be the first Catholic president of the United States. From that moment, Joe set his heart on making the name Kennedy as important to Americans as that other Boston name: Adams. Attaining that dream would be at the heart of Kennedy’s relationship—not had been courting her since his junior year at Harvard. It was only when Joe became America’s only with Roosevelt, but also with his sons.

Copyright © 2021 by Susan Ronald.

Born and raised in the United States, Susan Ronald is a British-American biographer, historian, and author of several books, including Conde Nast, A Dangerous Woman, Hitler’s Art Thief, and Heretic Queen. She lives in rural England with her writer husband.