by Tom Clavin

June 25th marks the anniversary of the Little Bighorn battle that resulted in the death of George Armstrong Custer and much of his 7th Cavalry command. The reason why this resonates with me—other than, of course, being an American history aficionado—is that with a co-writer and producer, Peter Israelson, I have been working on a limited series titled Crazy Horse and Custer: Vengeance On the Plains. It’s being shopped to production companies now and we’re hoping it finds a home.

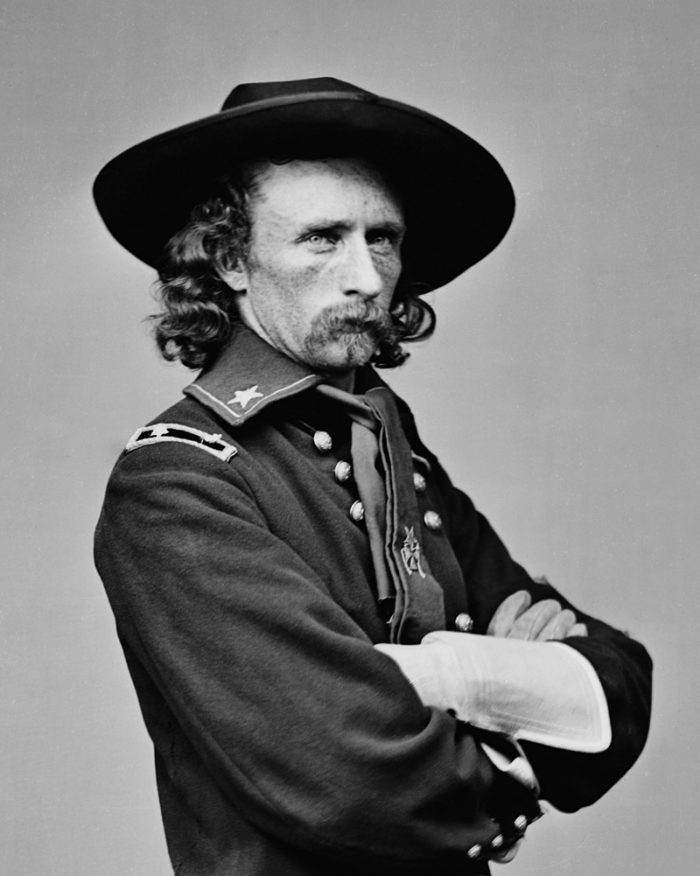

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

One reason why we’re confident it will is that it offers a serious and objective yet entertaining portrayal of Custer. He was certainly not a madman or a buffoon as he has too often been presented, such as played by Richard Mulligan in the film Little Big Man. Another reason is that westerns—or, at least, programs set in the American West—appear to be making a comeback on cable and streaming channels. A lot of this is thanks to Taylor Sheridan with Yellowstone and the other series it has spawned, but we’re seeing other projects finding outlets too. A third reason is our emphasis on the great Sioux warrior and mystic Crazy Horse. Lately, there has been an eruption of programs featuring Native Americans, including the excellent Dark Winds on AMC.

For your consideration and for the anniversary, here is the opening “pitch” of our limited series:

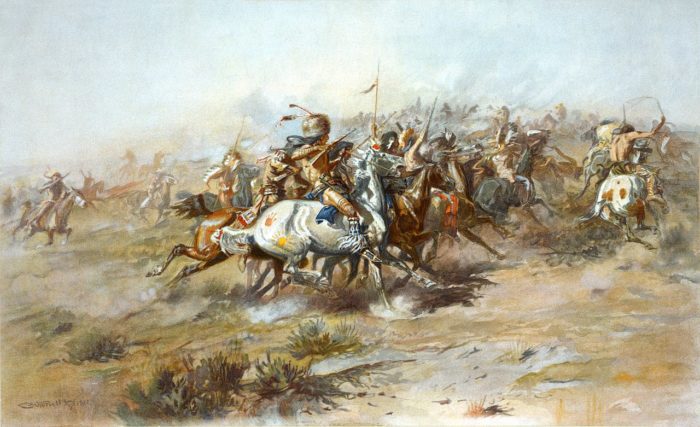

They kept coming at Custer—Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho—too many to count. Atop the hill on that bloody and boiling hot June afternoon, George Armstrong Custer and his brothers, Tom and Boston, and only a handful of others from the 7thCavalry were left. The air was saturated with the sounds of screaming, rifle cracks, and the bee-like buzzing of hundreds of bullets and arrows. As more bluecoats fell, as did his two flanking brothers, Lt. Colonel Custer, though still furiously firing his pistols, finally accepted there was no escape. Then, as though having read his thoughts, Crazy Horse, covered in painted hail stones, turned his pinto stallion back toward the top of the hill and made his final charge at “Long Hair,” the last man standing.

Surprisingly, in a culture that has often preferred legend over truth, some of what we know about Custer’s Last Stand is indeed true. But much isn’t. The famed Budweiser prints, which once hung in many a saloon across America, glorified Custer’s Last Stand into a Wild West apocalypse with Custer meeting his end much like matinee idol Errol Flynn did in They Died With Their Boots On—the way Americans like it best: against impossible odds. And that movie is already over 80 years old.

Then there is the rest of the story . . . the true story.

They are mythical figures of the American West, and their ultimate bloody showdown was the most famous post-Civil War battle ever fought on American soil. George Armstrong Custer and Crazy Horse. One died in a last stand on a hill overlooking the Little Bighorn River on June 25, 1876; the other was murdered a year later by vengeful Army officers. Both were the bravest and most charismatic icons of their times. At one time, every school kid knew what happened that fateful summer day; how the massacre happened; and why. Today, not so much.

There are now at least two generations—a big swath of America and, for that matter, the world—who don’t really know this story at all. They’ve heard the names—possibly even heard about the battle—but little else. That worldwide audience will be riveted by the actual tales of Custer, Crazy Horse, and the epic fight that’s one of America’s most dramatic passion plays. The Little Bighorn battle has never been accurately portrayed because what really happened that sun-scorched day in Montana, as the nation began to celebrate its Centennial, is far more breathtaking than anyone has yet imagined. It’s time for a vivid retelling, featuring the never-before-shown bios of two fascinating frontier figures and how they fatefully clashed.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

George Armstrong Custer was America’s first rock star. His picture was everywhere. Known as “Long Hair” because of his flowing locks, he emerged from the Civil War with the golden image of a fearless and dashing leader. As he prowled the Plains at the head of the 7th Cavalry, he was accompanied by the nation’s first paparazzi—a wagonload of embedded reporters and photographers. The breathless dispatches and images sent east were inhaled by an American public eager to know more about Custer’s fantastic exploits. He and his beautiful wife, Libby, were destined to become the Bill and Hillary of their time—after, that is, Custer returned from a successful 1876 Indian campaign. In fact, that coming November he hoped to succeed another war hero, Ulysses S. Grant, in the White House. Yet all that changed one hot June afternoon when Custer—the “Boy General”—unexpectedly morphed from hero to myth by colliding head-on with an Indian force led by a fearsome warrior conjured up in Custer’s worst nightmares: Crazy Horse. All that was required for Custer’s meteoric rise to immortality was his untimely death. According to those who found him, he died with a smile on his face—laughing in the face of death.

Crazy Horse—in the Lakota language, Tashunkewitko—was the most dynamic and revered Indian warrior ever. In popular culture, we know the names of Cochise, Sitting Bull, Quanah Parker, Geronimo, Chief Joseph, and Red Cloud, the great Lakota Sioux leader. For well over a century, we knew next to nothing about Crazy Horse. Like Custer, he too was long-haired, physically impressive, and utterly fearless. The Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, normally enemies, were all drawn to him. A fiery yet mystical man, Crazy Horse’s visions revealed the future—including the belief he could never be hurt by arrows or even bullets. Unlike Custer, he never allowed his picture to be taken—even once. And Crazy Horse never put his mark on any treaty, nor ever slept in any manmade bed. He was willing to die for his beloved Black Hills and all its creatures—lands and buffalo no white man should rightfully take away.

If Sitting Bull was the conscience of the Indian uprising, Crazy Horse was its lightning bolt—a stirring symbol he himself slashed on his own face before a battle. It’s astonishing how little anyone knows about this larger-than-life Indian warrior who not once, but twice, annihilated an entire American military force. (To enhance the authenticity of this new screen version, when Native American dialogue is necessary, it will be in Lakota with subtitles.) After June 25, 1876, the Indian Wars were no more. Native Americans were soon sadly reduced to wooden cigar store Indians or to feathered dancers selling rubber tomahawks at chamber of commerce functions. Even Sitting Bull did a stint in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show—all turned into living ghosts in their own land. In death, only Crazy Horse stayed defiantly true—in the proud Spirit of Crazy Horse.

Originally published on Tom Clavin’s The Overlook.

Tom Clavin is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and has worked as a newspaper editor, magazine writer, TV and radio commentator, and a reporter for The New York Times. He has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and National Newspaper Association. His books include the bestselling Frontier Lawmen trilogy—Wild Bill, Dodge City, and Tombstone—and Blood and Treasure with Bob Drury. He lives in Sag Harbor, NY.