by Thom Hatch

First Blood: Crazy Horse and The Battle of Rosebud Creek

Crazy Horse (Tashunka Witco, Tashunca-Uitco, “His horse is crazy”) was born about 1842 on the eastern edge of the Black Hills near the site of present- day Rapid City, Sioux Dakota. His mother was a member of the Brulé band, reportedly the sister of Spotted Tail, and his father an Oglala medicine man. Crazy Horse’s mother died when he was quite young, and his father took her sister as a wife and raised the child in both Brulé and Oglala camps.

Curly, as he was then called due to his light, curly hair and fair complexion, killed a buffalo when he was twelve and received a horse for his accomplishment. At about that time while residing in Conquering Bear’s camp, he witnessed the 1854 Gratten affair—where an army lieutenant named John L. Gratten and his twenty-nine men were slaughtered after a Sioux warrior had killed a stray Mormon ox and Gratten went to arrest him for the alleged crime. Curly also had viewed the destruction of the Indian village at Ash Hollow caused by General William Harney’s punitive expedition in response. Those experiences made an indelible impression on Curly and helped shape his militancy toward the white man.

Not long after the Gratten massacre, Curly sought guidance and underwent a Vision Quest by meditating on a mountaintop. He experienced a vivid dream depicting a mounted warrior in a storm who became invulnerable by following certain rituals, such as wearing long, unbraided hair, painting his body with white hail spots, tying a small stone behind each ear, and decorating his cheek with a zigzag lightning bolt. Curly’s father interpreted the dream as a sign of his son’s future greatness in combat.

The following year, Curly was said to have killed his first human. Curly was in the company of a small band of Sioux warriors who were attempting to steal Pawnee horses when they happened upon some Osage buffalo hunters. In the midst of a fight, he spotted an Osage in the bushes and killed this person, who, to his surprise, turned out to be a woman. It was not shameful in Sioux culture to kill a woman, but he was so upset that he refused to take her scalp and left it for someone else.

Curly proved his worth as a warrior when he was sixteen years old during a battle with Arapaho. Decorated like the warrior in his dream, he was in the thick of the fighting, scoring coup after coup, taking many scalps, but, to his dismay, was struck by an arrow in the leg. Curly wondered why he had been wounded when the rituals he had imitated from the warrior on his Vision Quest promised protection. He finally realized that his dream warrior had taken no scalps and he had. From that day forward, Curly would never again scalp an enemy.

He received a great tribute after that battle. His father sang a song that he had composed for his son and announced that the boy would now be known by a new name— Crazy Horse. Incidentally, that name was nothing special, rather an old, common name among the Sioux tribes.

Throughout the ensuing years, Crazy Horse had built a reputation among his people as a crafty, fearless warrior. He participated in many successful raids against traditional Indian enemies and the occasional small party of whites traveling through Sioux country but had not yet faced the might of the United States Army. In 1865, that would dramatically change when an endless stream of whites—gold seekers headed for Montana—flooded the Bozeman Trail and the army garrisoned several forts to protect them.

In 1866–67 during what became known as Red Cloud’s War, Crazy Horse was instrumental in rallying his fellow warriors and displaying an almost mythical courage and tactical craftiness. Due to Red Cloud’s leadership and the efforts of Crazy Horse, Hump, Gall, and Rain-in-the-Face the army finally admitted defeat and negotiated a treaty to end hostilities.

Crazy Horse, however, refused to “touch the pen” to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, disdained the reservation, and chose instead to freely roam traditional Sioux hunting grounds and wage war against the Crow and Shoshoni. It was said that during this time of wandering he married a Northern Cheyenne woman, which gained him friends and followers from that tribe. His interest in a certain Lakota Sioux woman, however, would nearly cost him his life.

Crazy Horse, who had gained the reputation of being introverted and eccentric, had ten years earlier vigorously courted Black Buffalo Woman, Red Cloud’s niece. At that time, however, she had spurned Crazy Horse in favor of a warrior named No Water. Gossip spread that Crazy Horse had continued to visit Black Buffalo Woman when her husband was away. In 1871, Crazy Horse convinced her to run away with him. No Water was incensed and set out on the trail, finally finding the couple together in a tepee. He shot Crazy Horse, the bullet entering at the nostril, fracturing his jaw, and nearly killing him. Crazy Horse gradually recovered from this serious wound. Black Buffalo Woman returned to No Water but some months later gave birth to a sandy-haired child who suspiciously resembled Crazy Horse. The Sioux warrior licked his romantic wounds and in the summer of 1872 married Black Shawl, who would bear him a daughter, They-Are-Afraid-of-Her.

The military had been encroaching on Sioux buffalo-hunting grounds for some time, and when George Armstrong Custer’s Yellowstone Expedition of 1873 served as escort for the Northern Pacific Railroad survey crews it has been said that Crazy Horse may have participated in the violent opposition.

The discovery of gold during Custer’s Black Hills Expedition the following year brought hordes of miners into that sacred Sioux region that had been promised them by the provisions of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Negotiations by the United States government to buy the land angered Crazy Horse and other free-roaming Sioux. The bodies of many miners—not scalped, which was Crazy Horse’s custom—began turning up in the Black Hills. Although no direct evidence exists, it has been widely speculated, even by his own people, that Crazy Horse was the one behind these brutal acts.

Another incident occurred about this time that had a profound effect on Crazy Horse. He was out fighting Crow Indians when his daughter died of cholera. The village had moved about seventy miles from the location of the burial scaffold on which lay They-Are-Afraid-of-Her. Crazy Horse tracked down the site and lay for three days beside his daughter’s body.

The United States government had issued the edict that all Indians in the vicinity of the Yellowstone River Valley report to the reservation by January 31, 1876, or face severe military reprisals. Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and others, however, ignored the demand and remained free.

Now, in the middle of the night and in the midst of a raging snowstorm Crazy Horse had come to the rescue of his people on the Powder River, recapturing the pony herd and salvaging whatever he could of the village.

General George Crook was furious with Colonel Reynolds for not holding the village. When the command returned to Fort Fetterman on March 26, Crook filed court-martial charges against Reynolds, who was subsequently found guilty of neglect of duty. Reynolds was punished with a one-year suspension from duty, which was eventually commuted by his former West Point classmate, President U. S. Grant. Reynolds, however, would be quietly retired on disability the following year.

On May 29, Crook, with a column consisting of fifteen companies of cavalry and five of infantry—more than one thousand men—once again departed from Fort Fetterman as a part of General Alfred H. Terry’s three-pronged approach designed to close in around the hostile Indians. Crook reached the head of the Tongue River near the Wyoming-Montana border on June 9 and established a base camp on Goose Creek while waiting for about 260 Shoshoni and Crow who wanted to take part in the campaign against their traditional enemies.

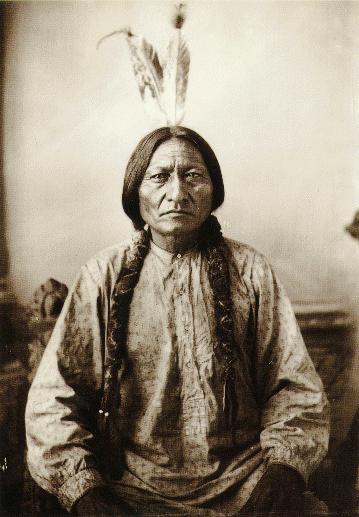

At about this time, the Sioux held a Sun Dance on the Rosebud. The highlight of this gathering was the revelation that revered medicine man Sitting Bull had experienced a sacred vision that would change history for the Lakota Sioux tribe and their allies.

Sitting Bull (Tatanka Yotanka, “a Large Bull Buffalo at Rest”) was born about 1830 at a supply site called Many Caches along the Grand River, near present-day Bullhead, South Dakota. He was the son of a chief named either Four Horn or Sitting Bull, and his boyhood name was “Slow” or “Jumping Badger.” At age ten he killed his first buffalo, and four years later he counted coup on an enemy Crow, an act that prompted his father to change the boy’s name to Sitting Bull. Also at about that time, he went on a Vision Quest and was accepted into the Strong Hearts warrior society. Sitting Bull proved himself a fierce warrior, gaining the utmost respect of his peers for his daring exploits, especially after he sustained a wound in battle with the Crow that forced him to limp for the rest of his life. He assumed leadership of the Strong Hearts at age twenty-two.

Sitting Bull subsequently led raiding parties of his warriors against traditional Sioux enemies, such as the Crow, Blackfeet, Shoshoni, and Arapaho. He eventually became known as someone special, a warrior whose medicine was good, and became a Wichasha Wakan—a man of mystery, or medicine man. He also became legendary for practicing the Sash Dance, where in the face of the enemy he pinned himself to the ground to indicate that he would never retreat.

Sitting Bull, who did not “touch the pen” to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, avoided any confrontation with the United States Army until the early 1860s when General Alfred Sully encroached on Hunkpapa territory in the Dakotas while pursuing Santee Sioux fugitives. He carried out hit-and-run raids on small army detachments and led his Strong Hearts at the July 28, 1864, Battle of Killdeer Mountain.

During Red Cloud’s War, Sitting Bull’s band roamed farther north, where he led attacks in northern Montana and Dakota Territory, particularly in the vicinity of newly constructed Fort Buford at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. Many Sioux gave up their freedom and moved onto the reservation when Red Cloud negotiated the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

Sitting Bull refused to submit and continued to follow the traditional nomadic lifestyle of his people. He and his band, however, would occasionally visit the reservation to obtain supplies and spread discontent among their brethren. His warriors were said to have been the Sioux who aggressively protested the presence of the army during Custer’s Yellowstone Expedition of 1873.

When Custer marched through the Black Hills the following year, Sitting Bull considered this intrusion and that of the prospectors who later came to dig for gold to be tantamount to a declaration of war. He assumed the position as head of the war council and gathered around him allies from the Northern Cheyenne and a few other tribes.

In his mind, war had been declared by the United States government when an edict was issued requiring all Indians in the Yellowstone Valley to report to the reservation by January 31, 1876, or face the consequences. This defiant spiritual leader had no intention of obeying the order.

It was during early June 1876 while camped in the Rosebud River Valley that Sitting Bull’s people held a Sun Dance. Sitting Bull did not personally participate in this ritual where warriors would have strips of rawhide attached to a stick and inserted into their chests, then dangle in the air from a center pole. Instead, he directed his adopted brother to slice strips of flesh from his arms and then commenced dancing until he passed out. When Sitting Bull was revived, he told of a vision that he had experienced: dead soldiers falling from the sky into their camp. This vision was interpreted to mean that they would be victorious in battle against their enemy.

The first opportunity to verify this vision came in mid-June when General George Crook’s troops were observed approaching on a route that would take them directly into a Sioux village.

Unknown to Crook, his presence was being closely monitored by Cheyenne scouts led by Wooden Leg. When Crook broke camp on June 16, those scouts determined that the army was following a trail that would lead them directly to Sitting Bull’s village, located a few miles north of present-day Busby, Montana. The Indians, concerned about the well-being of their families, held a council and decided that they would not wait for the army Crazy Horse with as many as one thousand Sioux and Cheyenne warriors would attack Crook’s column.

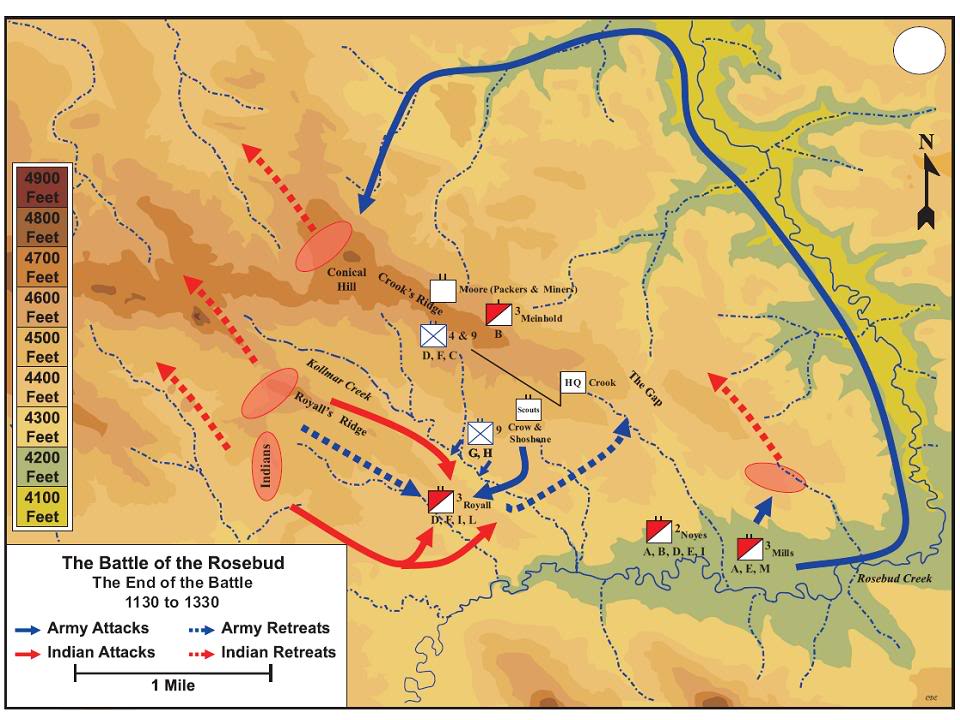

On June 17, Crook called a halt at mid-morning for coffee and to graze the horses in a valley of the Rosebud short of Big Bend. This cul-de-sac-shaped valley with steep walls was made up of broken terrain dotted with trees, bushes, ridges, and rock formations. It was sometime between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m. when Crow scouts raced into this camp from the north to spread the alarm that they had spotted a large body of hostile Indians.

Crook, however, would not be afforded the opportunity to assemble his troops in a battle formation or employ effective military tactics. Crazy Horse had departed from his customary tactic of circling around his prey from a distance and instead immediately followed the Crow scouts over the hills to lead his warriors on a charge into the surprised cavalrymen.

Due to the terrain, the fighting was reduced to small, hastily organized units engaging the determined warriors—at times hand-to-hand—at various locations around the three-mile-long field of battle. The Indians would hit-and-run, riding in and out among the troops, who would attempt to hold their positions against each onslaught.

As the battle ensued, Crook decided that the best defense was an offense. In an effort to divert the warriors, he ordered that a detachment led by Captain Anson Mills ride downstream and attack the Indian village that he incorrectly presumed was just a few miles away. Mills, with the promise that Crook would be following with the main column, rode down the valley, which as he progressed became narrower. He correctly assumed that Crazy Horse, the master of the decoy, had deployed warriors in ambush, and proceeded with caution. Mills eventually turned back from his harrowing ride, either of his own accord or perhaps with recall orders from Crook, and thereby escaped disaster.

The fierce battle had raged for perhaps as long as six hours or until mid- afternoon when the Indians began massing for one final concentrated attack. Crook, however, recognized the strategy and ordered Mills to maneuver his cavalry behind the Indians. Crook’s tactic was successful—his enemy broke contact and left the field to the cavalrymen, effectively ending the battle. The Indians later claimed that the reason they had fled at that point in time was because they were low on ammunition and their horses were worn out.

Crook proclaimed victory because his troops held the field at the end, but he had in truth fought to a stalemate at best. His fate might have been even worse had not the Shoshoni and Crow saved the day on more than one occasion with bold feats of bravery. The army’s casualty figures have become a matter of controversy. Crook’s official report stated that he suffered ten killed and twenty-one wounded. Scout Frank Grouard’s estimate of twenty-eight killed and fifty-six wounded would probably be closer to the truth. Crazy Horse later acknowledged that he had lost thirty-six killed and sixty-three wounded.

Rather than resume his pursuit of the hostiles, Crook chose to countermarch and return to his camp on Goose Creek to lick his wounds. Without notifying the other columns with whom he was expected to rendezvous in the Valley of the Little Bighorn, Crook had of his own accord taken his command out of action. Had he aggressively followed the fresh Indian trail, Crook would have likely arrived at Sitting Bull’s village on the Little Bighorn either before Custer’s Seventh Cavalry or in coordination with the other two columns, which had been the intention of General Terry’s plan.

Crook’s battalion would have the distinction of letting and shedding the first blood of the Little Bighorn Campaign. It would not be the only cavalry blood that would stain the ground in Powder River country.

THOM HATCH is the author of The Last Days of George Armstrong Custer: The True Story of the Battle of the Little Bighorn and nine previous books, including Glorious War: The Civil War Adventures of George Armstrong Custer and The Custer Companion: A Comprehensive Guide to the Life of George Armstrong Custer and the Plains Indians Wars. A Marine Corps Vietnam veteran and a historian who specializes in the American West, the Civil War, and Native American conflicts, Hatch has received the prestigious Spur Award from the Western Writers of America for his previous work. He lives in Colorado.