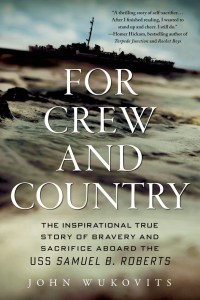

by John Wukovits

Chapter 1: “YOU ARE NOW A MEMBER OF A GREAT FIGHTING TEAM” The USS Samuel B. Roberts

Rarely has a hotel hospitality room held such a collection of unassuming sea warriors as the one that gathered in San Pedro, California, in August 1982. They had come from Utah and Virginia, Michigan and Arizona, and more than ten states in between. They set aside garage tools and law books, left schoolrooms, farms, factories, and police stations, and made room in packed schedules, because of their shared bond. As shipmates of the World War II destroyer escort USS Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413), they came to honor their skipper, Robert W. Copeland. His command of the feisty destroyer escort thirty-eight years earlier had catapulted him to the ranks of admiral and earned him the rare honor the United States Navy was bestowing that August 7, 1982: naming a warship of the fleet after him. The frigate, USS Copeland (FFG-25), would that day be commissioned.

Image is in the public domain via NavyBook.com

The aging men, most in their fifties and sixties, had shared the same dangers—some were, in fact, at his very side—in 1944 when Copeland turned his diminutive vessel toward those Japanese battleships and cruisers intent on annihilating his ship. Despite being badly outgunned, Copeland charged the foe in a David-and-Goliath feat that prodded one deputy chief of naval operations to call the vessel “the destroyer escort that fought like a battleship. They wanted to be with the Copeland family today, their skipper’s second moment of triumph.

They came out of respect and love, for their commander and for each other. Red Harrington, labeled “the bearded and tattooed Boatswain” by the ship’s newsletter in September 1944, was one of those venerable chiefs that helped every skipper run a ship. He was all navy, and his gruff ways and piercing glare had unnerved more than a few seamen, some of whom thought his flowing red beard gave him the visage of a buccaneer of yore rather than a navy chief.

Red had served aboard many ships and worked with various crews, but none topped that of the Samuel B. Roberts. He said that Copeland and his officers instilled a can-do spirit among the crew that “I have never seen excelled in all my years as a Navy man.” When Copeland promoted Harrington to boatswain’s mate first class, Harrington vowed to never let the man down, and he had “tried for the rest of my life to justify his faith in me.”

Image is in the public domain via Wikimedia.com

He wrote shortly after this initial reunion that after the war he tried to forget his experiences. “Then, at the reunion, after all those years, seeing all who were kids with me, doing such a wonderful job at being men, I felt such pleasure for having had the honor to know and serve with them.” Harrington added, “Those men on the Sammy B. were my family, my home; they were closer to me than I can say.… I now know men do not fight for flag or country or glory. They fight for one another. Any man in combat who lacks comrades who will die for him is not a man at all. He is truly damned.”

The tight bond was evident at the Friday evening banquet when, amid laughter and revelry fueled by friendship and a drink, Harriet Copeland and Suzette Hartley, Copeland’s widow and daughter, entered the room. Everyone turned to the pair and broke into a standing ovation, a mark of respect for the family members and of the fondness the men retained for their former skipper. To the aging sailors, Copeland stood for all that was noble in a man, all they had attempted to be during the war and afterward.

One by one the survivors walked to the front and shared a memory about their ship or took a moment to tell the others what the ship meant to them. They laughed—and Jack laughed with them—about Jack Yusen’s comical tendency to be Harrington’s daily target whenever the chief wanted another part of the ship painted, but they also spoke jealously of “Hollywood” Yusen receiving more mail from pretty girls than the rest did combined. They remembered Norbert Brady’s “Fantail Fellowship Club,” a group of sailors who gathered nightly on the ship’s fantail to sing, smoke, and chew over the day’s events, and talked about Jackson McCaskill spending more time in the brig than anyone else. They howled again at Charles Natter’s amiable teasing of everyone in the crew and grinned about the battle Lt. John LeClercq waged to grow a few whiskers on that baby face of his.

They agreed that on October 25, 1944, they waged a desperate fight against Japanese battleships and cruisers. They recalled the fear, the bravery, the torpedoes slicing through the waters, and the unrelenting screech of incoming shells.

Because of their experience they grasped better than most why William Shakespeare had chosen to forever memorialize another October 25. In the play Henry V, King Henry V of England utters a memorable speech to his outnumbered troops before leading them into the Battle of Agincourt on October 25, 1415. They understood why the famous bard, through Henry, had described the soldiers as “we few, we happy few, we band of brothers,” for like the British soldiers they, too, over the course of six months, had fashioned a band of brothers, this at sea. Like the British soldiers they, too, had faced insurmountable odds.

They would also privately agree, for most would never admit it publicly, with what The New York Times concluded shortly after the battle, that “the gallant action fought by this group—particularly the short-lived battle put up by the four ships that were sunk—will surely go down in American naval tradition as one of the most heroic episodes in our history.” They would agree with the heralded naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison, who labeled their actions against the Japanese on October 25, 1944, “forever memorable, forever glorious,” and with the acclaimed novelist Herman Wouk, who wrote that the vision of the Samuel B. Roberts charging through the waters straight at Japanese battleships and cruisers “can endure as a picture of the way Americans fight when they don’t have superiority. Our schoolchildren should know about that incident, and our enemies should ponder it,” for the action is “one that will stir human hearts long after all the swords are plowshares: gallantry against high odds.”

JOHN K. WUKOVITS is a military expert specializing in the Pacific Theater of World War II. He is the author of many books, including For Crew and Country: The Inspirational True Story of Bravery and Sacrifice Aboard the USS Samuel B. Roberts, Eisenhower: A Biography; One Square Mile of Hell: The Battle for Tarawa; and American Commando: Evans Carlson, His WWII Marine Raiders, and America’s First Special Forces Mission. He has also written numerous articles for such publications as WWII History, Naval History, and World War II. He lives in Trenton, Michigan.