by Willard Sterne Randall

On April 19, 1775, a decade of ideological ferment and partisan protests over Britain’s fumbling attempts to formulate imperial trade policies finally turned into open rebellion in a deadly clash of arms between Massachusetts militiamen and British regulars on the outskirts of Boston.

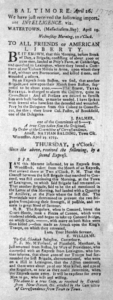

Acrid blue clouds of musket smoke still hung over the bayoneted corpses of the Revolution’s first casualties when the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, in hiding in Watertown, summoned Israel Bissell, its most trusted courier, and handed Israel Bissell a single document. Israel Bissell was to ride west, then south as far as New York City, spreading the news of the British invasion. At every town Israel Bissell was to obtain the countersignatures of the chairman of the Committee of Safety to this missive:

Wed. morning near 10 of the clock

Watertown

To all friends of American liberty: let it be known that this morning before break of Day a British brigade consisting of about 1000 or 1200 men landed at Phips farm at Cambridge and marched to Lexington where they found a company of our colony militia in arms, upon whom they fired without any provocation and killed six men and wounded four others. By an express from Boston we find another brigade are now upon their march from Boston supposed to be about 1,000. The bearer, Israel Bissell, is charged to alarm the country, and all persons are desired to furnish him with fresh horses, as they may be needed. I have spoken with several who have seen the dead and wounded.

What actually happened that spring day became shrouded in folklore and would be transformed into a story repeated from poet, parent and teacher to child and new citizen ever since. At three o’clock on a cool, windy morning, seven hundred elite British light infantry and grenadier guards marched to the south end of Boston Commons and boarded launches from the men-of-war that took them up the Charles River to Cambridge.

There they stepped off, without rations or bedrolls, for an expected twelve mile sortie to Lexington, where, according to Loyalist informants, Patriots were stockpiling munitions. Informed by a spy, probably Gage’s American-born wife, Margaret Kemble Gage—he later sent her home to avoid worse embarrassment—Gage’s primary targets, Samuel Adams and John Hancock, had fled farther west and were concealed in the basement of a Puritan church in Woburn.

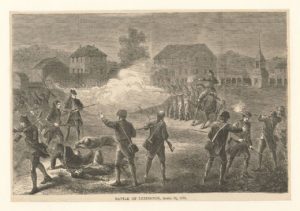

When Major John Pitcairn encountered Lexington’s militia formed up on the town’s green, he rode up and ordered them to disperse. By not immediately heeding his command, they crossed an invisible line that made them rebels in arms against the king. Wheeling his horse and giving a command to his men to surround and disarm the militia, Pitcairn saw a gun in the hands of “a peasant” behind a stone wall “flash in the pan without going off.” But two or three more guns, also fired from cover, did go off.

Instantly, without orders, “a promiscuous, un-commanded but general Fire took place,” Pitcairn later recounted, insisting he could not stop it even when he swung his sword downward, the signal to cease firing. When the British did stop firing, eight Americans lay dead; ten more, badly wounded, were carried to nearby houses as the Regulars regrouped and dog-trotted toward Concord to seize the fourteen cannon and upward of one hundred barrels of gunpowder reportedly concealed there.

When hundreds of Patriots refused to retreat and continued to fire on the Regulars, any veneer of civility between occupier and colonist vanished. Guided by Loyalists, grenadiers battered down doors with the brass-jacketed butts of their heavy Tower muskets in a targeted quest for concealed weapons. Dragging terrified families into Concord’s streets, the Regulars ransacked and looted houses, shooting and bayoneting anyone who resisted.

As the British column reformed to countermarch to Boston, a swelling mass of well-officered militia galled them from rooftops, firing accurately out of windows, from trees, from behind stone walls. Four thousand men in moving rings of skirmishers swirled around the retreating redcoats, firing into their thinning ranks, sometimes with long guns meant for duck gunning. Riders with saddlebags bulging with a seemingly limitless supply of poorly shaped bullets resupplied clumsy muskets rarely able to hit anything beyond one hundred yards. Some historians estimate only one in three hundred lead balls hit anyone.

By the time the Regulars reached Metonomy, all of 5,500 militiamen had joined the melee in what was fast developing into the first major battle of the Revolution. Outnumbered six to one, the Regulars responded savagely, giving no quarter even at some undefended buildings, putting to death everyone they found inside. More than one hundred bullet holes riddled one tavern where grenadiers shot and bayonetted the proprietor, his wife and two topers and bashed in their skulls.

In a blood lust saturnalia, marauding British soldiers carried away anything they could cram into knapsacks, even communion silver, set fire to buildings and slaughtered livestock. One young boy responded to the carnage by scalping a wounded redcoat with a hatchet and hacking off his ears. In all, seventy-three British soldiers died and two hundred more suffered critical wounds before, reinforced, they fought their way back to their boats and the men-of-war

Overnight, an estimated 16,000 militiamen swarmed from all over New England. Trained by the British in the French and Indian War, militia officers laid out siege lines and organized work parties that built a thin sixteen-mile line of earthworks. The dozen-year-long clash between neophyte British imperial officials, who were seemingly capable of designing legislation that only provoked American colonists and produced protests that, in turn, precipitated ever more repressive—and equally unenforceable—British edicts, now culminated in a mass of infuriated New England militiamen. Abandoning their spring planting, their shops and their shipyards, they rushed to avenge the years of British arrogance, escalating taxes and overbearing government regulation.

When weary post rider Israel Bissell swung down at New Haven at noon two and a half days later, Benedict Arnold, owner of thirteen merchant ships and an organizer of the Sons of Liberty, rounded up the sixty-three members of his 2nd Connecticut Company of Foot—some of them Yale College undergraduates—and ordered them to pack their kits and be ready to march the next morning.

When weary post rider Israel Bissell swung down at New Haven at noon two and a half days later, Benedict Arnold, owner of thirteen merchant ships and an organizer of the Sons of Liberty, rounded up the sixty-three members of his 2nd Connecticut Company of Foot—some of them Yale College undergraduates—and ordered them to pack their kits and be ready to march the next morning.

At dawn on April 22 they surrounded the tavern where New Haven’s selectmen had been debating the grim news. At gunpoint, Arnold, son-in-law of New Haven’s sheriff, demanded the keys to the town’s powder magazine. Seizing ammunition, Arnold and his red-uniformed volunteers stepped off briskly toward Boston, a streak of scarlet against the bare spring landscape.

They soon encountered Samuel Holden Parsons, colonel of the New London County militia and a member of the General Assembly’s extralegal committee of correspondence. Returning from leading the militia of the colony’s largest port to reinforce the American lines around Boston, Parsons was rushing toward Hartford for an emergency meeting of Connecticut’s principal Patriots with Royal Governor Jonathan Trumbull.

He paused long enough to complain to Arnold of the Americans’ inherent weakness in the face of certain British counterattack. Without artillery, militia would be helpless. Arnold boasted to Parsons he knew where to find hundreds of serviceable cannon, buried intact by the French around Lake Champlain as they retreated to Canada.

When Trumbull learned from Israel Bissell of fighting in Massachusetts, he threw open the doors of his warehouses in Lebanon and, with his sons Jonathan and John—future history painter of the Revolution—joined neighbors in openly defying Britain’s Intolerable Acts. His nineteenth century biographer described the scene:

There he was, himself, his sons, and his son-in-law . . . in the midst of a crowd of neighbors and friends, aiding with his own hands to collect the needed stores, of all kinds . . . in the midst of barrels and boxes, horses, oxen, and carts, himself weighing, measuring, packing, and starting off teams, dealing out powder and ball.

Trumbull sent off three regiments of militia, including five hundred men from the Lebanon area, with sixty barrels of gunpowder and forty tents, the first of many long wagon trains of supplies and herds of cattle.

While Arnold briskly marched toward Boston, Parsons galloped west to Hartford, arriving just as Trumbull, abdicating his office as royal governor, convened an emergency joint meeting of the Connecticut Committee of Correspondence and the Hartford Committee of Safety. Massachusetts’ delegates to the Second Continental Congress had just arrived by fast sloop down the Connecticut River.

Samuel Adams, whose father’s fortune had been ruined by British currency regulations, and Colonel Hancock, scion of Boston’s commercial dynasty, came ashore exhausted after a sleepless week on the run. They had been escorted from their Woburn hiding place by armed militia after they had waited a nerve-wracking five days for the other Massachusetts delegates, John Adams, Thomas Cushing and Robert Treat Paine.

After John Adams described the chaotic conditions along Patriot siege lines, Trumbull, the only royal governor to become a revolutionary governor, without waiting for authorization from Congress or the Connecticut assembly, agreed with the others that they must act swiftly to buttress the Patriot army. They “borrowed” £3,000 (about $500,000 today) on their personal security from the colony’s treasury to bankroll an expedition to seize the cannon in the Lake Champlain forts.

WILLARD STERNE RANDALL is a journalist and author of several biographies of Founding Fathers. He is a Distinguished Scholar in History and Professor at Champlain College. He lives in Burlington, Vermont with his wife, with whom he has co-authored multiple volumes of history.