by Nina Sankovitch

Taxes, duties, and the stationing of troops to enforce payment of both were all causes of the American rebellion against the British. But not the only causes.

In early fall of 1772, news arrived in Massachusetts that colonial judges would no longer receive their salaries from colonial legislatures. Instead, all judicial salaries would be paid by the King. In what came to be called “the Affair of the Royal Salary,” the response of the colonists was swift, widespread, and angry.[1]

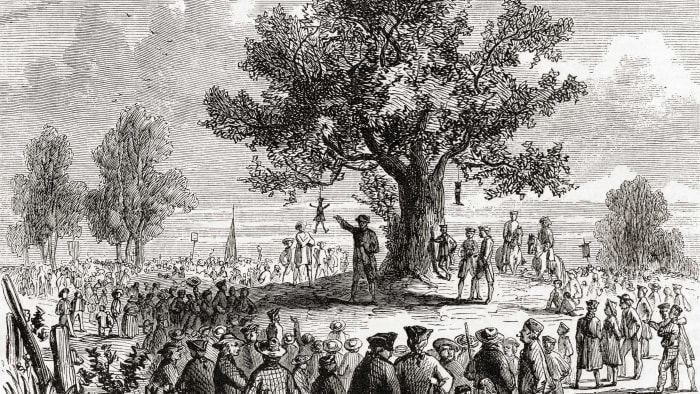

Cassell’s Illustrated History of England, 1865

In Massachusetts, judges had long been appointed by both legislators and the governor, and their salaries were paid by funds raised by the legislators. Because the legislators controlled the purse strings (the salaries), in some sense they controlled the judges – but both branches, judicial and legislative, largely considered the judges to be independent and therefore able to dispense impartial and fair justice.

With the new salary scheme forced onto the colony, however, colonists feared judges would no longer act impartially, especially in those cases concerning disputes between colonists and the King, such as the highly contentious issues of taxes and standing troops. As Josiah Quincy Junior, a leading political pamphleteer of the time, pointed out (in a series of explosive essays), it was of overwhelming benefit to the King to have colonial judges in his royal pocket: “So sensible are all tyrants of the importance of such courts, that, to advance and establish their system of oppression, they never rest until they have completely corrupted, or bought, the judges of the land. . . .”[2]

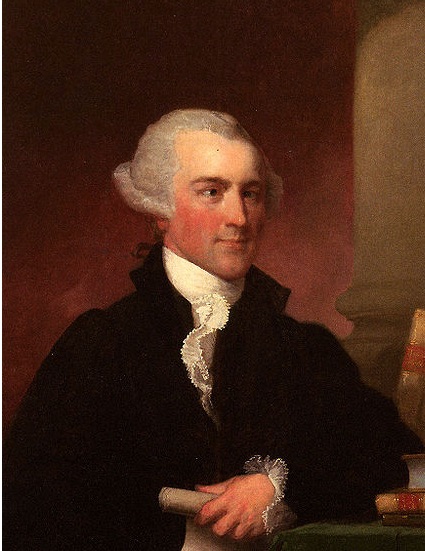

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts

“Who appoints, who displaces our judges, we all know. But who pays them?” Quincy asked. “The last vessels from England tell us—the judges and the subalterns have got salaries from Great Britain! Is it possible this last movement should not rouse us, and drive us, not to desperation, but to our duty?”[3]

The response of the judges themselves to the news of their newly-funded salaries was for the most part muted. But Chief Justice Peter Oliver publicly crowed over the new plan. For far too long, he had been dependent upon the whims (in his opinion) of the colonial legislators; in addition, his salary had remained consistently low (again, in his opinion). Now his salary would be guaranteed by the Crown and even better, Oliver was sure that his salary would rise (with additional increases every year) under the new regime. Oliver did not trouble himself over the issue of being beholden to the King in cases which challenged the colonial policies of Crown and Parliament.

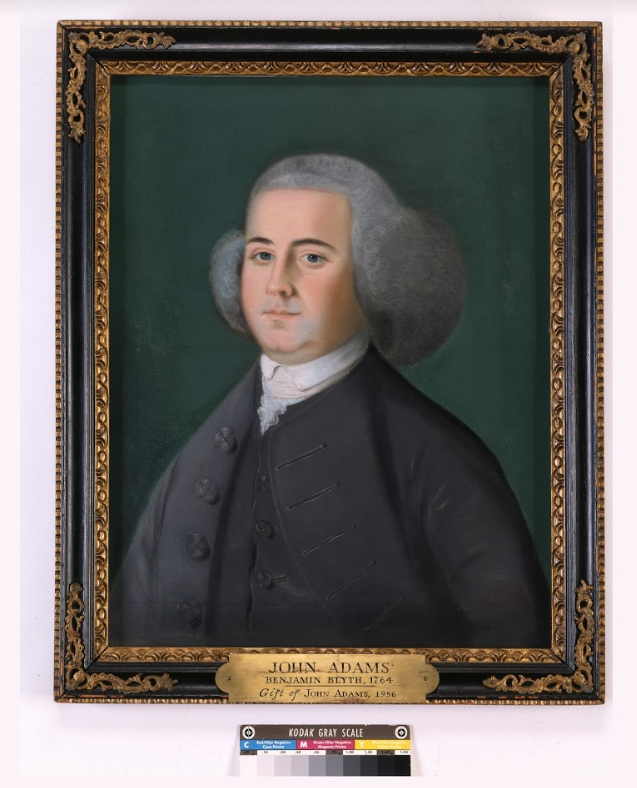

Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift of Mrs. Robert de W. Sampson to the Medical School, 1961

But the colonists of Massachusetts did trouble themselves over just such an issue. And they made trouble on the streets for everyone else. Mobs gathered in the evenings to stalk the streets, shouting about the injustices ravaged on the colony. Particularly rowdy types vowed to take Chief Justice Peter Oliver out to the Liberty Tree and let him swing from the branches until he repented of his evil ways.

Neither Josiah Quincy nor his friend and fellow patriot John Adams took part in the mob actions, nor did they support public threats made against Crown officials. They both believed the law could serve as a brake on corruption – and as Adams saw it, the method to do so was impeachment.

Under British legal precedents, public officials who had committed “high crimes and misdemeanors” in the undertaking of their duties could be impeached by the governing legislative body. Although there had never been any sort of impeachment case made in the colonies before, John Adams began researching how such a process might work, using impeachment cases that had been pursued in England as his model. He then set himself to work marshalling all the facts about Chief Justice Oliver and his actions on and off the bench.

One evening in early 1773, while attending a dinner party, Adams overheard a group of colonial leaders discussing the paying of royal salaries to colonial judges. He inserted himself boldly into the conversation and announced that he just might have the answer to the problem: a case of impeachment could be made against Chief Justice Oliver. If Oliver were successfully prosecuted, other judges would then refuse to take royal salaries. Adams’ suggestion was met with amazement. The gathered men asked him eagerly: could Adams himself draw up the papers?

Of course, he answered.

Within days (given that he had prepared his legal and factual research well in advance), Adams wrote the Articles of Impeachment against Peter Oliver. In his papers, John Adams argued that the most important duty of a colonial judge was to protect his fellow colonists against incursions into their rights and the deprivation of their liberties.

The Collections of The Massachusetts Historical Society

Adams then went on to describe the specific actions undertaken by Peter Oliver which demonstrated how he had violated his sworn duties. Among other charges, Oliver accepted the “Sum of four Hundred Pounds Sterling, granted by his Majesty…” and hoped for its future “Augmentation.” By doing so, he had committed the “high crimes and misdemeanors” of taking “a continual Bribe” in clear “Violation of his Oath.”

To make things even worse, Adams argued that Oliver had been compelled into “accepting and receiving the said Sum” by the “the Corruption and Baseness of his Heart, and the sordid Lust of Covetousness.”[4]

The Massachusetts legislators approved the Articles of Impeachment and quickly moved to distribute Adams’ impeachment papers throughout the colony. Colonists far and wide approved of the impeachment and roared for the removal of Andrew Oliver.

Thomas Hutchinson, royal governor of the colony, refused to recognize either the merits of the claims against Oliver or the legality of the impeachment. He declared that Chief Justice Oliver would not be removed, no matter how the legislators had voted or how loudly the colonists clamored.

But a judge without jurors could do little, and the colonists of Massachusetts were determined to never serve under a man like Peter Oliver. In the months that followed the impeachment, jurors called to serve in their local courts refused to participate, arguing the system was tainted by an impeached chief justice. As one man testified in Boston, “we believe in our consciences, that our acting in concert with a court so constituted… would be betraying the just and sacred rights of our native land… [which we need to preserve for] our posterity.”[5]

Without jurors, no cases could be heard, and the colonial court system was brought to a standstill. The disruption of British rule in the colonies was now on a roll. Taxes would not be paid, tea would be tossed into the sea, British troops on the streets of Boston would be harassed and hassled. The first steps on the road to revolution had been taken, and there would be no going back.

Nina Sankovitch is the author of several nonfiction books, including American Rebels and The Lowells of Massachusetts. She has written for the New York Times, the Huffington Post as a contributing blogger, and was formerly a judge for The Book of the Month Club. A graduate of Tufts University and Harvard Law School, Sankovitch grew up in Evanston, Illinois, and currently lives in Connecticut with her family.

[1] See Barbara Aronstein Black, “Massachusetts and the Judges: Judicial Independence in Perspective,” Law and History Review, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring, 1985), p. 101.↩

[2] Memoir of the Life of Josiah Quincy Junior (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1875), p. 52.↩

[3]Ibid, p. 53.↩

[4]Papers of John Adams, vol. 2, February 24 1774, Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.↩

[5]Peter Force, American Archive: A Documentary History of the English Colonies in North America, series 4, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1848), p. 749.↩