by Nick Irving

Timing is Everything: from the book Way of The Reaper

As soon as we were on the tarmac of the airfield, mortar rounds came in on our position. I (Nick Irving) thought again about our HVT and what seemed to be his sixth sense. As I hustled aboard the Chinook, I wondered if maybe somebody was tipping him off — one of the Afghan interpreters? Some other local who worked with us or for us? Seemed too coincidental that as soon as we were off to get a bad guy, explosive rain came down near us. In keeping with our time-sensitive mission, the chopper pilots did their part to deliver us to the landing zone as quick as possible. As much as I have a fear of heights, I liked it when the pilots employed their map-the-earth routine. That meant low-altitude flying, adjusting the craft’s flight for terrain and man-made obstacles.

At other points in the quick flight to the LZ, we climbed steeply. A bit of a roller- coaster ride, but varying our altitude was just another way to keep safe. As soon as the skids hit the ground, we were sprinting off that bird. We didn’t take any time to do any real observation/reconnaissance. The compound was in the middle of a clearing. Trees framed the clearing. Half our team had been dropped off on the far side of the objective, approaching from east to west. We were running through a freshly tilled farm field. The dirt was soft and furrows staggered us and made the going especially tough. I tried to take my mind off my burning thighs and hamstrings by visualizing what it must have looked like for us to come in low and fast, burst out of the chopper, and take off like we were a bunch of Delta guys. Should have used us for a recruitment video.

As we got within a few hundred yards of the objective, I was able to make out some of the features I’d seen back in our brief. I started counting the small buildings dotting the compound, orienting myself to their positions relative to the objective and to one another. It was clear that this wasn’t organized like the orderly subdivisions back home, with each house aligned with every other one, all of them with their entrances perpendicular to grid like streets. Instead, it looked as if the wind had blown and scattered them across this high-desert landscape.

The buildings were clustered in a loose circle, like a cog gear with a few teeth missing. I spotted the one at roughly nine o’clock that I’d identified as the best position for Wayne and me. I started angling toward it. The ground beneath our feet had gone from tilled soil to hard-pan; now we were on to loose stones (“baby heads,” some guys called them), rocks the approximate size of a newborn’s skull. They led down to an irrigation ditch. I was slip- sliding along them, cursing under my breath, but when I looked to either side of me, I didn’t see any rocks at all. What the hell?

My geological contemplation was cut short by the sound of tracers overhead. Good thing I’d gone down that incline and wasn’t any taller. I threw myself against the far side of the ditch and hunkered down. We were taking fire, and because we were so near to being sent home, and it was so soon after one of our guys, Benjamin Kopp, had been killed in action, I was really, really in no mood for being shot at. Screw the whole acting- like- a- superhero thing I had once done. I was staying down until there was a lull in the firing. Time was slipping away, but what good would it do to get myself shot and impact the operation by having to have guys come in to help me? There’s a time for everything, I reminded myself.

When the first lull came, I jumped up and quickly fired a few rounds without aiming. I also took that opportunity to survey the scene. Ahead of me our assaulters weren’t taking their time like I had been. They were advancing, taking a knee to fire, advancing. We had to be there in support of them, so I motioned to Wayne (who was doing the right thing by hanging back behind me) that we had to join them. It was like we were all engaged in a game of leapfrog. Run. Crouch. Run. Crouch.

Even before I reached the sniper perch I’d decided on, I heard the sound of the flash bombs and other concussive and explosive devices.

“Shit,” I thought, “the other teams are starting. We should have been up on a roof doing our job.”

I had to make a quick call.

“Up here. Now,” I said to Wayne.

He turned to me, and I unsnapped the ladder and leaned it up against the wall. Instead of being at the nine o’clock, we were somewhere between six and seven. As soon as I had a moment, I got on the radio to alert the team leaders and everyone else on the main radio frequency of the change in my location. I wanted all the friendlies to know where Wayne and I were. On some operations, I lived in fear that some guy’s comms would be down and he wouldn’t get the message, then he’d see a figure up on a roof with a weapon and decide to take a shot at me.

I started up the ladder, and when I got to the top I extended my left hand beyond the ledge, expecting to reach the roof; instead, I reached nothing but air. I clambered back down and said to Wayne, “There’s no roof. We’ve got to get up somewhere. Now.”

We each grabbed an end of the ladder and took off running. As much as I hated that there was no roof there, I took a moment to survey the scene as we ran. We were losing time, but at least we were gaining intelligence. I detected movement to my left, in the trees, just north of where we’d come in through that plowed field. I knew that this situation was about to get bad, but at least I knew it. I got on the radio and reported what I’d seen. The assaulters were busy, occupied with going from building to building. I could hear them doing their thing— breaching the doors with C-4, popping flash bombs, yelling. Our target must not have been in the first three buildings I heard being cleared. But I needed to see our guys at work and not just hear them.

Wayne and I pulled up at the original building I had ID’d as my position. I went back on the radio to alert everybody. I came up with a game plan on the fly and shared it with Wayne. We were three hundred yards from the tree line and half that distance from the house that was the original objective. That objective was surrounded by a waist- high wall. Wayne joined me on the roof.

“I may be moving around some, but you’ve got to keep your eye on that ladder. Make sure nobody takes it.”

I’d heard of the bad guys doing that a few times and I didn’t want to be stranded up there, or have to jump down, or have to climb off that roof and really expose myself to the enemy.

“If we start to take fire from below, from inside this house, you get the hell off this roof instantly.”

Along with my fear of friendly fire was another fear. If we were on top of the bad guys and they heard us up here, what was to keep them from firing through the mud roof to take us out? If that kind of fire started, I’d be able to get to the ledge, where the wall met the roof, and have a better chance of not getting hit. Even better, instead of tactical boots, which would have offered good protection but were loud, I always wore soft- soled shoes. I tiptoed all around those rooftops like a stealthy cat.

We took up our positions and watched the assaulters do their thing. Even though we were really in a hurry and these guys were moving fast, it wasn’t like they were rushing at all. I’ve heard athletes say that in the middle of all the action in a game, they see things as moving slowly. I experienced that a lot overseas when we were in contact with the enemy. The action seemed to slow down, but time was still moving normally. I watched the assaulter move in, take off his backpack device, stick it to the door frame, and then look overhead at me. He gave me the thumbs-up and I returned it.

“Roger that, I got you,” I heard him say over the comms. “You might want to hunker down for this one. It’s a big one.”

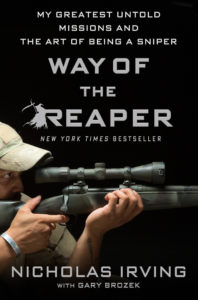

NICHOLAS IRVING spent six years in the Army’s Special Operations 3rd Ranger Battalion 75th Ranger Regiment, serving from demolitions assaulter to Master Sniper. He was the first African American to serve as a sniper in his battalion and is now the owner of HardShoot, where he trains personnel in the art of long-range shooting, from olympians to members of the Spec Ops community. He also appears as a mentor on the Fox reality show American Grit and is the author of WAY OF THE REAPER: My Greatest Untold Missions and the Art of Being a Sniper. He lives in San Antonio, Texas.

GARY BROZEK has co-authored 20 books, including five New York Times bestsellers.