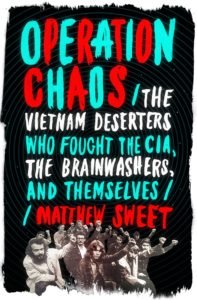

by Matthew Sweet

Stockholm, 1968. A thousand American deserters and draft-resisters are arriving to escape the war in Vietnam. They’re young, they’re radical, and they want to start a revolution. Some of them even want to take the fight to America. The Swedes treat them like pop stars—but the CIA is determined to stop all that.

It’s a job for the deep-cover men of Operation Chaos and their allies—agents who know how to infiltrate organizations and destroy them from inside. Within months, the GIs have turned their fire on one another. Then the interrogations begin—to discover who among them has been brainwashed, Manchurian Candidate-style, to assassinate their leaders.

When Matthew Sweet began investigating this story, he thought the madness was over. He was wrong. Instead, he became the confidant of an eccentric and traumatized group of survivors—each with his own theory about the traitors in their midst.

All Sweet has to do is find out the truth. And stay sane. Which may be difficult when one of his interviewees accuses him of being a CIA agent and another suspects that he’s part of a secret plot by the British royal family to start World War III. By that time, he’s deep in the labyrinth of truths and half-truths, wondering where reality ends and delusion begins. Keep reading for an excerpt of Matthew Sweet’s Operation Chaos: The Vietnam Deserters Who Fought the CIA, the Brainwashers, and Themselves.

The High Road

A Japanese fishing boat, moving north to Soviet waters. Six Americans in the forward hold below the captain’s cabin. Trying to stay warm. Trying to keep their nerve. Trying not to vomit too loudly. One is too drunk to feel seasick. He’s up on his feet, swigging from a bottle of sake, peering into the moonless night, swearing he can see dolphins in the water and helicopters in the sky. The others don’t bother to look. But when the beam of a searchlight streams through the crack in the door, all six scramble to the porthole, jostling to catch sight of the ship that has come down from the ice floes to meet them.

“It’s them, man,” says one. “The Russians are coming. We gonna be free now, baby.”

Most of us would find it hard to pinpoint the single act that determined the course of our lives. Mark Shapiro can reenact his with the cutlery. When we spent the day together in San Diego, he collected me in a cream-colored vintage Volvo wagon, which was where most of our interview took place—stationary in the hotel parking lot or riding around the streets, where other drivers expressed their admiration for the age of his vehicle by beeping their horns and keeping a wary distance. But we did stop for lunch. And using the implements with which he was about to eat pasta, Mark illustrated the moment during the small hours of April 23, 1968, when he crossed from one life to another.

His knife and fork became two ships on the churning waves of the Sea of Japan. One was the fishing vessel that brought him and his five companions from a little harbor at the northeast tip of Hokkaido island. The other was the Soviet coast guard craft that edged alongside, and that, slammed by the relentless sea, appeared like a cliff soaring and sinking before them.

Between the two vessels was a six-foot span of furious air, through which Mark and his comrades were ordered to jump. Time was limited. The coast guards had boarded the fishing boat and were inspecting the captain’s paperwork and checking the hold for contraband, the bureaucratic pretext for maneuvering so close. The Soviets had dragged a mattress to the cutter’s deck of their ship and were holding it up like a firefighters’ life net. One by one, displaying varying degrees of bravado and terror, the Americans slithered across the fishing boat’s deck and around a funnel to reach an area unprotected by railings and open to the sea. One by one they jumped. Into the arms of a gang of Russian sailors, and into history.

It took three years to persuade Mark Shapiro to meet me. His first email was a blunt rejection. “I do not wish,” he wrote, “to be contacted again on the matter.” But the deserter grapevine brought him news of my inquiries and he changed his mind. Intimations of mortality also had something to do with it. Mark’s health was fragile. He had heart trouble, and he slept with an oxygen cylinder by his bed. A tumor, he said, was growing in his skull. (He traced his finger over the place where it lay buried.) He knew that his time was limited and wanted to answer a question that was gnawing away at him. He wanted to expose the mole within the American Deserters Committee. His suspect was not among the five who traveled with him from Japan. The man upon whom Mark’s suspicions turned—the man he’d been trying to catch out for years—had arrived in Sweden months before him, and he was one of the founders of the ADC. I said I would do my best.

I knew the bones of Mark’s story from the accounts of his peers. On his tour of duty with the army in Vietnam, he’d found it hard to stomach talk of “gooks” and “slant-eyed bastards.” Then, out on patrol one day, the soldier beside him was felled by a Viet Cong bullet. A murderous wake-up call for twenty-two-year-old Corporal Shapiro, with an unblemished service record and good prospects for promotion as a military cryptographer.

I was ready to take down more details, but Mark seemed incapable of fleshing out his narrative. Instead, he told me a story about his recent visit to a hypnotherapist.

“I told him that there was something in my past that I wanted to remember,” he said. “And I didn’t tell him any more than that. The guy was a little skeptical. He asked for the money in advance.” The next thing Mark remembers is having his cash pressed back into his hand, and the therapist, visibly perturbed, assuring him that some stones were best left unturned. “So,” Mark told me, with a shrug, “I have nothing to say about Vietnam. It’s a form of amnesia.” I accepted the explanation. I was already used to thinking of my interviewees as jigsaws with missing pieces.

Mark’s decision to desert was not so lost to him. It was a textbook example of the act. In the first days of 1968, he read a newspaper article about four men who had successfully escaped the war. They had been on leave in Japan but were now poised to begin new lives in neutral Sweden. Their names were Craig Anderson, Rick Bailey, John Barilla, and Michael Lindner, but the press nicknamed them “the Intrepid Four,” after the U.S. aircraft carrier that had sailed without them from Yokosuka, the Japanese home of the Seventh Fleet. Another expression was also used to describe them. Defectors. Used in recognition of what many saw as an act of treachery.

On their journey from east to west, the Intrepid Four had passed through the Soviet Union and accepted several weeks of Russian hospitality. Maybe more than hospitality. They had shared their anti-war sentiments with the international press, attended celebrations for the fiftieth anniversary of the Russian Revolution, shaken hands with members of the Politburo, and flown from Leningrad to Stockholm with a$1,000 stipend from the Kremlin in their pockets. But they looked pretty happy in the photographs, waving and smiling on the tarmac at Stockholm Arlanda Airport, with their neat new haircuts and sharp new suits. And nobody was asking them to kill anyone in an increasingly unpopular war. Mark decided to follow their example and booked himself some R & R in Tokyo.

The news reports offered another helpful detail. The Intrepid Four did not make their journey unaided. They had been smuggled into Russia by an outfit called Beheiren, a group of activists who were fast becoming the focus of the Japanese anti-war movement. Beheiren had organized a rally in Tokyo at which Joan Baez had performed. It had taken out full-page ads in the Washington Post declaring that percent of the Japanese population was opposed to the Vietnam War. It had sent its members to U.S. naval bases with leaflets encouraging sailors to desert, intending to make a provocative gesture—and had been rather surprised to find the offer being taken up. All over Japan, doctors, teachers, shopkeepers, and Buddhist monks began preparing hiding places and airing the spare bedding.

Beheiren, however, was a loose-knit organization, and when Mark arrived in Tokyo, determined to make contact, nobody seemed to know its address. “So,” he explained, “I got into a cab and just said, ‘Beheiren.’ ” The driver thought for a moment and made for Tokyo University and the office of Oda Makoto, a Harvard-educated novelist and academic who was the group’s most visible spokesperson—the man who had gone before the cameras to announce the disappearance of the Intrepid Four. Makoto made some calls, and his associates sprang instantly into action.

By the end of the day Mark had checked out of his hotel and was installed in a Beheiren safe house. He soon discovered that he wasn’t the only deserter being sheltered by the group. Five others were also in hiding, kept in circulation among the homes of sympathizers across Japan until the time was right to make the journey to Russia. “When I eventually met the others it was a shock,” Mark said. “We had nothing in common, and it was immediately clear that two of them were nutcases.”

His first American companion fit squarely into the category. Philip Callicoat was a nineteen-year-old sailor whose swaggering manner was at odds with his lowly status as a cook’s helper on board the USS Reeves. Perhaps the attitude was a gift from his background: his father was a Pentecostal minister who press-ganged his enormous brood of children into service as the Singing Callicoats—a gospel act best known for having saved Ed Sullivan from humiliation by breaking into an unscheduled second number when a chimp act went badly wrong during a live TV show. Phil Callicoat had turned up at the Soviet Embassy seeking advice on how to defect, but his motives had less to do with politics and more to do with having drunk the last of his $120 savings in an all-night Tokyo jazz bar. Navy discipline did not suit him, and he had recently been confined to his ship for twenty-eight days for vandalism. He and Mark were brought together on a train from Osaka to Tokyo, then put up for the night in the apartment of a visiting French academic. Mark sensed that Phil was going to be trouble, and he was right.

The fugitives were taken to Tokyo International Airport, where three more deserters made a party of five. The noisiest was Joe Kmetz, a bullish New Yorker whose opposition to the war, he said, had earned him a month in a dark isolation cell on a diet of bread, water, and lettuce heads. The oldest of the group, twenty-eight-year-old Edwin Arnett, was a skinny, stooping Californian who chewed his fingernails and spoke in slow, somnolent tones. He was not a clever man. His educational progress had halted after the eighth grade, after which he’d trundled gurneys in a New York hospital and spent two years in the merchant marine. The army had expressed no interest in him until 1967, when a Defense Department initiative called “Project 100,000”—cruelly nicknamed the “Moron Corps”—admitted a huge swathe of low-achieving men. The other deserters called him “Pappy”—partly in honor of his age, partly to distance themselves from his oddness.

The sanest of the gang, it seemed clear to Mark, was its only African American: Corporal Terry Marvel Whitmore, a marine infantryman from Memphis, Mississippi, who had been wounded in action in Vietnam and received a Christmas bedside visit from President Lyndon B. Johnson, who saluted his bravery and pinned a Purple Heart to the pillow. When Whitmore learned he was also to receive the honor of being returned to the front as soon as he was upright, he discharged himself from the military hospital at Yokohama and lay low with a Japanese girlfriend, pretending to anyone who asked that he was a student from East Africa—and hoping not to encounter any actual East Africans.

Their Beheiren guide, a Mrs.Fujikowa, encouraged the deserters to behave discreetly on their trip. Easier said than done. As they boarded the plane, Mark got into an argument with the flight attendant about the size of his suitcase. When they landed at their destination, Nemuro airport on the island of Hokkaido, Phil Callicoat struck up a loud conversation with a local bar owner whose establishment offered more than just cocktails.

Before they could get into any serious trouble, the deserters were steered toward a pair of waiting cars and driven for four hours to a remote spot on the coast, where a gaggle of Beheiren sympathizers were huddled around a radio unit, exchanging messages with a Soviet ship—which informed them that the handover would have to wait until the following night. The plan postponed, the Americans were taken to a nearby fishing village, where the captain of their escape vessel was waiting at his home to greet them. He poured out the sake and told his nervous guests not to worry. He had been a kamikaze pilot in the Second World War, and he had come back.

The following night, the captain supplied the deserters with a change of clothes calculated to increase their chances of passing as Japanese fishermen during the short walk from his house to the floodlit harbor. Terry Whitmore wrapped himself in a blanket to conceal his conspicuous blackness. Fortified with more alcohol, the deserters went out into the freezing night and climbed aboard their host’s fishing boat. They were told to stay belowdecks and keep quiet: most of the crew were unaware of their existence. As the vessel began chugging from the harbor, a sixth man stumbled into the hold: army private Kenneth Griggs, born in Seoul but adopted as a baby by a white couple from Boise, Idaho. Griggs—who introduced himself under his Korean name, Kim Jin-Su—had spent the better part of a year hiding out in the Cuban Embassy in Tokyo, and he seemed to have made good use of the free literature. His reasons for desertion were expressed as an intense critique of U.S. imperialism. He had a position to maintain: he had already said his piece in a four-minute film, shot by Beheiren and screened for journalists in a Tokyo restaurant.

When the Russian coast guard pulled alongside, Kim was the first to jump, leaping with reckless enthusiasm into Soviet-administered space. Joe Kmetz, his fears numbed by alcohol, went just as eagerly. Callicoat followed, sliding across the deck and launching himself with a Tarzan yodel. Mark went next. Hesitated. Watched the rust-marked hull of the Russian ship surge up and down before his eyes. “Jump, you dumb cunt!” shouted Kmetz, unsympathetically. Arms flailing, Mark made it, his suitcase tossed after him by the Japanese skipper.

Edwin Arnett, though, was in a worse state, paralyzed by the sight of the rising, falling ship. Whitmore muscled past him, hurled himself across the divide, and was caught by two burly Russian sailors before he hit the deck. Left behind, Arnett seemed unable to compute the physics of the situation. Instead of jumping as the Russian ship fell, he jumped as it rose, colliding with the railing and leaving himself dangling over the sea by one leg. Whitmore and one of the Russians dragged him back to safety.

The Soviet ship was old. The plumbing hissed and thudded. The deserters registered the signs in Cyrillic and knew that they had passed from one political sphere to the next. But the Russians made them comfortable, allocating the deserters quarters beside the officers and giving them as much vodka as they could hold. For their whole time in the Soviet Union, it seemed to Mark, they were carried on a small river of colorless alcohol. “I guess,” he reflected, “they thought it would increase the amount of careless talk.”

There were toasts at dinner. To each other. To the interpreter, an incongruously flamboyant man with a cigarette holder. To the captain, who ended the meal by challenging his guests to a drinking game. Only Callicoat accepted, pushing a hunk of black bread inside his mouth and taking a huge slug of some unidentified spirit. He was soon carried back to his bunk.

For four days and nights the deserters knocked back vodka, dined on salmon, looked through the portholes, and watched the thickening ice. The interpreter took the opportunity to steer each man away from the group for a thorough discussion of his background and history. On April 25 the ship neared the coast of Sakhalin island, where a patrol boat brought the passengers ashore. Officials confiscated their passports and identity papers. A doctor examined Arnett’s injured leg and shrugged.

Then, for four dizzying, vodka-sluiced, bouquet-filled, flashbulb-illuminated weeks, Mark Shapiro and his comrades went on a publicity tour of the USSR: Vladivostok, Moscow, Tbilisi, Gorki, Leningrad, with a short break in the Black Sea resort of Batumi. They accepted flowers from little girls. They saw circus shows. They browsed at the GUM department store. They visited Lenin’s tomb. (“Who’s Lenin?” asked Terry Whitmore.) They saw more circus shows. All under the supervision of a small staff of well-mannered KGB officers and neckless security men in Al Capone fedoras. Some of the security men, they learned, had also kept an eye on the Intrepid Four. One had been taught a single phrase of English, which he repeated over and over again: American cinema—I love you.

In Leningrad the deserters were installed in the Hotel Astoria, where Mark shared a room with Terry Whitmore. “Terry could hear this whining noise,” Mark recalled. “He was convinced that the Russians were bugging the room. So he turned everything over, looking for a hidden microphone. But it was only the sound of the elevator. Just being in Russia made us all nervous.”

Their edginess caused conflict: Kim and Callicoat got into a fistfight, apparently over Kim’s plan to acquire and burn an American flag. On the rare occasions they were allowed to wander about on their own, the deserters assumed they were being followed. Assumed, too, that they were being informed on by the local women who were so eager to come up to their rooms—not least because they seemed so fascinated by the intricacies of the U.S. Navy. The minders never objected to these one-night stands, as long as they took place in the hotel. Conversely, when Whitmore and Kmetz broke bounds and spent the night with two women in an apartment, the security guys were not pleased and accused them of going out on a spying mission for the CIA. It wasn’t, it seems, a very relaxing evening: the women expected payment and though the Americans obliged, they were soon interrupted by a jealous husband, who upended the dining table in anger and then, rather more weirdly, began to show a gentle curiosity in the texture of Terry Whitmore’s hair.

The grand propaganda coup of the trip happened on May 3. The broadcast of We Cannot Be Silent, a half-hour television program in which the six deserters were interviewed about their experiences in Vietnam. Joe Kmetz, hiding under his shades, said the war was a sickness. Terry Whitmore compared the conflict in Indochina to the U.S. Civil War. Phil Callicoat read out a protest poem of his own composition. Kim Jin-Su played the ideologue, suggesting that a nuclear strike on the States might be the only way to defeat “stormtroopers and criminals who are carrying out Washington’s policy of annihilating the Vietnamese as a race and proud people.” He delivered his message down the barrel of the camera. “For those of you on the battlefields,” he said, “I would advise you to follow me and hundreds of others, and just remember that it may take guts to go, but it takes balls to say no.”

I asked Mark about his contribution to the film. “I said as little as I could,” he replied. “It was Pappy Arnett who did most of the talking.”

Arnett couldn’t shut up. In his droning monotone, he gave testimony that shocked and baffled the world. He said that he’d been trained at a special intelligence school at Fort Meade, Maryland, where he had learned forty ways of torturing a suspect. He said that he’d been assigned to a chemical warfare unit, and arrived on the coast of Vietnam aboard a ship loaded with gas that could cause hemorrhages, paralysis, and blindness. He spoke of salt water poured in the wounds of prisoners, of GIs making necklaces with the ears of dead North Vietnamese. He said that his commanding officer had “treated the sweeps we made through peasant villages as a turkey shoot”; described how the same officer had executed a Puerto Rican serviceman who refused to join the hunting party and then recorded the dead man as a victim of the Viet Cong; and reported that on another occasion, a superior had disemboweled a baby and thrown the tiny corpse back into its mother’s arms. The interviewer, Yuri Fokin of the Soviet television service, was silent. The camera operator began to weep. The other deserters were horrified. They might have been more horrified had they known the truth: that Edwin C. Arnett had been an army cook on board a floating maintenance shop moored in Cam Ranh Bay. The only violence he had witnessed in Indochina had been inflicted upon potatoes.

Vietnam was the place the bodies were buried or flown back from, the place where the bombs fell and the air burned. But the Vietnam conflict raged far beyond the borders of a former French colony on the South China Sea. It was an undeclared world war, fought between the representatives of two opposing ideologies to spare them the agony of adding Moscow, Peking, and Washington to a list that had begun with Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nothing about it was clean or uncomplicated. In 1954, the Geneva Accords split Vietnam into two zones, the Communist north, administered from Hanoi by the revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh, and the non-Communist south, ruled from Saigon by a succession of Western-backed leaders, who were advised—and sometimes hired and fired—by the hidden hand of the Central Intelligence Agency.

From 1960, the National Liberation Front, a Communist insurgency also known as the Viet Cong, added its firepower to the argument. Away from the bullets, the war’s foreign stakeholders invested their millions. China and the Soviet Union supplied expertise, money, and guns. The United States matched that commitment and, from 1965, sent roughly 2.7 million ground troops into the territory. Most found a place in the war’s decade-long ritual—boredom and terror in the battle zone, rest and recuperation in Tokyo, funerals and homecomings back in the States. But thousands of GIs rejected their roles and became deserters. The act carried the penalty of imprisonment and hard labor—and the possibility of becoming an unwitting combatant in the propaganda war.

As Mark Shapiro’s little platoon went in a vodka haze on their guided tours around Russia, Yuri Andropov, the head of the KGB and future leader of the USSR, must surely have permitted himself a smile of satisfaction, if not a high-kicking rendition of “Kalinka” on top of his mahogany desk. He and his colleagues had been expecting the deserters’ arrival since the first week of March. It had been their idea to use a Japanese fishing boat to transport the men. (The Intrepid Four had been put aboard a Soviet passenger steamer, which had caused some diplomatic awkwardness.) They had planned their itinerary, scheduled their media appearances, authorized the Novosti Press Agency to offer them a book deal. To obscure the KGB’s involvement, they had appointed a state-backed peace group, the Soviet Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee, as official sponsor of the trip. The Central Committee of the Communist Party had even discussed some of the deserters individually, causing phonetic Russian renderings of their names to be added to the Politburo minutes: Knet, Arnet, Kollikot.

During the first week of May 1968 those names chuntered from telex machines all over the world. America’s journalists went hunting for more details. A former Singing Callicoat responded to the sudden reappearance of her brother Phil: “I thought he was dead or we would have heard from him by now,” she said. “If it’s true, we disown him,” said Joe Kmetz’s stepbrother. But Arnett’s tales dominated the headlines, in all their wound-salting, village-burning, baby-killing horror.

Operation Chaos: The Vietnam Deserters Who Fought the CIA, the Brainwashers, and Themselves

Before the tour came to an end, Yuri Andropov paid the deserters a visit. Mark remembered his polite manners and exceptional English, the feeling of being inspected. Had the deserters been used? Of course they had. But the process was more complex than exploitation. “They showed us the country,” said Mark, “in the hope that it would make us more supportive of Russia in later years. In my case it worked. I sometimes wonder whether I wasn’t a little brainwashed on that trip.” He wasn’t talking Benzedrine injections and a psychedelic light show, but something subtler. Something that ensured that he never developed an enthusiasm for capitalism and, during his years of exile in Sweden, was always happy to pop into the Soviet Embassy for a chat. Something that put him at odds with America for the rest of his days.

The Soviets did not grant every wish of the deserters but hinted that they might help realize their future plans. Each man was given a pencil and a piece of paper and asked to describe his ideal post-military life. Whitmore and Kmetz looked at a map and plumped for a future in Finland. Kim dreamed of a new life in North Korea. But the six knew that Sweden would be their first port of call, and they were given the name of a helpful contact in Stockholm: Bertil Svahnström, a veteran foreign correspondent and vice chair of the Swedish Committee for Vietnam, an alliance of liberals and Social Democrats opposed to the war in Indochina.

They were also given a friendly warning. “They told us,” said Mark, “to keep our distance from a man named Michael Vale and an organization called the American Deserters Committee.” Vale, said their KGB guide, would try to contact them and gain their confidence.

On May 24, 1968, a fleet of limousines arrived at the Hotel Astoria to drive the deserters to the Leningrad airport, where they each received $300in cash from the Soviet Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee and bear hugs and kisses from their minders.

After an hour staring at the legs of the Swedish cabin crew, the deserters touched down at Stockholm Arlanda Airport to a repeat of the reception that had greeted the Intrepid Four six months before. On that occasion, the waiting photographers had borrowed the iconography of a visiting rock band. Stepping from the plane in identical black suits, John, Craig, Mike, and Rick were framed as the Fab Four of Vietnam War desertion. The Soviets must have seen this, too, and counted it a mistake. The new band of six arrived unscrubbed, unsmartened: authentic members of the counterculture. The Rolling Stones to the Intrepid Four’s Beatles. In the shots from that day, Kim pouts from behind a pair of shades. Mark, in a Red Army fur hat, has a foot perched on his battered suitcase. Whitmore is dragging on a cigarette. Callicoat smiles wryly. Joe Kmetz, a chubby wise guy with a guitar dangling from his right hand, squares off with the camera like a nightclub bouncer. Edwin Arnett hovers at the back, eyes downcast, pale, serious. And, as it would turn out, doomed.

As the Russians had predicted, Bertil Svahnström was the first person to welcome the deserters to Sweden—a friendly, patrician figure happy to be acting as envoy for liberal opposition to the Vietnam War, and to be a conduit for messages from Moscow. But there was little opportunity for private conversation. Reporters and photographers had already swarmed into the arrivals lounge. A press conference was coalescing around the deserters. Reporters fired off questions. Were the men Communists? Had they been influenced by their Russian hosts? Terry Whitmore said the questions were stupid. Joe Kmetz got to his feet and declared that nobody would say a word until the representatives of U.S. press agencies had left the room. “We’ll talk with everybody but Americans,” he insisted. He didn’t trust them. They wrote bullshit and they were probably working for the CIA. The hacks from Associated Press and United Press International had little choice but to withdraw. Svahnström looked quietly pleased at that.

Once the questions had been exhausted, the deserters were whisked into detention by a phalanx of Swedish policemen so courteous that they carried their bags to the waiting cars. Svahnström followed behind in his Volvo. They were taken to a police station in Märsta, a northern suburb of Stockholm—a holding pen for asylum seekers to this day. Here, the men were searched, questioned, given Coke and hot dogs, and permitted to relax in front of the television. They watched a program in which the African American singer Lou Rawls received a rapturous reception from the studio audience. (“At least Sweden ain’t Mississippi,” thought Whitmore.) Although they were told not to smoke in the cells, Joe Kmetz managed to light one of his Russian cigarettes by heating a piece of metal in a plug socket.

Before lights-out, Svahnström came to speak to them. The deserters, he said, would soon be released and issued with permits to remain in Sweden. He could help them negotiate the complexities of the local benefits system, find accommodation and a job. But he also repeated the warning of their Soviet hosts. Recently, Svahnström explained, a group had been established to help fugitive GIs in Sweden. Its representatives would soon be paying them a visit. But the men from the American Deserters Committee, he said, were not to be trusted. They were ideological extremists who would attempt to make the newcomers follow their hard political line.

As the men considered Svahnström’s warning, one of the American news agencies banished from the Arlanda Airport press conference was exacting its revenge. On May 26, UPI sent out a story by Virgil Kret, a correspondent in Tokyo, that was calculated to humiliate the man who had bawled its reporter out of the arrivals lounge.

Kret claimed to have interviewed Joe Kmetz in February, just before Beheiren took the fugitive marine under its wing. The encounter, he said, had taken place in a bar in Tokyo, where Kmetz, drunk and disconsolate, confessed that he’d been hiding for the past sixteen months in the room of a one-eyed Japanese woman ten years his senior, drinking Suntory whisky and cursing his fate.

“He found it difficult to speak, and when he did he spoke English like a Japanese bar girl,” wrote Kret. “He pronounced ‘wife’ as ‘wifu,’ ‘house’ as ‘housu,’ ‘Vietnam’ as ‘Vietnamu.’ ” Kret advised him to get a lawyer and turn himself in. “Never happen!” exclaimed Kmetz. “Never happen! They’ll put me in the monkey housu until I’m an old man!” After this, Kret reported, a member of Beheiren came to collect Kmetz from the bar and take him to a safe house. He was, said the reporter, “the most unhappy and desperate person that I have ever known.”

Was this story true? Was Virgil Kret for real? Apparently so. But the nature of his reality offered a warning about what awaited some of the deserters further down the line. I found his old stories for UPI and the Los Angeles Times and a mention of his presence at a California charity dinner attended by Mr. and Mrs. Zeppo Marx. But an article from an underground newspaper revealed that Kret had been expelled from Japan in 1969, accused of involvement in revolutionary politics. It also noted that in 1975, a source had warned Kret of an imminent assassination attempt on President Gerald Ford. Unfortunately, the source transpired to be God, who issued the tip, Kret claimed, in the form of a “time poem.”

The trail ended with a long-neglected blog called The Obituary of the World, in which Kret explained that he had received telepathic warning of God’s declaration of war against the Earth, and that the Almighty had already supplied the codes that would enable him to launch nuclear revenge upon those who had wounded him most grievously. The Buffalo Bills football team would be among the first to perish. Nothing new had been posted on the site since 2008. Since when, I couldn’t help noticing, the Bills have consistently failed to reach the NFL playoffs.

When the representatives of the American Deserters Committee turned up at the police station, Mark and his comrades were ready to be suspicious. But the men who came to speak with them didn’t seem to be the dangerous figures described by Bertil Svahnström and the KGB. Their manner was friendly and reasonable. They explained that the Swedish welfare system would provide a modest income and that a network of sympathetic Swedes would be only too happy to offer them temporary accommodation. For many of Stockholm’s activist elite—left-leaning actors, journalists, and academics—a deserter in the spare bedroom had become that season’s most fashionable accessory.

Bill Jones, the chairman of the ADC, was a twenty-one-year-old former seminarian from St. Louis, Missouri, who’d deserted from Germany during his training as an army medic. Earnestness seemed his defining quality. Bill explained that he had hoped to meet the deserters in Leningrad, but Svahnström and the Swedish Committee for Vietnam had declined to pay for the ticket.

Bill’s colleague Michael Vale was older and more self-assured. A short, stocky man with a crinkly smile and unironed clothes, Vale was not a deserter but a professional translator from Cincinnati, Ohio, with an address book full of Swedish intellectuals and an apartment in Stockholm where everyone was welcome. Unlike the patrician figure of Svahnström, Vale talked the language of rebellion and revolt. In that moment, it was not clear how profound a revolution he had in mind. Nor was it possible to know that joining the American Deserters Committee would send some of its members to a prison they would never escape.

Copyright © 2018 by Matthew Sweet.

Matthew Sweet is the author of Inventing the Victorians, Shepperton Babylon, and The West End Front. He is a columnist for Art Quarterly and a contributing editor for Newsweek International, and he presents the BBC radio programs Free Thinking, Sound of Cinema, and The Philosopher’s Arms. He was series consultant on the Showtime drama Penny Dreadful and played a moth from the planet Vortis in the BBC2 drama An Adventure in Space and Time. He lives in London.