by Jack Kelly

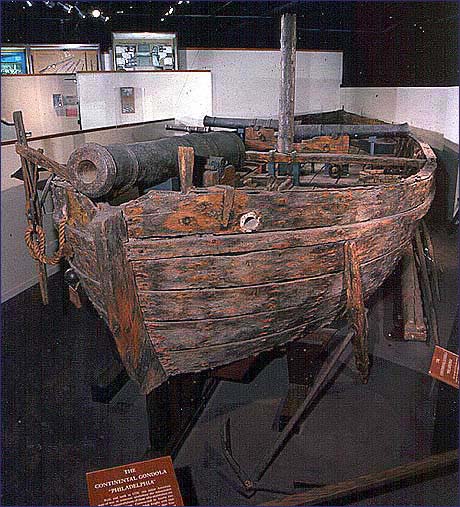

I have traveled to Revolutionary-era battlefields and forts. I’ve examined countless eighteenth-century muskets, uniforms, swords, and shoe buckles. I’ve looked at the original Declaration of Independence in the National Archives. Yet a single artifact has always stood above the others in evoking the immediacy and reality of the Revolutionary War. It rests not under an ornate rotunda but in a dusty corner of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History on the Mall in Washington.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

The Philadelphia is a fifty-five-foot-long wooden boat powered by oars and a single sail that was built in the summer of 1776. Although weathered and battered, the boat has a presence. She is the oldest American warship still in existence. Her record of service goes back to the days, a few months after the nation’s birth, when the success of the Revolution teetered on a knife edge. The forty-five men who manned this cramped open boat played a critical role in making sure that the cause of liberty survived.

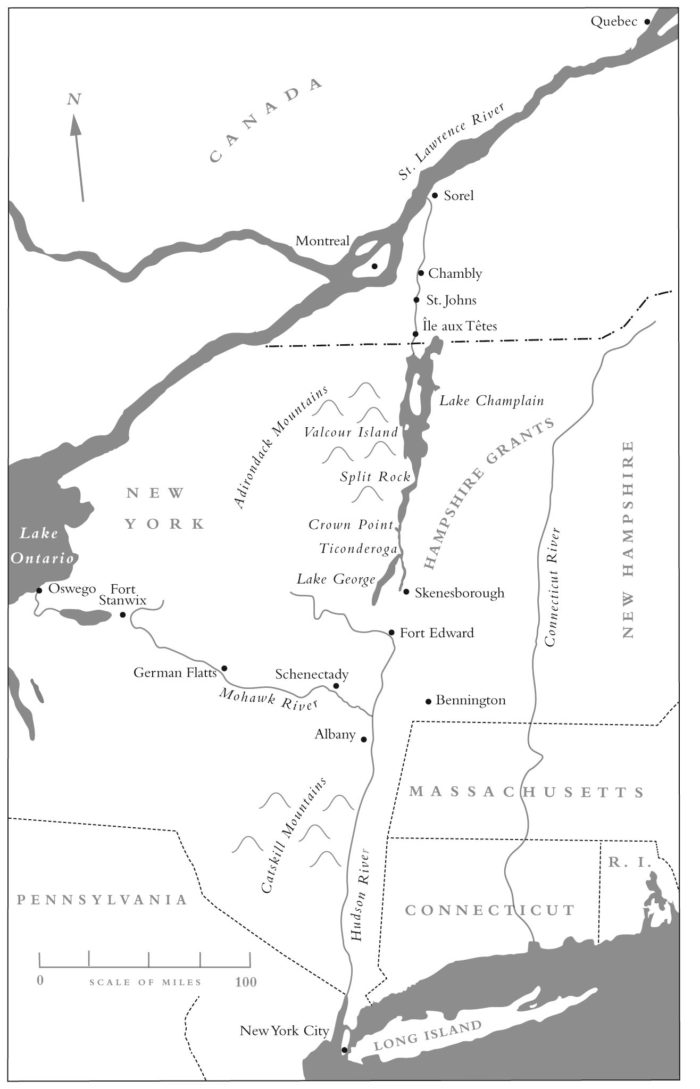

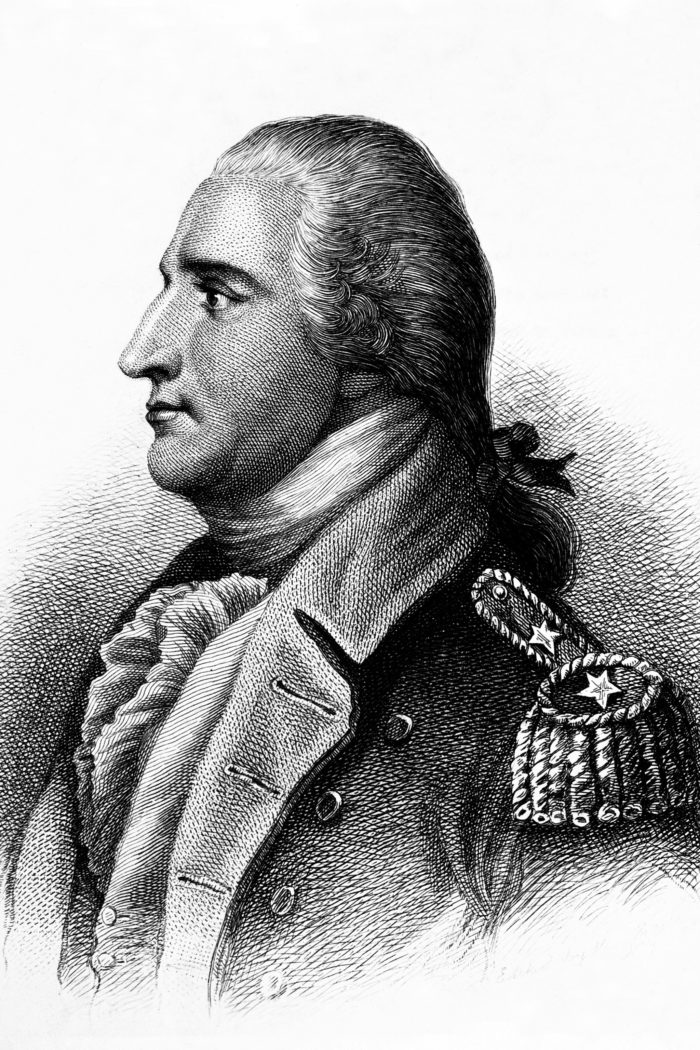

The boat was part of a crucial campaign to head off a British invasion along Lake Champlain in northern New York. Eight gunboats, three larger row galleys, a schooner, and several other vessels were assigned to stop the British from transporting a large army southward along the narrow lake. The American fleet was commanded by Benedict Arnold—he would not turn traitor for another four years.

The summer-long campaign culminated in a series of naval battles. On October 11, Arnold surprised the British by hiding his warships behind Valcour Island, about a mile off the western shore and sixty miles north of the main patriot position at Fort Ticonderoga. A seven-hour cannon duel severely damaged the American vessels, but it gave the enemy pause. A British gunboat blasted a cannonball into the side of the Philadelphia just before the battle ended at dusk. She was one of two American vessels lost in the initial battle. “She Sank About One hour after the engagement was over,” Arnold reported.

That night, Arnold, relying on his extraordinary instinct for military tactics, was able to extricate his fleet from a cul-de-sac and flee south on the lake. A two-day chase ended in a battle farther along the lake. The British captured one American ship. A few boats escaped to Fort Ticonderoga. Arnold ran his remaining vessels aground. He ordered all of them burned to prevent their falling into enemy hands.

The stunned British commander decided to postpone the invasion until the following year. The elimination of the threat from the north and the addition of 600 men from the Fort Ticonderoga garrison encouraged George Washington to cross the Delaware River on Christmas night and defeat the Hessian mercenaries in his daring raid at Trenton.

In 1935, salvage engineer and World War I veteran Lorenzo Hagglund found the Philadelphia in sixty feet of water near the center of Valcour Bay. Her main cannon was still loaded. He raised her that summer and exhibited her locally before donating the boat to the Smithsonian in 1961.

Today, the Philadelphia, her hull planks shrunken, has the aura of one of those aging veterans who turn out on Memorial Day and, however enfeebled, retain a bearing and pride that speaks of their days of service. The Philadelphia has a unique aura of reality about her. These are the guns that men worked 245 years ago. These are the planks that soaked up the blood of her crew. The cannonball that shook and then sank her remains lodged painfully in her hull. These decks are where the struggle for freedom was fought on that day so long ago.

During the battle along the lake, patriots abandoned another gunboat, the Spitfire, which was too badly damaged to go on. Sailors sank her in deep water before scrambling onto other vessels.

In 1997, a survey of the bottom of the lake undertaken by the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum produced a sonar image of a boat resting on the bottom. Divers descended into the murky depths and found the Philadelphia’s sister ship. Mud filled the interior, but her mast, rudder and bow gun were clearly visible.

Raising this wreck will be vastly more complex and expensive than salvaging the Philadelphia. The question is complicated by the appearance in the lake of invasive quagga mussels, which can accelerate the deterioration of an artifact that has survived in cold water for nearly two and a half centuries.

Yet there’s no question that the preservation of these artifacts is worth it. This is our history. These fragile vessels are emblems of the effort and sacrifice on which the edifice of our nation and democracy rest. They should be available for us to contemplate, reminders of a heroism that we can still find in our veins, of a heritage that all of us share.

Jack Kelly is an award-winning author and historian. His books include Band of Giants: The Amateur Soldiers Who Won America’s Independence, which received the DAR History Medal. He is also the author of The Edge of Anarchy, Heaven’s Ditch, and Gunpowder and is a New York Foundation for the Arts fellow in Nonfiction Literature. Kelly has appeared on The History Channel, National Public Radio, and C-Span. He lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.