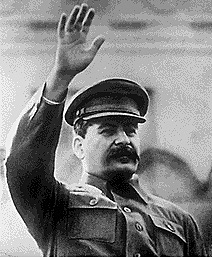

By Catherine Merridale

Order no. 227 was issued on 28 July. At Stalin’s insistence, it was never printed for general distribution. Instead, its contents were conveyed by word of mouth to every man and woman in the army. “Your reports must be pithy, brief, clear, and concrete,” the politruks were told. “There must not be a single person in the armed forces who is not familiar with Comrade Stalin’s order.” In ragged lines, huddled against the sun and wind, the soldiers listened to a roll call of disgrace. “The enemy,” they heard, “has already taken Voroshilovgrad, Starobel’sk, Rossosh’, Kupyansk, Valuiki, Novocherkassk, Rostov-on Don, and half of Voronezh. A section of the troops on the southern front, giving into panic, abandoned Rostov and Novocherkassk without offering any serious defense and without waiting for Moscow’s orders. They covered their colors in shame.” The leader then spelled out what every soldier knew, which was that the civilian population, their own people, had lost almost all faith in them. The time had come to stand their ground whatever the cost. As Stalin’s order put it, “Every officer, every soldier and political worker must understand that our resources are not limitless. The territory of the Soviet state is not just desert, it is people—workers, peasants, intellectuals, our fathers, mothers, wives, brothers, and children.” Even Stalin conceded that at least seventy million of these were now behind the German lines.

Stalin’s remedy was embodied in a new slogan. “Not a step back!” was to become the army’s watchword. Every man was told to fight until his final drop of blood. “Are there any extenuating causes for withdrawing from a firing position?” soldiers would ask their politruks. In future, the reply that handbooks prescribed would be “The only extenuating cause is death.” “Panicmongers and cowards,” Stalin decreed, “must be destroyed on the spot.” An officer who permitted his men to retreat without explicit orders was now to be arrested on a capital charge. And all personnel were confronted with a new sanction. The guardhouse was too comfortable to be used for criminals; in future, laggards, cowards, defeatists, and other miscreants would be consigned to penal battalions.

There, they would have an opportunity “to atone for their crimes against the motherland with their own blood.” In other words, they would be assigned the most hazardous tasks, including suicidal assaults and missions deep behind the German lines. For this last chance, they were supposed to feel gratitude. Only through death (or certain specified kinds of life threatening injury) could outcasts redeem their names, saving their families and restoring their honor before the Soviet people. Meanwhile, to help the others concentrate, the new rules called for units of regular troops to be stationed behind the front line. These “blocking units” were to supplement existing zagradotryady, the NKVD troops whose task had always been to guard the rear. Their orders were to kill anyone who lagged behind or attempted to run away.

Order no. 227 was not made public until 1988, when it was printed as part of the policy of glasnost, or openness. More than forty years after the end of the war, the measure sounded cruel to people reared on the romantic epic of Soviet victory. A generation that had grown up in decades of peace balked at the old state’s lack of pity. But in 1942 most soldiers would have recognized the decree as a restatement of current rules. Deserters and cowards had always been in line for a bullet, with or without benefit of tribunal. Since 1941, their families, too, had suffered their disgrace. Like a slap in the face, the new order was intended to remind the men, to call them to account. And their response was frequently relief. “It was a necessary and important step,” Lev Lvovich told me. “We all knew where we stood after we had heard it. And we all—it’s true—felt better. Yes, we felt better.” “We have read Stalin’s order no. 227,” Moskvin wrote in his diary on 22 August. “He openly recognizes the catastrophic situation in the south. My head is full of one idea: who is guilty over this? Yesterday they told us about the fall of Maikop, today Krasnodar. The political information boys keep asking if there isn’t some treachery at work in all this. I think so, too. But at least Stalin is on our side! . . . So, not a step back! It’s timely and it’s just.”

To the south, where the retreat Moskvin abhorred was taking place, news of the order chilled the blood of depressed, tired men. “As the divisional commander read it,” a military correspondent wrote, “the people stood rigid. It made our skin crawl.” It was one thing to insist on sacrifice but quite another to be making it. But even then, all that the men were hearing was a repetition of familiar rules. Few soldiers, by this stage in the war, would not have heard about or seen at least one summary execution, the laggard or deserter drawn aside and shot without reflection or remorse. The numbers are hard to establish, since tribunals were seldom involved. It is estimated that about 158,000 men were formally sentenced to be executed during the war. But the figure does not include the thousands whose lives ended in roadside dust, the stressed and shattered conscripts shot as “betrayers of the motherland”; nor does it include the thousands more shot for retreating—or even for seeming to retreat—as battle loomed. At Stalingrad, as many as 13,500 men are thought to have been shot in the space of a few weeks.

“We shot the men who tried to mutilate themselves,” a military lawyer said. “They weren’t worth anything, and if we sent them to prison we were only giving them what they wanted.” It was helpful to have a better use for able-bodied men—that much was a real outcome of Stalin’s order. Copied from German units that the Soviets observed in 1941, the first penal battalions were ready well in time for Stalingrad. Though most assignments in this war were dangerous, those in the shtraf units were wretched, one step removed from the dog’s death that awaited deserters and common crooks. “We thought it would be better than a prison camp,” Ivan Gorin, who survived a penal battalion, explained. “We didn’t realize at the time that it was just a death sentence.” Penal battalions, in which at least 422,700 men eventually served, were forlorn, deadly, soul destroying. But there could not have been a soldier anywhere who doubted that in this army, in any role, his life was cheap.

Though Stalin’s order formalized existing regulations, the process of its implementation exposed a fundamental problem of mentalities. Indeed, its reception in many quarters was symptomatic of the very weakness that it was supposed to remedy. People brought up in a culture of denunciations and show trials were used to blaming others when disaster struck. It was natural for Soviet troops to hear Stalin’s words as yet another move against identifiable—and other—anti-Soviet or unmanly minorities. The new slogan was treated, initially at least, like any other sinister attack on enemies within. Political officers read the order to their men but acted, as some inspectors observed, as if it “related solely to soldiers at the front. . . . Carelessness and complacency are the rule . . . and officers and political workers . . . take a liberal attitude to breaches of discipline such as drunkenness, desertion, and self-mutilation.” The warm summer nights seemed to encourage laxity. In August, the month after Stalin’s order, the number of breaches of discipline continued to increase.

Obligatory repetition turned the leader’s words to cliché. The new instructions, once ignored, could sound as stale, if not as benign, as orders to eat more carrots or be vigilant for lice. The message was drummed into every soldier’s head for weeks. Some hack in Moscow composed pages of doggerel verse to ram it home. Inelegant in the first place, it loses nothing in translation. “Not a step back!” it rattles. “It’s a matter of honor to fulfill the military order. For all who waver, death on the spot. There’s no place for cowards among us.” Groups of soldiers, weary of government lies, were always quick to identify hypocrisy, and that autumn they watched their commanders evading the new rules.

Few officers were keen to spare their best men for service in the blocking units. They had been in the field too long; they knew the value of a man who handled weapons well. So the new formations were stuffed with individuals who could not fight, including invalids, the simpleminded, and—of course—officers’ special friends. Instead of aiming rifles at men’s backs, these people’s duties soon included valeting staff uniforms or cleaning the latrines. In October 1942, the idea of regular blocking units at the front (as opposed to the autonomous forces of the NKVD) was quietly dropped.

Meanwhile, the retreat that had provoked the order in July continued in the south. German troops took another eight hundred kilometers of Soviet soil on their way to the Caucasus. The defense of their Caspian oil that autumn cost the Red Army another 200,000 lives. As late as September, army inspectors would observe that “military discipline is low, and order no. 227 is not being carried out by all soldiers and officers.” It was not mere coercion that changed the fortunes of the Red Army that autumn. Instead, even in the depth of their crisis, soldiers appeared to find a new resolve. It was as if despair itself—or rather, the effort of one final stand—could wake men from the torpor of defeat. Their new mood was connected to a dawning sense of professionalism, a consciousness of skill and competence that the leaders had started to encourage. For years, Stalin’s regime had herded people like sheep, despising individuality and punishing initiative. Now, slowly, even reluctantly, it found itself presiding over the emergence of a corps of able, self-reliant fighters. The process would take months, gathering pace in1943. But rage and hatred were at last translating into clear, cold plans.

Excerpted from Ivan’s War: Life and Death in the Red Army, 1939-1945 by Catherine Merridale.

Copyright © 2006 by the author and reprinted by permission of Picador, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

CATHERINE MERRIDALE is the author of the critically acclaimed Night of Stone, winner of Britain’s Heinemann Award for Literature, and Ivan’t War. A professor of contemporary history at the University of London, she also writes for the London Review of Books, the New Statesman, and The Independent and regularly presents history features for the BBC.