by Anne Sebba

On 6 June 1944 Allied forces began the long-awaited invasion of northern France. Operation Overlord, code-name for the Normandy landings, was the largest seaborne invasion in history. British, American and Canadian forces landed on a fifty-mile stretch of coast. Fighting was intense, casualties high and progress slower than the Allies had hoped. The town of Caen, a major objective, was not captured until 21 July. The Allies could not break out beyond Bayeux until 1 August. But, as they advanced towards Paris, many towns saw spontaneous demonstrations of support from the local people. The vast majority of them women, often wearing red, white and blue and kissing every soldier in sight.

The battle for Paris itself began on 15 August. Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy was the commander of the Paris Region FFI (Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur), the umbrella network for the military resistance. He led the popular uprising in the city as the police went on strike and the Métro closed. Cécile Rol-Tanguy, the young activist married to Henri, knew in advance that this was the moment. Remembering frantically typing out propaganda posters calling for insurrection which needed circulating across the city.

Cécile Rol-Tanguy Struggles with the Resistance

The patriotic French – ‘all men from 18 to 50 able to carry a weapon’ – were urged to join ‘the struggle against the invader’. Promising ‘victory was near’ and ‘chastisement for the traitors’, the Vichy loyalists. The Rol-Tanguys, both committed communists, had managed to survive in occupied Paris for four years leading a dangerous and clandestine existence. Taking enormous risks while bringing up a young family. They were fortunate not to be arrested, like so many of their fellow fighters. Although Cécile Rol-Tanguy worked as Henri’s liaison officer, they could not live together as he was a wanted man. Far too well known by the Germans.

In 1942 Cécile Rol-Tanguy’s father, François, had been arrested for a second time. This time deported to Auschwitz where he was killed, and the following year Cécile gave birth to a son, Jean. So Cécile Rol-Tanguy and her mother now lived together in a tiny studio with the two children, Hélène, born in May 1941, and baby Jean, struggling to find enough to eat. She remembers being so thin at one point that her culottes fell down.

Cécile Rol-Tanguy had to traverse the city for her work. She sometimes carried Hélène in her arms while hiding weapons in a sack of potatoes which she pushed in the pram. At other times she buried papers underneath the pram bedding, with the baby on top. She had a number of aliases, Jeanne, Yvette and Lucie, and occasionally changed her hairstyle or wore a fashionable turban. But she did little otherwise to disguise herself. Afterwards, she always made light of her activities, claiming she had done nothing special. ‘My strength was always in remaining cool. I think that was my character.’

Dietrich von Choltitz Signs the Surrender of Paris

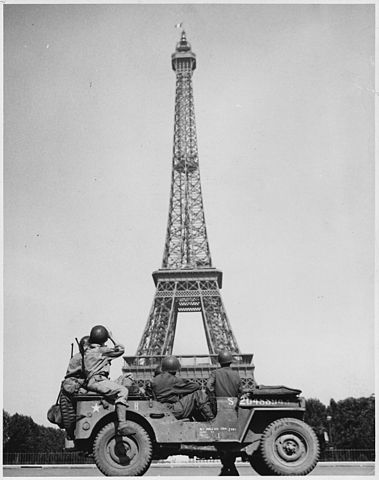

It required all her strength to stay cool during these exceptionally bloody and chaotic eleven days. Almost 1,500 Parisians died in the struggle to chase out 20,000 occupying soldiers. Collaborationist snipers, many of whom were Vichy miliciens, firing from rooftops wherever they could. Suddenly rosette merchants appeared on the streets. They hoped to make a quick franc or two from women determined to declare their allegiance to the nation. By sporting a tricolore rosette in their blouse. At last, on 25 August, Dietrich von Choltitz, the German Military Governor of Paris, emerged from his headquarters in the Hôtel Meurice. He was ready to sign the surrender documents.

Henri Rol-Tanguy and General Philippe Leclerc of the 2nd Armoured Division, de Gaulle’s representative, were also signatories. The following day de Gaulle, unmissable thanks to his immense height, made his triumphal walk down the Champs-Elysées with thousands of people shouting ‘Vive de Gaulle!’ As he walked, he raised his long arms towards the sky. Turning first left and then right, as if offering thanks. A gesture that was to become his hallmark but was completely new to Parisians then.

‘For those gathered there,’ remarked Elisabeth Meynard, ‘he was the living symbol of resistance to the enemy invader.’ With the odd German or milicien sniper taking murderous pot-shots, he then delivered a rousing speech. First referring to ‘Paris liberated by her own people…supported by the whole of France’.

Marie Dalmaso’s Bravery Goes Unrecognized

But he could not totally deny the contribution made by the brave communist fighters among whom Cécile Rol-Tanguy had played an important role. It was a crucial factor in determining the political future of the country. One of the liveliest post-war arguments has centered on the part played by female resisters. Whether women carried weapons or ‘merely’ acted in support. Clearly, in Paris women under the command of Rol-Tanguy did use weapons. As can be seen in contemporary footage of the Liberation. It shows young girls such as the twenty-two-year-old Anne Marie Dalmaso handling a gun as she fights in the action to defend the Hôtel de Ville.

Dalmaso had joined the teams of young volunteers especially created to help those affected by the bombing. Madeleine Riffaud, a twenty-year-old communist arrested in July for shooting and killing a German officer in daylight on a bridge overlooking the Seine, was interrogated in Fresnes. She even had a date set for her execution. But was released in a prisoner exchange and returned to fight in the resistance.

On the day after the Liberation Frida Wattenberg, only nineteen, a Paris-born resister working for the OSE and other groups, was immediately sent to the Toulouse office for ‘Questions Juives’. Retrieving crucial files that would contain details of any Jewish genocide in France. ‘When the official asked me what authority I had to claim them I replied: “All I have is my gun,” and pointed it at him.’ Marie-France Geoffroy-Dechaume, cycled around the Normandy coast with explosives at the ready. She handled not only weapons but also bomb-making equipment.

The Brutality of the Reprisals was Shocking

However, in the euphoria of liberation, the abiding image is of women throughout France was termed collaboration horizontale. Those accused, rightly or wrongly, of having slept with a German, sometimes but not always in exchange for benefits. Having collaborated by providing sensitive information or merely of having serviced the occupier in the role of housekeeper, seamstress or cook, were all seen as women guilty of infidelity to the nation. They were denounced, hectored, brought to their knees, had their heads shaved. Some even had swastikas drawn or branded on their bodies and were made to parade half naked through town to display their shame publicly.

No one who watched ever forgot the barbarity. As whole villages turned out to cheer young girls being humiliated perhaps for no greater crime than sleeping with a German in return for some silk stockings or a little bit of money.

Lee Miller, the US-born photographer and fashion model who had been accredited as a war reporter with British Vogue, had flown over to France on 2 August. She was making her way up to Paris. ‘I won’t be the first woman journalist in Paris… but I’ll be the first dame photographer. I think, unless someone parachutes in’. Miller was shocked to witness the ‘chastisement’ of two girls who were shaved, spat on and publicly slapped even though their interrogation. Some had merely confirmed that there was enough evidence for a subsequent trial. ‘They were stupid little girls not intelligent enough to feel ashamed,’ Lee wrote to her editor, Audrey Withers. It was a sickeningly misogynistic response.

Max and Madeleine Goa

The women – by some estimates as many as 20,000, known to history as les tondues, or shaven ones – were punished by the men who had failed to defend them. One of them was Lisette, the French secretary whose long-standing affair with Johann. A married German soldier, was known of by many in her circle. Her pro-German parents, concierges who were helping themselves to clothes in the apartment of a deported Jewish couple, may have supported her. But her own cousins refused to speak to her. She was lucky not to have had further humiliation in the form of branding inflicted on her as payment for the luxuries she had received during the war. But at the same time de Gaulle did not punish the male political or commercial elite who had backed Pétain. Seeing them as valuable allies in the fight against communism.

The épuration sauvage

The controversy has gathered momentum in the intervening years as historians have pointed out how much of the punishment was not only gender-based, but a question of class and ancient score-settling. In the terror of the moment there were tragic mistakes. Max and Madeleine Goa, two young resisters who, having sheltered evading airmen, were celebrating victory on the balcony of their apartment in the Avenue d’Italie when shots were fired. The mob below was convinced they had come from them. So the pair were hauled down to the street below where Max was lynched. Then run over by a tank. Madeleine taken away to a prison, locked up until she went mad, and then murdered.

Of course there were articulate and fierce opponents of the épuration sauvage. The wave of vicious punishments without trial, including executions as well as humiliation, that now swept through France. These included men such as Henri Rol-Tanguy and the communist surrealist poet. Also Paul Eluard both married to women who had risked their lives to resist.

‘They had not sold France and they often had not sold anything at all.’

Eluard, in his 1944 poem ‘Comprenne qui voudra’ (Understand if you will), expressed powerfully his disgust at how, in order not to punish the real culprits. The mob had attacked defenseless girls who were trembling with fear as they lay with torn dresses. While the crowd laughed and parents held up children to see better. Many of whom simply did not understand what was happening to the girls nor why. Angered by the sight of a beautiful woman’s hair lying on the pavement in front of a barber’s shop in Rue de Grenelle. Eluard pointed out that they had not, in any case, harmed anyone else. ‘They had not sold France and they often had not sold anything at all.’

ANNE SEBBA is a biographer, lecturer, and former Reuters foreign correspondent who has written several books and is a member of the Society of Authors Executive Committee. She lives in London.