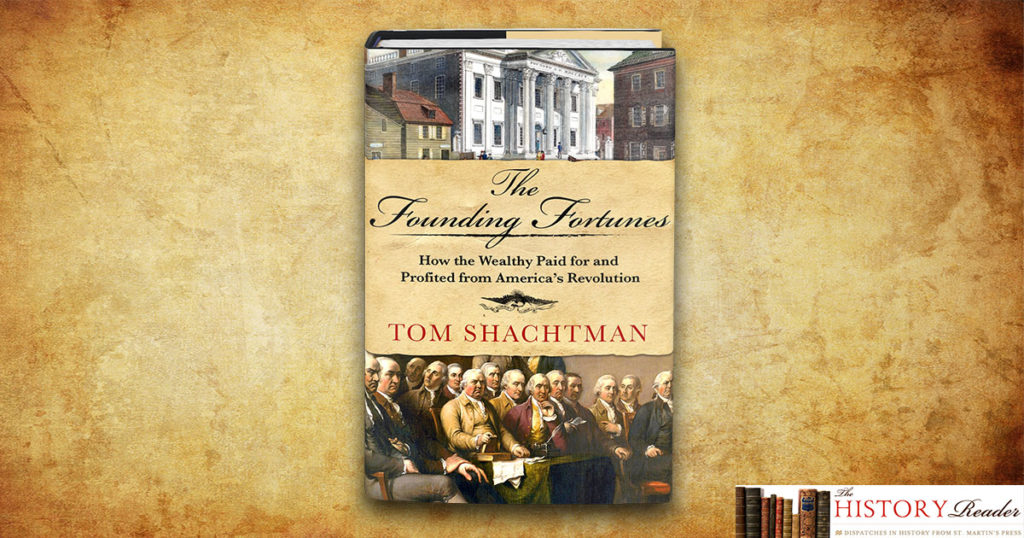

by Tom Shachtman

In The Founding Fortunes, historian Tom Shachtman reveals the ways in which a dozen notable Revolutionaries deeply affected the finances and birth of the new country while making and losing their fortunes. Check out an exclusive excerpt here.

Throughout his life Benjamin Franklin had a knack for fortuitous timing. The prime exemplar of the American rags-to-riches story, then sixty-eight, arrived home to Philadelphia just after Lexington and Concord, in time to be appointed a delegate to the spring 1775 Continental Congress. Until a year ago he had shared with most of his peers the belief that the colonies must remain within the Empire. For more than a decade in London he had worked toward that end, until pilloried in front of an audience of MPs. Their refusals to accede to any suggestions for reconciliation with the colonists forced him to conclude that America must break with the mother country.

The majority of his fellow delegates in Philadelphia had not yet reached that point, but the American bloodshed at Lexington and Concord had convinced more of them that doing nothing to halt the British would bring increasing indignities and an eventual loss of their honor as well as their fortunes. Those who recognized that the only alternative to submission was independence were still in the minority, but they, as well as all the others, accepted the need for more active resistance to Great Britain, and plunged into the tasks of defending America: summoning an army and deciding how to pay for it.

Order Your Personalized Signed Copy Now from Oblong Books!

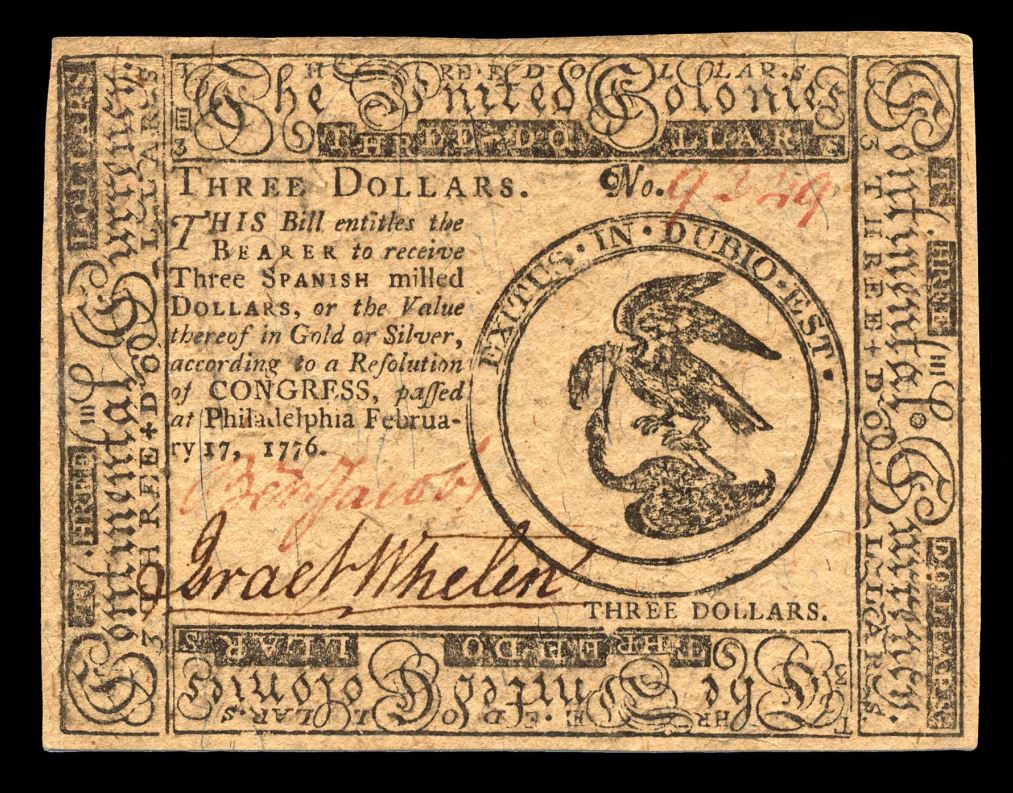

American mythology has glossed over their decision to finance the war. Even at the time there was remarkably little discussion of it: Taxation being the bone of contention with Great Britain, not for an instant did the delegates consider direct taxes to finance the war; and anyway, Congress had not been specifically granted the power to tax American citizens. Options for obtaining money for the war had been further narrowed by the absence of a national bank. While in 1694 Great Britain had established the Bank of England primarily to finance wars in exchange for first call on future British tax receipts, in America there were no banks and no federal tax receipts to promise. So the delegates adopted the financing method used by provincial legislatures, the printing of money, known as making an emission. They authorized a two-million-dollar one; by fall they would approve another six million, and before the end of 1776 a total of twenty-five million.

They could not guarantee the value of the currency in which these emissions were made, even though the Continental dollar certificates said that they were redeemable for gold or silver, because without actual future tax receipts, the value of the paper currency would vary according to the whim of the market. To back the Continental dollar, the Continental Congress could only hope that the colonies would honor their pledges to pay into the central government on a regular basis, enabling the central government to sink (redeem) the new currency—as individual colonies had done in the past with their own emissions. The delegates decreed a four-year payment schedule, based on each colony’s percentage of the overall population. They believed that the thirteen colonies would not have much difficulty in meeting the schedule since the amounts requested would be less, per capita, than what the colonies had recently been collecting in taxes. Hancock, Washington, and a few other wealthy delegates supplemented the first emissions by themselves paying to outfit soldiers, although they knew that repayment might well have to wait until war’s end.

There was similarly not much discussion on choosing a commander in chief. While Hancock thought he was perfect for the job, those who knew him best did not. His dismay was visible as John Adams nominated Washington—a French and Indian War veteran and colonial legislator who had recently raised and outfitted a thousand troops—and as Sam Adams then seconded his cousin’s motion, which carried easily. Thereafter Hancock had little to do with the Adamses; instead, a biographer writes, he “developed increasingly warm friendships with Southerners, who like him were wealthy, well-educated, cultured men who appreciated fine clothes, foods, wines, and other luxuries.”

Part of Washington’s attractiveness to Congress lay in his presumptive immunity to bribery due to his significant wealth. They had all heard how Washington’s British military-leader counterparts enriched themselves through their service or by accepting rewards after it, and they did not want that to happen in America. An equal part of Washington’s appeal for Congress lay in his extraordinary willingness to abide by republican ideals and to subsume his authority to civilian control. He raised no objections when Congress chose his subordinates, one general from each colony. Two were fellow wealthy delegates, John Sullivan of New Hampshire and Philip Schuyler of New York. In June 1775 Washington traveled with them, and with rifle companies from Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, toward Boston, to take over the command.

While Congress had been meeting, several generals had arrived in Boston from Great Britain, accompanied by more troops and bearing cash for those already there. These new officers had previously served in America, and their leader, William Howe, as an MP had opposed the Coercive Acts as counterproductive; he was returning to America only at the personal request of King George III. Howe and his colleagues hatched a plan to break the British troops out of rebel encirclement. But their plan was based on the assumption that the rebels did not possess the discipline to withstand a coordinated frontal assault by seasoned Redcoats. On June 17, 1775, while Washington was still in transit, the British charged the most heavily defended rebel points, Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill. They eventually took both hills but suffered twice as many casualties as the defenders, and had a third of their men wounded—and then did not pursue the rebels. For allowing that, General Gage was recalled to London. Among the American dead was military leader Joseph Warren, author of the “Suffolk Resolves.”

Tom Shachtman has written or co-authored more than 35 books, as well as documentaries for ABC, CBS, NBC, PBS, and BBC, and has taught at New York University and lectured at Harvard, Stanford, Georgia Tech, the Smithsonian, and the Library of Congress. He is a former chairman of The Writers Room in Manhattan, a trustee of the Connecticut Humanities Council, a founding director of the Upper Housatonic Valley National Heritage Area, and an occasional columnist for the Lakeville Journal of Northwest Connecticut.