by David Gibbins

Almost half of the ships that I cover in my book, A History of the World in 12 Shipwrecks, are vessels of war—a Viking longship, King Henry VIII’s flagship the Mary Rose, a frigate of the 18th century, Sir John Franklin’s HMS Terror from his doomed Arctic expedition, and an armed merchantman of the Second World War. The wrecks of warships have a special significance because they are often associated with events in which our very survival has been at stake. The people who died in them were often volunteers from all walks of life who answered the call—often, too, people with whom we have a direct connection through our own family histories.

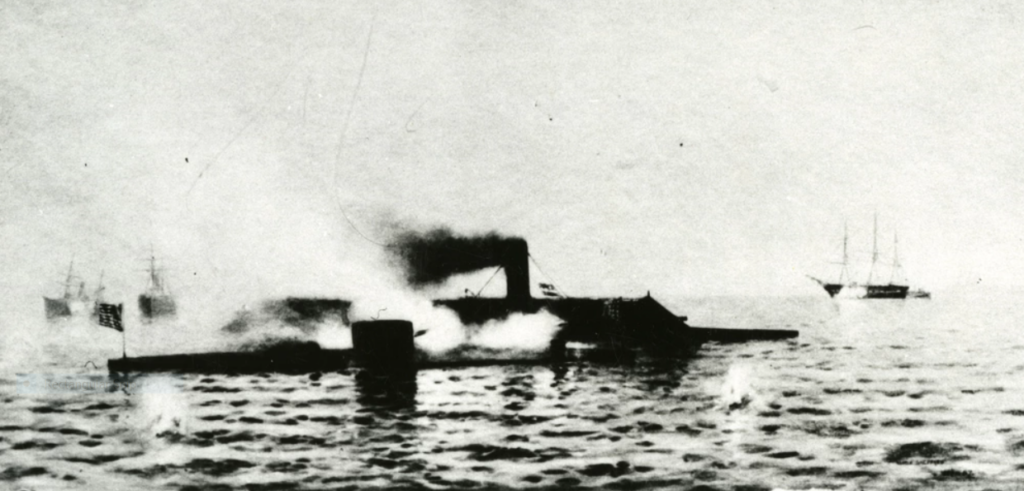

The wrecks at Pearl Harbor from the Japanese attack of December 7, 1941, are among the most emotive of these sites because they are war graves and monuments to one of the most decisive events in American history. Among wrecks from earlier wars that have been investigated archaeologically, there are few more significant than the ironclad USS Monitor from the Civil War. Built under orders from President Lincoln to a revolutionary new design, she was the first ‘turret’ ship in the US Navy and the predecessor of the battleships to come, including those lost in Pearl Harbor. Earlier ships had to turn to bring their guns to bear on an enemy; the turret meant that the guns could be aimed independently from the ship’s movements, allowing much greater versatility in attack.

The Civil War was not only a formative event in US history but a watershed period in technology and design, with the Industrial Revolution harnessed to the needs of war and drawing on the ingenuity of inventors at the time. The day before the Monitor met the Confederate ironclad Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862, the Virginia destroyed two of the old-fashioned wooden warships of the Union Navy, whose guns had little effect on Virginia’s hull. The clash between the two ironclads was a draw but rendered wooden warships obsolete and paved the way for an ‘arms race’ in warship production. Over the following half-century, deterrence and standoff were as much a strategy as active engagement with the enemy.

The wreck of the Monitor was discovered in 1973 some 16 miles off Cape Hatteras, where she had been lost in a storm while being towed south to join the blockade of Confederate ports. The site was designated as a National Marine Sanctuary in 1975 and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration was mandated to protect the wreck. Under their oversight numerous artifacts have been raised, conserved in a state-of-the-art facility and displayed in the Mariners’ Museum at Newport News, one of the premier museums for wreck finds anywhere in the world.

The crew who died in the wreck were a cross-section of American society at the time—five of the enlisted men had been born in Britain or Ireland, and three were African-American. The accounts of survivors picked up by the towing vessel paint a vivid picture of the moment of loss. “Dear wife,” wrote one, “… we had 16 poor fellows drownded. I can tell you I thank God my life is spaired (sic).” A red signal lantern in the darkness that was the last they saw of Monitor was also the first artifact recovered from the wreck in 1977. Among the other items were silver cutlery bearing the names of several of the officers who died, and in the gun turret, divers discovered the skeletal remains of two men who had not made it out in time. The burial of those men in Arlington Cemetery in 2013 means that they have been accorded the same respect as those who died in later wars and helps to ensure that Monitor and her role in history will not be forgotten.

David Gibbins is the internationally bestselling author of the Jack Howard novels, which have sold over three million copies worldwide and are published in thirty languages, and the Total War series of historical novels.

Gibbins has worked in underwater archaeology all his professional life. After taking a PhD from Cambridge University he taught archaeology in Britain and abroad, and is a world authority on ancient shipwrecks and sunken cities. He has led numerous expeditions to investigate underwater sites in the Mediterranean and around the world. He currently divides his time between fieldwork, England and Canada.